At the Pentagon’s Lab Day, Naval Research Laboratory scientist Raymond Gamache found himself face-to-face with the reason he’s had to keep making body armor better.

Inside his booth at the Pentagon’s first-ever science fair, a soldier checked out the new body armor plates Gamache has developed — flexible, interlocking mesh that floats in water.

“I’ve got a piece of ceramic on a necklace from one of my [old] sapi plates,” the soldier told him, referring to a sliver from the life-saving armor plating that saved his life. “It almost looks like obsidian when it breaks.”

Gamache’s booth was one of dozens that lined the outside courtyard of the Pentagon Thursday to showcase what the Defense Department’s internal researchers and inventors are fielding to make combat safer, to make weapons more precise, and in a few cases, add a bit more variety to the meals ready to eat (MREs) that soldiers in remote posts rely on for food.

In Gamache’s case, he was tackling the problem that soldiers often ditch their armored vests, because they’re heavy and difficult to quickly react in. So Gamache started to think of ways to make the plating “flex” and make it lighter.

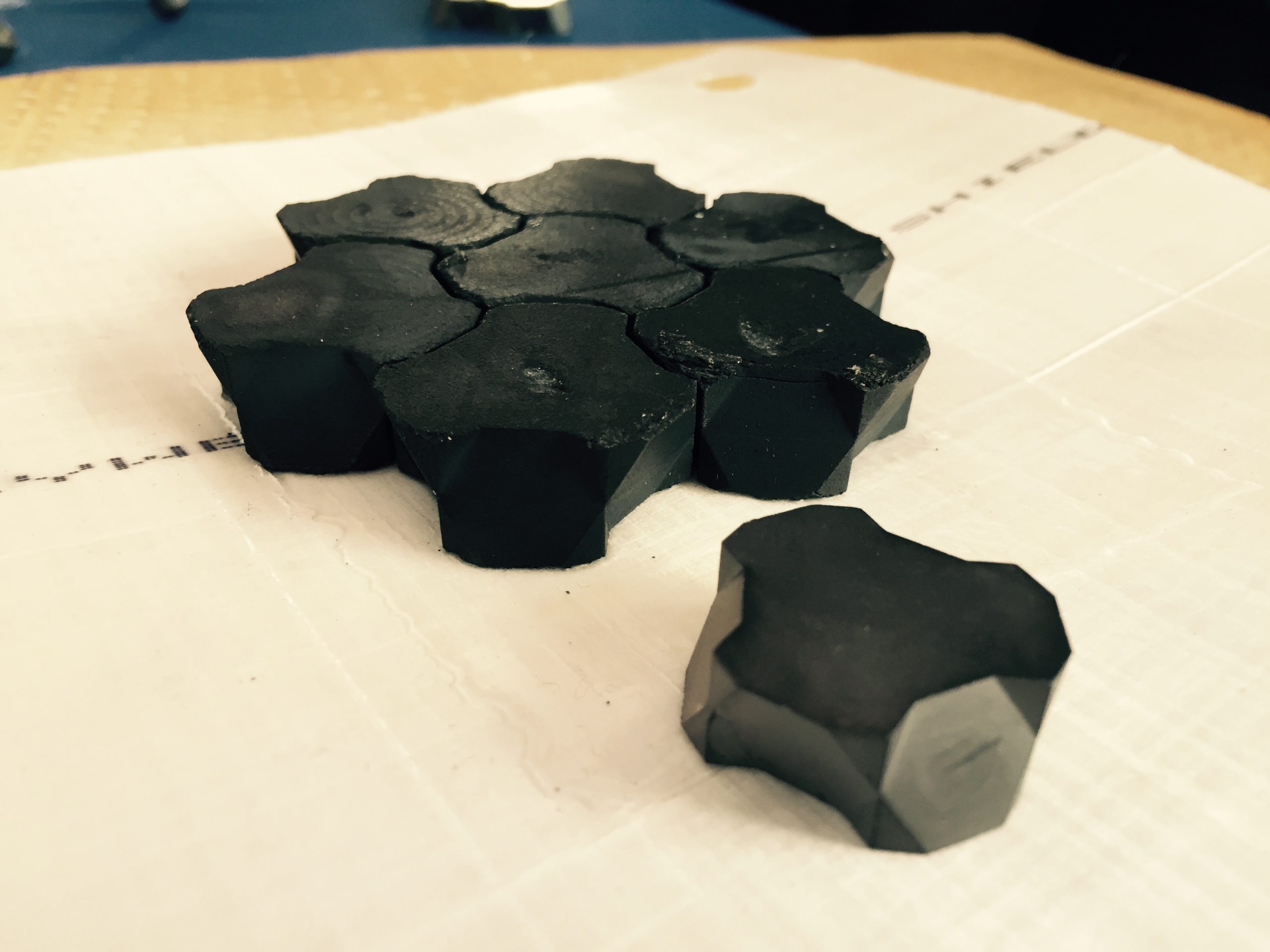

The result: a hexagonal, interlocking system of angled puzzle pieces made super-light by boron carbide and titanium carbide.

Using a hexagon with interlocking angles allows the new armor to be flexible as a soldier moves, and then snap into place when hit by a projectile. (Tara Copp)

A typical sapi plate is about seven pounds, the interlocking system is about five pounds.

“Very common structure used in armor is a hexagonal, a six-sided piece, because its has essentially three-fold symmetry,” Gamache said. “Because I knew it had three-fold symmetry, I said, ‘I want to start making it interlocking.’ So I started machining down the edges.”

What the design accomplished was a puzzle of hexagons that link at the angles. They flex with soldiers’ movements, but will lock up upon impact.

“The whole idea here is the geometry — in armor one of the issues you have to deal with is that if a bullet goes into one of the seams, it’ll go right through. When a bullet hits here, it’s not like it has a straight shot through — it will actually be bent off to one side.”

Gamache said the armor could be fielded in about six months if the Pentagon moves forward with it.

Also exhibited at the fair: food.

Stephen Moody is the director of combat feeding for the Army’s research, development and engineering command. A few years ago, the Army came to him with a request: Find a way too add calcium and vitamin D to the military’s MREs. Commanders were seeing too many stress fractures among their newest soldiers, Moody said, and they suspected that the amount of time their newest recruits had spent in front of a computer or TV screen rather than outside had affected bone strength. They lost a lot of training time to medical issues.

So Moody’s team developed the “First Strike Bar,” a rich chocolate dessert bar that tastes a lot like the Little Debbie Snacks brownies sold in vending machines and convenience stores.

The Army’s combat feeding directorate was asked to develop a food rich in calcium and vitamin D, when the Army began to notice that its latest recruits, possibly from years in front of a TV or computer screen, did not have adequate bone strength and were getting stress fractures. (Tara Copp)

From the Army’s point of view, “it is lightweight and calorically dense, making it a critical component in the combat ratio,” weighing in with 1,000 milligrams of calcium and 50 micrograms of vitamin D.

Then there’s the pizza, which has been the holy grail of MREs for years.

“That’s the most requested item we’ve had for decades,” Moody said. But pizza eluded them, because the storage requirements for MREs — foods that can last on the shelf in their brown plastic MRE bags for three years at 80 degrees, or six months at 100 degrees without starting to deteriorate, had been been impossible with pizza. Either the crust got soggy or the sauce dried out.

But pizza is to be added to MREs by 2017. The pepperoni-flavored pizza tasted a bit like the Totino’s pizzas found in most college dorm fridges, and just as salty.

It took the Army years to develop its most-requested menu item – pizza – because it was difficult to meet the standards of creating a food that could remain on the shelf for three years at 80 degrees without either the crust getting soggy, or the sauce drying out. The new pizza will be in the 2017 meals ready-to-eat (MRE) menu for troops. (Tara Copp)