Who should President Trump nominate to the Supreme Court? The answer to this question is both legal and political. Conservative legal scholars want Trump to choose an originalist. But do the American people value those same ideals? In large part, the answer seems to be yes.

We recently performed a national conjoint experiment in a working paper to examine which judicial philosophies and nominee characteristics most appeal to the American public. Do the American people want presidents to elevate sitting circuit court judges to the High Court? Do they prefer nominees from Ivy League law schools or nominees who hold certain legal views? We asked 1,000 adult respondents (using YouGov) to answer these questions.

For background, we provided each of our 1,000 respondents five pairs of possible (but fictional) nominees with randomly assigned attributes. The attributes included the nominees’ age, race, sex, judicial philosophy, professional background, religion, law school, perceived ideology, American Bar Association rating, whether the nominee ever held elective office, and the party of the appointing president.

Respondents saw the description (but no pictures) of two potential nominees and then selected one of the two. A respondent might choose between, on the one hand, a white male circuit court judge who believes in the role of precedent, and a white female law professor who believes in legal pragmatism on the other. Another respondent might choose between a black female government attorney who believes in using foreign law, and a Hispanic male attorney in private practice who believes in original meaning. The combinations were nearly limitless. By varying these attributes across a large sample of respondents, the conjoint experiment allowed us to determine which attributes respondents most prefer.

We weighted survey responses by matching respondents’ 2016 presidential vote choice, gender, age, race, and education with the U.S. general population (according to the American Community Survey).

The results suggest that the people on Trump’s shortlist will all generate significant support, but some will enjoy more support than others.

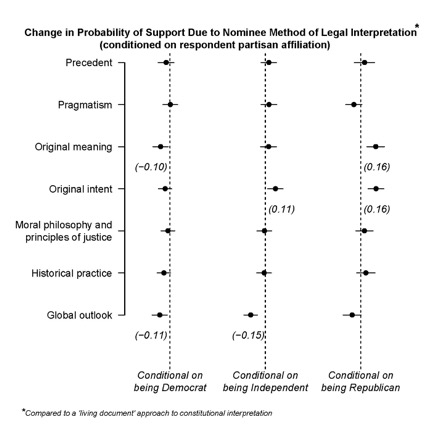

Looking first at judicial philosophy, the data show that the American people tend to support nominees who espouse “Original Intent,” which we defined as judges who “look to the intent of the drafters and ratifiers of the Constitution to reach conclusions about its meaning.” As the figure below shows, independents and Republicans strongly preferred such nominees to those who espoused a “Living Constitution” approach, which we defined as judges who “look to the evolving views and values of the American public when interpreting the Constitution.” (For an example of interpreting the data on the graph, it can be read that Republicans were 16 percent more likely to prefer a nominee who espouses “Original Intent” over one who believes in a “Living Constitution.”)

It’s worth pointing out that Democrats and Republicans clearly divide over nominees who pursue “Original Meaning,” which we defined as a judge who “considers what the words in the Constitution meant at the time those words were crafted.” Perhaps the division turns on the fact that this perspective has been tied most closely to the late Justice Scalia. Whatever the cause, it is clear that Republicans support an Original Meaning approach while Democrats oppose it (relative to the Living Constitution approach).

What’s also clear is that all Americans hold a dim view of internationalist judges with a global outlook, who “look to how public officials in other countries have interpreted similar words or phrases.” Democrats, independents, and Republicans all dislike such methods. (The “Global Outlook” variable is negative but not statistically significant for Republican respondents because they already dislike the Living Constitution approach—the baseline comparison philosophy—so much.)

We also separately examined respondents who voted for Trump and those who voted for Clinton. The two groups share much in common, but their differences are telling. Whereas Trump voters do not prefer nominees of one sex to another, Clinton voters significantly prefer female nominees to male nominees. Next, Trump voters do not favor nominees with judicial or academic backgrounds while Clinton voters significantly prefer law professors and federal appellate judges. Contrary to conventional belief, neither Trump nor Clinton voters prefer Ivy League educated nominees to nominees who went to other law schools.

What do these results mean politically for the eventual nominee? First, as we stated above, Trump’s shortlisters all seem to have characteristics that Republicans and independents support—a testament to the quality of the initial shortlist selection process.

Second, it is clear that a nominee whose judicial philosophy pursues original intent is likely to get the most initial support from independents and Republicans. Whoever gets the nod, that nominee will get the most immediate support by highlighting his or her reliance on original intent.

Third, if he desires, Trump could reduce political opposition if he selects a sitting appellate court judge, a law professor, or a woman—or someone who is all three. Democrats prefer those characteristics. Conditional on the nominee having a strong conservative judicial philosophy, selecting someone who meets these criteria could beat back political opposition. To be sure, given their strong signals to date, Democrats are unlikely to vote for any of Trump’s nominees. But selecting a sitting judge, law professor, or woman could inoculate the nominee against some opposition—at least at the margins, where it seems all politics regrettably exists these days.

Trump and his supporters want a rock-ribbed conservative to fill the vacancy (just as liberals would have demanded a fervent liberal if the election had gone the other way). Assuming he selects an originalist, which he is likely to do, Republicans and independents will be happy. Whether his selection satisfies anyone on the left remains to be seen.