The lead investigator who accused top officials at the Department of Homeland Security of playing politics with his investigation into the Secret Service prostitution scandal retired in August under a cloud.

David Nieland, the head of the DHS inspector general’s Miami office, left the job in mid-August.

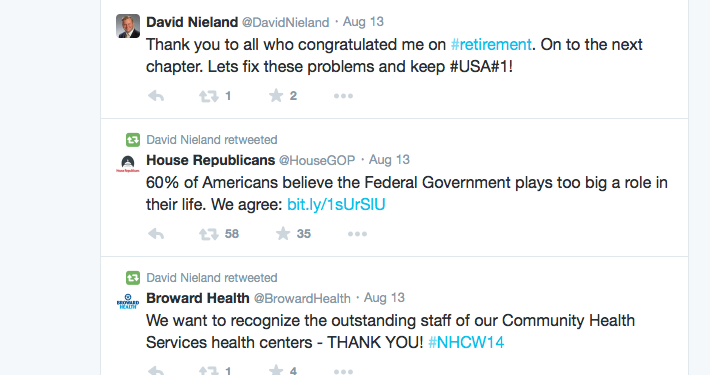

“Thank you to all who congratulated me on #retirement,” he tweeted on Aug. 13. “On to the next chapter. Lets (sic) fix these problems and keep #USA#1!”

Nieland didn’t return several phone calls from the Washington Examiner over the course of a week inquiring about the circumstances surrounding his departure from the inspector general’s office.

A spokesman for the DHS inspector general told the Examiner Wednesday that “Mr. Nieland separated from federal service on Aug. 9.”

“As a matter of policy, the OIG does not comment on investigative or personnel maters,” the spokesman, William Hillburg, said.

Hillburg did not respond to a question about whether Nieland received retirement benefits when he left the inspector general’s office.

The New York Times Tuesday night reported that Nieland resigned in August after an incident involving a prostitute in early May in Broward County, Fla.

In the Times story, Hillburg is quoted as saying that Nieland left because DHS officials had uncovered evidence of misconduct.

“While the law prohibits us from commenting on specific cases, we do not tolerate misconduct on the part of our employees and take such allegations very seriously,” Hillburg, a spokesman for the inspector general’s office, told the Times.

“When we receive information of such misconduct, we will investigate thoroughly, and, during the course of or at the conclusion of such an investigation, we have a range of options available to us, including administrative suspension and termination,” Hillburg continued.

The Times also cites an email from Nieland denying the misconduct.

The allegations against Nieland and his departure from the DHS inspector general’s office add a new twist to the ongoing scandal involving Secret Service agents hiring prostitutes in Colombia in 2012.

They do not, however, change many troubling facts uncovered in recent weeks about the way then-acting DHS Inspector General Charles Edwards mishandled the Secret Service prostitution investigation or the White House’s lack of candor with the public on the matter.

The Washington Post ran a story Oct. 8 with the headline “Aides knew of possible White House link to Cartagena, Colombia, prostitution scandal.”

The story accuses the White House of failing to fully investigate or publicly acknowledge circumstances in Colombia implicating the volunteer aide’s alleged involvement in the prostitution scandal.

Unlike many of the Secret Service agents who lost their jobs over the scandal, the aide was never polygraphed and went on to a position at the State Department.

The aide, the son of a well-connected lobbyist and Democratic donor who now works for the Obama administration, through an attorney has vehemently denied the allegations that he hired a prostitute.

In that story, the Post quotes Nieland’s testimony to Senate staffers.

“We were directed at the time … to delay the report of the [Secret Service prostitute] investigation until after the 2012 election,” the Post quotes Nieland.

The Post also said Nieland said his superiors told him “to withhold and alter certain information in the report of investigation because it was potentially embarrassing to the administration.”

The story also says after the prostitution scandal first broke in April 2012 then-Secret Service Director Mark Sullivan gave the White House hotel logs from the Colombia trip showing that a woman had logged into the White House aide’s room on one of the nights during his stay.

GOP ties

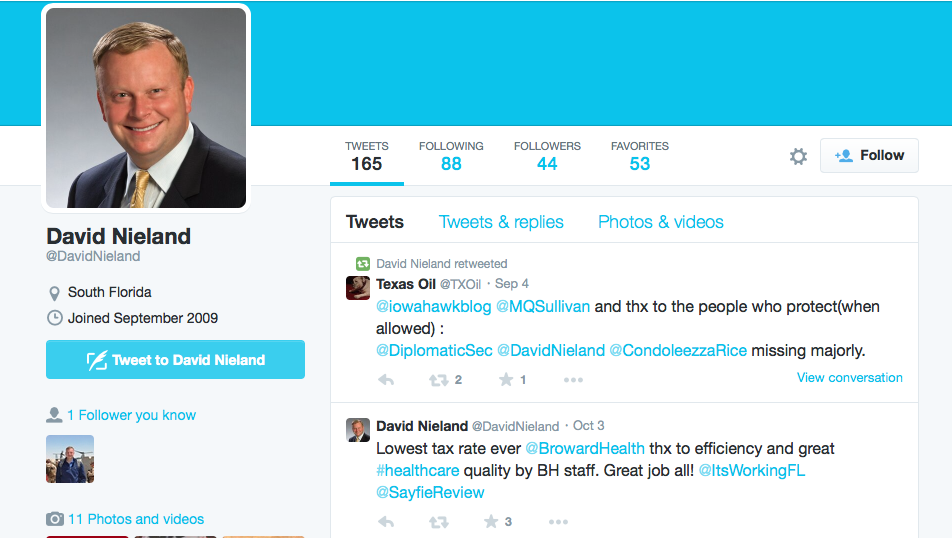

Meanwhile, public statements by Nieland on social media, and his appointment to a Florida state government board, may raise questions about his objectivity in conducting the prostitution investigation.

Florida Gov. Rick Scott, a Republican, appointed Nieland last year to the North Broward Hospital District Board of Commissioners, according to a hospital press release.

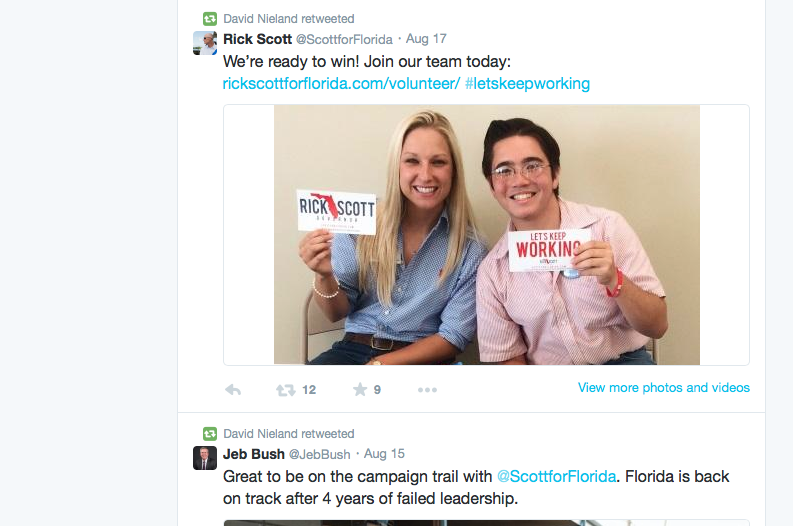

Nieland often tweets about tax cuts, as well as Republican politicians and lawmakers. In August, he retweeted Scott’s campaign recruiting message, as well as former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush’s support for Scott.

“We’re ready to win! Join our team today: rickscottforflorida.com/volunteer/ #letskeepworking,” he retweeted on Aug. 17.

“Great to be on the campaign trail with @ScottforFlorida. Florida is back on track after 4 years of failed leadership,” Jeb Bush tweeted Aug. 15, which Nieland retweeted.

The hospital, in its release, touted Nieland’s work for the State Department’s Diplomatic Security Service and his multiple awards, including being named federal agent of the year by the Law Enforcement Officers’ Charitable Foundation.

Nieland is a former North Carolina police officer and ambulance medic. He also co-founded iMarshals, a nonprofit organization that uses social media to locate missing persons and fugitives, as well as to identify threats to schools. He was a finalist for South Florida U.S. Marshal in 2009.

Building the case

While Nieland’s political leanings and departure from DHS may hurt his credibility, there are layers of claims by multiple whistleblowers, as well as documents, that corroborate many of the allegations he and many others made in the Secret Service prostitution case.

The existence of the hotel logs alone in the Post story — and the White House’s failure to acknowledge them in 2012 — raise additional questions about the administration’s handling of the Secret Service prostitution scandal.

Specifically, the hotel log and many elements of a Senate investigation raise questions about whether Edwards worked with senior Obama administration officials to sanitize his final report on the matter and delay it until after the president’s re-election to avoid more embarrassment to both the Secret Service and the White House.

Jay Carney, the then-White House press secretary, shortly after the Secret Service prostitution scandal story broke said “there have been no specific, credible allegations of misconduct by anyone on the White House advance team or the White House staff.”

More recently, White House spokesman Eric Schultz has argued that similar hotel logs mistakenly implicated a Secret Service agent who was polygraphed and later absolved of any wrongdoing in the prostitution scandal.

Schultz also has pointed to a reference to the potential involvement of a White House staffer in an initial and preliminary DHS inspector general’s report, known as a Report on Investigation, on the matter in September 2012 as proof that there wasn’t a cover-up.

In that report, Edwards acknowledged “one reported member of the White House staff and/or advance team who had personal encounters with female Colombia nationals consistent with the misconduct reported” based on interviews and a review of the records.

That initial report was never publicly released, is not posted on the DHS inspector general’s website, and there is no mention of a White House aide’s involvement in Edwards’ final report, titled “Adequacy of USSS’ Internal Investigation of Alleged Misconduct in Cartagena, Colombia.”

In a cover letter to the ROI sent to DHS Secretary Janet Napolitano, Edwards tells her to “please destroy the ROI upon disposition of this matter.”

That final formal report, which Edwards released more than three months later, made no recommendations to the Secret Service on the way it handled its internal investigation into the matter.

Nieland was one of many employees in the office who accused Edwards of inappropriate behavior while Edwards was serving as acting inspector general, and more specifically, during the office’s investigation into the Secret Service prostitution scandal.

The Senate subcommittee on financial and contracting oversight, which investigated the allegations of Edwards’ misconduct and issued a report in April, conducted voluntary interviews with 35 current and former OIG officials, according to its final report.

That Senate investigation never looked into allegations of a White House cover-up of one of its aides’ potential involvement in the prostitution scandal. Instead, it focused on broader allegations against Edwards and ultimately found that he inappropriately altered and deleted his investigative reports and failed to uphold the independence of his watchdog office by informing and working with top DHS officials.

‘The importance of independence’

By law, inspectors general are required to be independent and objective units within their respective federal agencies.

The Secret Service probe was bipartisan, but ultimately controlled by the Democratic majority. Sen. Claire McCaskill, D-Mo., heads the subcommittee and Sen. Ron Johnson, R-Wis., is its ranking member.

“Mr. Edwards did not understand the importance of independence,” the subcommittee concluded in its final report. “Mr. Edwards communicated frequently with DHS senior officials and considered them personal friends.”

The report clearly states that Edwards “did not obtain independent legal advice,” directed reports to be “altered or delayed to accommodate senior DHS officials” and “did not recuse himself from some audits and inspections that had a conflict of interest related to his wife’s employment, resulting in those reports being tainted.”

The committee found that certain information in a draft report on the Secret Service’s Colombia prostitution issue, which was circulated within the inspector general’s office, was altered or removed from the body of the final report.

The deleted information included damaging information about the Secret Service, such as inaccurate testimony by a Secret Service official to Congress, a “good old boys” management network that condones and engages in similar behavior, and prior compromises that placed the president and national security information at risk.

The DHS inspector general’s final report also did not include any mention that the Secret Service obstructed the inspector general’s office in its investigation of the Colombia prostitution scandal and did not cease its investigation upon the inspector general’s request, jeopardizing the independence of the probe.

Nieland was among a group of whistleblowers who leveled some of the most serious charges against Edwards, including accusing him of playing politics with the Secret Service prostitution investigation in order to lessen the public scandal before President Obama’s re-election.

But the 25,000 pages of documents the Senate subcommittee reviewed throughout its investigation provided plenty of other evidence of Edwards’ misconduct. Edwards also refused to turn over his emails to the panel.

Other whistleblowers provided numerous examples of Edwards’ conflicts of interests and inappropriate behavior and argued that he was trying to ingratiate himself with the right people to win a promotion to the full inspector general role.

The Senate subcommittee also looked into whether Edwards retaliated against Nieland, as well as the associate counsel and the counsel to the DHS inspector general’s office, by placing them on administrative leave.

“Each of these individuals believed they were placed on administrative leave as a form of retaliation,” the panel concluded.

The Office of Special Counsel conducted an independent review into the matter and determined that there was a “prima facie case” for Edwards’ retaliatory actions against one of the staffers, according to the Senate report. That staffer was the only one to file an OSC complaint.

Edwards also frequently emailed both the DHS chief of staff and its acting counsel and socialized with top agency officials outside of work over drinks and dinner. The chief of staff at the time was Noah Kroloff, who later founded a private security firm with Sullivan, the former director of the Secret Service.

In one email, Edwards told Kroloff that he truly valued his friendship and that his “support, guidance and friendship has helped me be successful this year.”

After the Senate issued its report on Edwards in late April, DHS Secretary Jeh Johnson placed Edwards on paid administrative leave, on which he remains, collecting his full six-figure salary.