The day after the 2014 election, Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell was asked what kind of proposals his new majority could work on with President Obama. “Trade agreements,” McConnell said, adding, “The President and I were just talking about that before I came over here.”

And when Obama called on Congress during his State of the Union speech this month to pass legislation supporting new trade agreements, it was one of the few subjects that did not raise Republican ire. It did not meet with much enthusiasm from Obama’s fellow Democrats, however, who lined up to pan the president’s proposal to push the trade agenda forward. No problem, said a White House aide several days later, the President will “steamroll” them.

The politics of trade have long broken down along fairly strict partisan lines; pro-business Republicans are for trade and pro-labor Democrats are against it. Freed from narrow constituent politics, however, Democrats in the White House have pushed for greater openness to trade, largely because expanding trade is a necessarily an important part of the foreign policy agenda of any president interested in maintaining the United States’ global leadership. President Clinton famously passed the North American Free Trade Agreement and permanent normal trade relations with China. So it isn’t surprising that Obama views new trade deals as central to his foreign policy legacy.

Still, getting new trade agreements through Congress is tough sledding for presidents of any party. Populist demagoguing and popular myth still hold that trade kills American jobs. Many voters of all stripes believe this. Butressing America’s international leadership makes for far less compelling images than those of shuttered factories that have lost their competitive edge to job-stealing firms on the other side of the planet. The misery of the few who lose out in the shuffle of trade liberalization has huge political resonance, even if the overall economic benefit to Americans significantly outweighs the detriment.

The policy landscape is littered with competing studies that demonstrate the success or failure of trade agreements. Depending on who you believe, NAFTA has cost or delivered millions of jobs. Permanently normalized trade relations for China resulted in the greatest and worst transfer of wealth in human history, unless actually it didn’t. The obvious reality is that trade liberalization produces some losers, even if the rest of us are winners. But stories about the collapse of American manufacturing and televised portraits of out-of-work breadwinners make for more sympathetic news stories than the fact that a new trade deal has added a few hundred dollars to the purchasing power of the average family.

The way policymakers talk about trade is often disingenuous. Trade agreements these days are about reducing barriers to trade in a supply chain that can wend through many countries. They are about standardizing approaches to information gathering and policy making. They set rules for economic governance that limit discrimination and encourage greater opportunities for an increased number and kind of enterprises in the economy. And importantly, they set the rules for trade in services, which is the forgotten giant in international trade.

This is all wonky stuff, so when forced to talk about trade without putting its audience to sleep, the administration finds itself reverting to simplification. When in doubt, Obama and the administration, like previous Republican and Democratic administrations, talk about how trade agreements are about exports, as the president did when he proposed in his 2010 State of the Union speech to double U.S. exports in five years. We didn’t come close, but it was a worthy aspiration.

The global economy and the role of the United States in that economy has changed dramatically since the 1950s, but the politics of trade is still very much grounded in that long-ago epoch. Back then, you made a finished product in one country and sold it to another. The way trade data is gathered still assumes a 1950s approach; the country in which a product’s assembly is finalized gets full credit for the value of that product. So China gets full credit for the value of an iPhone it assembles from component parts made in other countries, including the lion’s share of the value that iPhone represents: its design, which really never left Cupertino, Calif.

The enduring, alluring image of the “good (manufacturing) job at good wages” from the days in the 1950s in which manufacturing employed 60 percent of American workers, is tough to shake in the public and political consciousness. Despite the fact that fewer than 10 percent of Americans work in manufacturing and that America’s role in international trade is increasingly focused on design and technological development, and providing services, the iconic assembly line worker is the poster child for U.S. trade policy.

He or she isn’t doing as well these days.

So even pro-trade members of Congress are wary of trade votes. No politician wants to hear the wrath of out-of-work constituents on local TV news or splashed across negative campaign advertising come election time. Obama and his team have plenty of hard work ahead to convince even Republicans that a vote in favor of his trade deals won’t be Exhibit Number 1 when a political opponent want to suggest that he or she has lost touch with voters. One otherwise pro-trade GOP lawmaker privately said, “Give us an excuse not to vote on trade.” Steamrolling Democrats into a pro-trade vote may prove even harder.

The common wisdom is that Republicans need a sizable corpus of Democrats to fall on their swords and vote yes on trade deals. That number could be as few as 20 in the House, but the smaller the number, the greater the chance recalcitrant Republicans who feel electorally vulnerable will refuse to go along.

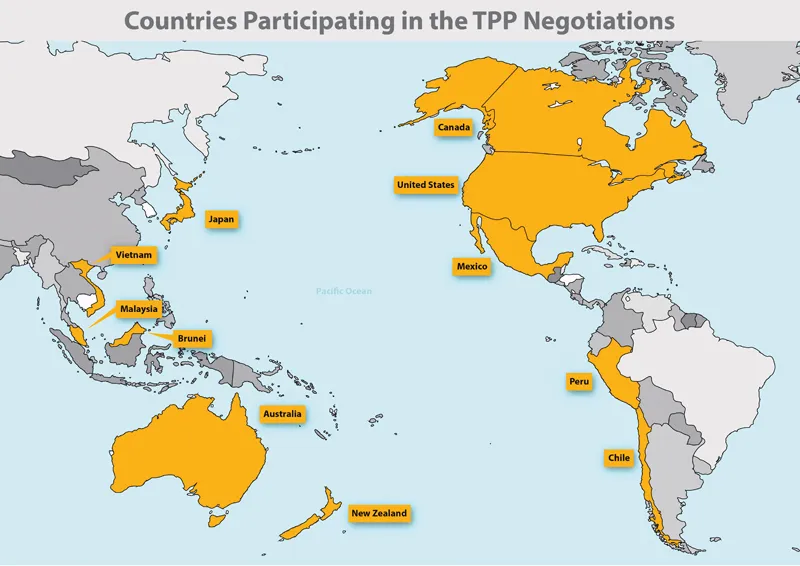

At primary issue is the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a free trade agreement being negotiated with 11 other countries in the Asia-Pacific region. The economic rationale for the TPP is significant. Trade within Asia has been booming, largely in component parts that have been assembled into finished products in China and exported primarily to the United States and Europe. The TPP would draw the United States closer to the boom.

But the economics are changing because Asians are getting richer. This is having two effects. First, Asians are increasingly able to buy more things from abroad. Second, the United States as a manufacturing center is becoming more viable as production in Asia is becoming more expensive, although don’t expect many new jobs on the assembly line here, unless you are a robot or a semiconductor chip. So putting the TPP in place is a way to set the table for American competitiveness in the broader regional economy as it develops.

Whatever its economic merits, it is the strategic imperative of TPP that may be driving the White House to demand its passage. Getting an agreement in place would be the signature piece in the president’s platform to “rebalance” or “pivot” to the world’s fastest growing region. The trade deal would cement the role of the United States as the prime mover on regional economic and strategic architecture. If TPP fails, the international power, prestige and economic clout of the United States will suffer a grave setback. The stakes are large.

The president’s trade team, led by U.S. Trade Representative Mike Froman, is composed of the most canny and skilled negotiators on the planet. Negotiations are largely closed to public scrutiny. A more public process would gum up the works, although there is genuine and reasonable concern about the lack of transparency among lawmakers, who view the regulation of commerce as a congressional power. But those who have had access to the current text of the agreement are encouraged by what they’ve seen. But even Froman’s team cannot overcome what the 11 other countries in the negotiations know, which is that Congress has final constitutional authority to establish the terms on which the United States trades. Without some method of preventing Congress from amending TPP, the final deal will look almost nothing like what Asian nations agree with Obama’s negotiators.

This is why other all America’s trade partners are waiting anxiously for Obama to be granted trade promotion authority (TPA). Until he gets it, they will not give their final, best offers to the his negotiators. TPA would force an up-or-down vote on the deal the president sends to Congress. But who in Congress, Republican or Democrat, is eager to give the president a blank legislative check on any issue these days? Republicans, particularly those on the Right, are loath to provide him with powers the the Constitution otherwise reserves to Congress. Democrats, smarting from their election losses of 2014, which many ascribe to Obama’s unpopularity, aren’t keen on helping him burnish his legacy, particularly with an issue that splits his base. Talk of “steamrolling” probably doesn’t do much to advance the cause.

Supporters of trade and the TPP are hoping that the president’s alternatively vaunted and lampooned skills as a community organizer will be brought to bear and knit together this fractious community. Similar efforts by the Clinton and Bush administrations involved all hands on deck and late-night phone calls by the president to individual lawmakers.

The pro-trade community is cheered by recent talk that Obama will create a whip group of cabinet officers chaired in the White House to rally support for first TPA and then TPP (and then, possibly, for a trans-Atlantic trade and investment partnership with Europe). But if the President is truly going to launch a campaign with the kind of retail politicking necessary to drive “yes” votes on trade, it would be a solitary outlier in the otherwise-aloof legislative strategy practiced by this White House. After all, the president’s signature piece of legislation, the Affordable Care Act, was notoriously passed with a White House legislative strategy that consisted primarily of cheering from the sidelines.

If the legislative activity on trade is as buzzing as some in the administration suggest, it’s a little alarming that few if any of the key members and staffers on the Hill seem to have heard from anyone at 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. purporting to be whipping their votes. Froman has thus far been the frontman selling the trade agenda, but despite his strengths, he can’t deliver the votes to pass the agreements he is negotiating with other countries.

What’s in the TPP will affect the politics involved in passing it. There is a delicate balance in the construction of trade agreements. The administration almost certainly will attempt to inject new provisions into it that will reduce the ability of other countries to use lax labor and environmental regulations as a competitive trade advantage. These provisions aim to respond to demands from the Democratic base that, to paraphrase opponents of the deal, “trade agreements shouldn’t only be about trade.” However, strong labor and environmental provisions are far from likely to win votes from lawmakers who fundamentally dislike trade.

The primary beneficiaries of trade liberalization are, after all, private sector companies whose agenda is held in deep suspicion by the Left. Despite the fact that only around 15 percent of the private sector workforce is organized, the labor movement is deeply antagonistic to market-opening trade agreements that are perceived to place U.S. workers under new pressures. The environmental movement views trade agreements as race-to-the-bottom exercises, and will lobby bitterly against a TPP regardless of new provisions to raise environmental standards.

If the president wants progress on other parts of his policy agenda — the trade agenda only took up 15 sentences of an hour-long State of the Union address — he will need the support of his base. And traditional progressive constituencies have warned that spending too much political capital on trade will imperil their support on other issues.

If the Obama administration will find it difficult to appease the Left, a TPP that seems focused more on left-of-center concerns than on opening markets will undermine the interest of the business community in rallying support for passage. As a trade association executive lamented recently, “There’s a big difference between business saying its for trade legislation — and it will be almost as a knee-jerk reaction — and actually committing resources and CEO time to lobby on behalf of that legislation.” Thus far, not much time or money have been committed by the business community to get out the vote on either TPA or TPP. Business leaders, and not just Washington representatives of American businesses, will need to make the trek to Capitol Hill personally for members to be comfortable voting for trade.

Appeasing all these constituencies is complicated. Further complicating the task is the fact that the political process in Washington has a global audience, and the messaging behind a pro-TPP narrative is read far beyond the Beltway. Other TPP members will attempt to read the process with a view to finalizing their offers, which in some cases will be complicated by domestic political events back home. Some will rush to complete TPP even before TPA is granted to avoid the appearance of being captive to U.S. politics. Although some analysts believe that TPP could be passed through Congress even absent TPA, it would make an already fraught process that much riskier. “I hope,” said one Republican trade staffer, “they’re smarter than that.”

Even beyond the TPP countries, other eyes are watching goings-on in Washington carefully. During the State of the Union speech, the president raised the specter of competition with China as a reason to pass trade legislation. “China wants to write the rules for the world’s fastest-growing region,” he said. It may have been a message intended only for the Hill — fodder for the China paranoia that sometimes drives legislation. But the administration has for years been trying to convince China that the TPP and the “pivot to Asia” were not about containing China’s rise. The State of the Union speech complicated that message, and official and unofficial Chinese reactions were blistering. The White House will have to smooth over those ruffled feathers to manage that most important strategic relationship, even if it is very likely that anti-China rhetoric will be an important part of the overall narrative behind the whip votes on Capitol Hill.

Momentum behind a TPA bill could pick up quickly. Rumors that the Senate Finance and House Ways & Means Committees are moving to mark up bills in February and March could begin to crank up the political machinery. And that will start to test the ability of the White House to cajole individual members into supporting the bill. That will take a willingness to respond to district-by-district requests for favors in areas other than trade. It will require the administrative to help develop narratives that provide members with answers to the question: “Why did you vote for this bill.” Figuring out what members want for their votes and delivering on those asks is new territory for this White House, and will take an awful lot of support from pro-business lobbyists with which this White House has sought to avoid contact since the start of the Obama presidency.

Finally, the reality of the political calendar is lost on no one. With the President’s term now ticking down to 23 months left, and with little love lost between Republican leaders and the White House, it’s possible that the GOP might pass trade promotion authority in hope of handing it off to the next president, whom they hope will be a member of their party. Trade promotion authority with a the TPP deal is not a legacy either the president or his fellow Democrats would be proud of.

It would also be playing poker with American power and prestige abroad. The stakes are high. But the politics of trade are low indeed.

Charles W. Freeman III is the International Principal at Forbes-Tate, LLC. A former USTR official, he advises companies in support of TPA and TPP. Forbes-Tate represents a variety of interests in the trade debate.