For 30 years, the Goldwater-Nichols law has served as the bedrock of the modern military command structure. It governs everything from how the Defense Department’s top leaders are organized, to how it buys weapons, to who actually advises the president on military matters.

Its inception traces back to the “blatantly obvious” need for the services to do a better job talking to each other after battlefield errors and failures in Vietnam, Grenada and the Iran hostage crisis. The law completely changed the command structure at the highest levels of the Pentagon, and effectively turned the leaders in charge of the services into trainers and equippers, not commanders of troops. In their place, regional leaders, such as the head of U.S. Central Command, were given a direct line of communication with the secretary of defense, sidestepping the service chiefs. And it made the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff the primary military adviser to the president.

And this year, it could all start to change.

Top lawmakers on Capitol Hill now say the pendulum has swung too far, giving service chiefs too little say over their respective services. Making training and equipping the No. 1 job of service chiefs has led to a lack of accountability on weapons programs, they say. On Capitol Hill in 2013, for example, the chief of naval operations couldn’t answer who was responsible for a $2 billion cost overrun in procurement of the aircraft carrier Gerald R. Ford.

In the push to get away from service parochialism, “jointness,” the pursuit of understanding how all the departments work together, has become paramount. Officers are required to serve a certain amount of time in a joint billet even if it’s not related to their future career plans. Too much of this has hurt career progression for the military’s top officers.

On Capitol Hill in 2013, the chief of naval operations couldn’t answer who was responsible for a $2 billion cost overrun in procurement of the aircraft carrier Gerald R. Ford. (AP)

The process also means too many employees are involved in decision-making, which slows acquisition to a crawl. That’s an even more significant problem as the pace of technology advancements explodes. By the time the service is able to field technology, it’s already out of date.

To fix this, lawmakers on the armed services committees launched a comprehensive review of the entire law as threats shift and technology advances.

“Our nation is at a key inflection point,” Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, told The Arizona Republic. “The military’s technological advantage is eroding and eroding fast precisely at the time that the world is on fire. Our failing defense acquisition system is no longer just a budgetary scandal, it is a national security crisis.”

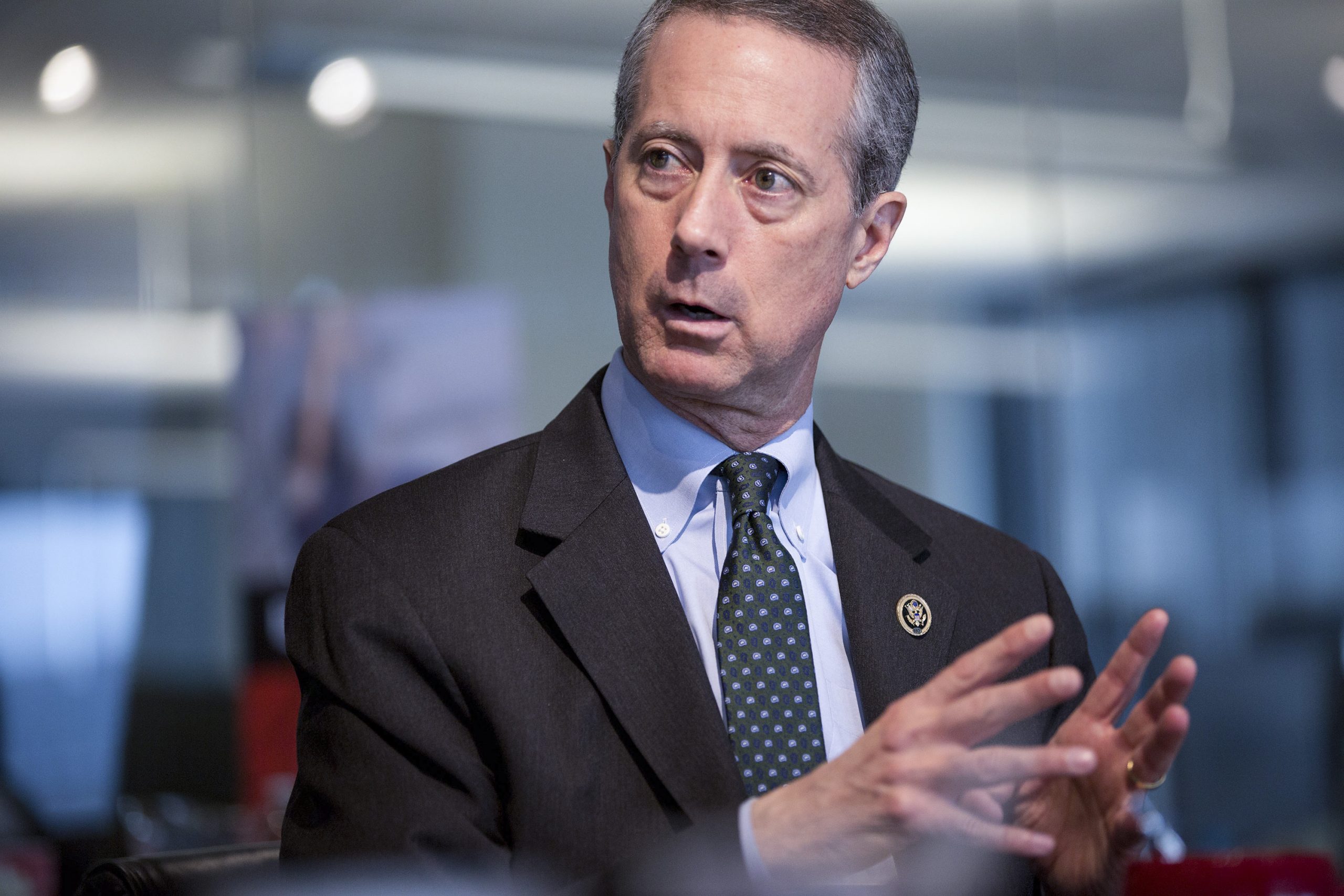

McCain and his counterpart in the House, Rep. Mac Thornberry, are two of the most qualified men to tackle these changes that could upend the way the military operates as its core, analysts say. And the pair has already proven it can get things done. Last year’s defense policy act including first steps toward acquisition reforms.

“McCain and Thornberry both really are as knowledgeable and committed to these things as anybody I’ve seen,” said David Johnson, an analyst with RAND Corp. “These two folks have spent their careers learning about this and figuring out how to improve it. The question is how much can they get done in the present circumstances.”

The Pentagon also seems eager to change the way the top ranks are organized. In remarks previewing his budget for fiscal 2017, Defense Secretary Ash Carter said he will receive recommendations soon on which Goldwater-Nichols Act reforms the department should make.

“The military’s technological advantage is eroding and eroding fast precisely at the time that the world is on fire.” (AP)

“We’ve been doing a thorough review for the last several months, and I expect to begin receiving recommendations on that in coming weeks and making decisions,” Carter said during a speech at the Economic Club in Washington.

But analysts cautioned not to expect seismic changes, such as reorganizing regional combatant commands, all this year. And members of Congress themselves have acknowledged that the entire structure of the military can’t be flipped on its head in one year.

“We can’t fix DoD personnel, acquisition, organizations in a single bill or even in a single Congress, and I don’t think we should try,” Thornberry said at the National Press Club. “We should take measured steps, listening carefully to everybody involved in the system, especially to the end user, who are the war fighters, and then take further steps.”

What went wrong

The organizational structure proposed by Sen. Barry Goldwater, R-Ariz., and Rep. William Flynt Nichols, D-Ala., sought to address problems the military faced in the 1980s by improving how the services worked together. The act made the chairman of the Joint Chiefs, not the service chiefs, the top military adviser to the president and stripped service chiefs of their control over troops. That power moved out of Washington and toward leaders of regional combatant commands.

Johnson said dysfunction among the branches was so bad back then that services were acquiring incompatible gear so they couldn’t even talk to each other. As one story goes, a general literally had to put the antenna of an Army radio out of a Navy ship’s porthole because nothing on the ship could talk to communications devices on shore.

“Whether that’s true or not, that story came to symbolize how the services were developing capabilities that weren’t compatible,” he said.

The reorganization sought to eliminate competition between the services and required high-ranking officers to serve at least some time in a joint job to encourage cooperation.

The need for the services to do a better job working together was most deeply illustrated in the failed “Desert One” rescue attempt of the Iranian hostages in 1980. During preparations, a helicopter crashed into a transport plane, killing eight troops. The debacle, involving all four services and a series of errors, served as a catalyst for Goldwater-Nichols.

Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama both expanded their national security councils, leading to what some see as micromanaging of the issue by the White House. (AP)

Now, analysts agree that the 30-year-old law needs revisiting, but said the lack of such a black-and-white disaster at war could make it difficult for lawmakers to pull the trigger on reforms.

“Whether something comes out in four years or five years is not going to be of the same urgency as … having to scrub a mission to save a bunch of hostages,” Johnson said.

In the fiscal 2016 National Defense Authorization Act, Congress made some changes to this organizational structure by beginning to streamline the acquisition process. One of the biggest changes gave the services more power in the acquisition of new technology to increase accountability.

Under that law, service chiefs and secretaries are to be more involved in the early design process for new acquisitions and must sign off on projects in an effort to keep them more on-time and on-budget.

Marc Numedahl, vice president of Capitol Strategies Partners LLC, said the changes in last year’s bill eliminated many institutional barriers within the Pentagon that made it easier for the military to buy commercial goods, especially as most innovation happens in the private sector.

“It opens up a lot of new areas so a lot of non-traditional suppliers, those who don’t traditionally do business with DoD, now have more avenues to get their goods in the department,” said Numedahl, who previously served in the Pentagon’s office of acquisition, technology and logistics. “It will provide more competition in industry, add more ideas and push industry to continue to evolve, which is a good thing for the warfighter and taxpayer.”

That should make it easier for the military to buy equipment from the private sector, where much of the cutting edge innovation is happening. In turn, this allows troops to get the best and most up-to-date gear.

Navy Secretary Ray Mabus also said at a Brookings Institution event that those changes fixed problems that took the “customer” out of the acquisition process by taking too much responsibility away from the service chiefs.

Navy Secretary Ray Mabus (AP)

Yet there’s a downside to giving the services too much control over their acquisition, Numedahl said. Services tend to rush through the early work for programs to get to “milestone B,” often considered the official beginning of a program. In it, a branch uses previous research to decide whether to begin manufacturing and development.

Once that occurs, you pass a point after which “they have a program that’s really hard to kill,” he said. The NDAA put in place some safeguards to encourage services to slow down and conduct due diligence in the early parts of the acquisition process.

But, beyond the fiscal 2016 bill, Thornberry said there’s still more to be done to speed up the bureaucracy.

“The Defense Business Board says about half of all uniformed personnel serve on staffs that spend most of their time going to meetings and responding to tasks from the hundreds of offices throughout DOD, including 17 independent agencies, nine combatant commands and 250 joint task forces. Needless to say, we’ve got a lot of simplifying to do,” Thornberry said.

Leaders in industry said they welcomed the proposed changes and that involving the service chiefs’ more in acquisition will increase leadership and accountability.

“Currently, the requirements, budget and acquisition processes are not linked, and are too complex and costly,” James Thomas, director of legislative policy at the National Defense Industrial Association, told the Washington Examiner in a statement. “They are uncoordinated both at inception and during execution. The service chiefs should serve as a link for these major processes.”

Goldwater-Nichols also shapes who in the Pentagon talks to the president. While the law made the Joint Chiefs chairman the primary military adviser to the Oval Office, his isn’t the only voice that influences the commander in chief. Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama both expanded their national security councils, leading to what some see as micromanaging of the issue by the White House. Dakota Wood, an analyst with the Heritage Foundation, said it’s important to remember that, while Goldwater-Nichols is important as it dictates some of who advises the president, a lot is also up to the discretion of the president. And that could change under the next administration.

“If one is suggesting changes need to be made, but those thoughts are informed by how things worked over the last seven or eight years, you have to take into account the environment within which those things were occurring,” he said. “The next president could have a dramatically different way of working: maybe less insular, maybe a smaller NSC, maybe a different secretary of defense, or presidential relationship where the secretary of defense is really is in the inner circle of the commander in chief.”

First steps

“We can’t fix DoD personnel, acquisition, organizations in a single bill or even in a single Congress, and I don’t think we should try.” (AP)

Both leaders of the armed services committees began holding a series of hearings on the issue last year, which will continue into 2016. McCain stressed in November that lawmakers will focus their time and effort first on defining the problem, then on finding a solution, which he said must be as bipartisan as Goldwater-Nichols was.

McCain told the Washington Examiner that his first steps this year will include “examination of the commands and the [combatant commanders] and also a lot of the personnel policies.”

McCain expanded on his priorities, saying that he would look at things like why U.S. Africa Command is based in Germany and whether the military needed a U.S. Northern Command and a U.S. Southern Command.

“Why should there be an arbitrary line at the Mexico/Guatemala border?” McCain said at a Defense Writers Group breakfast last month.

In addition to a push to get something done on Capitol Hill, Carter’s remarks signal that the Pentagon is onboard, too.

Analysts say a rethinking of the military’s command structure is needed now, both because the threats the country faces can’t be confined to a single geographical command and because a creeping acquisition process is not compatible with today’s rapid technological advancements, especially as the U.S. tries to close a technology gap with competitors China and Russia.

Johnson said he expects to see lawmakers tackle larger reforms of the acquisition system to speed it up, make it more agile to changing requirements and give uniformed personnel more of a voice in what the product looks like. Making changes to the acquisition process also would not be politically difficult, he said, though it may be a heavy lift to cut through layers of bureaucracy.

“Acquisition reform doesn’t bump into meddling in someone’s headquarters while they’re fighting a war,” Johnson said. “If you can make it better, it’s a clear win, you save money, field things faster and are more agile.”

Wood said Congress’ best bet could be to commission a major study and give investigators sufficient time to sort through issues and possible solutions.

“Sometimes those can be used to avoid making decisions, but sometimes, it’s time and effort well spent,” Wood said.

He pointed to the Military Compensation and Retirement Modernization Commission as a good example, where officials took a significant amount of time to look at an issue and make recommendations that ended up succeeding in Congress.

Johnson said to look for some “quick wins” since all players involved could be facing the end of their tenure at the end of 2016. A new administration will almost definitely mean a new defense secretary, and McCain could lose the chairman’s gavel if Democrats regain control of the Senate.

“McCain wants to get something done while he’s there. He’s been involved in this forever,” Johnson said. “The question is what do they think is feasible to do in an election year with a couple wars going on.”

Some weren’t so convinced that a thorough study of the military’s organization would lead to major changes. Michael O’Hanlon, an analyst with the Brookings Institution, said he expects lawmakers to discover that modest changes, rather than a major overhaul, are a better route to improve efficiency within the Pentagon.

“It’s not obvious to me what problem we are trying to solve, apart from the possibility of very modest savings through efficiencies, and we could definitely make things worse if we aren’t careful,” he said. “We shouldn’t change for change’s sake.”

“You’ve got al Qaeda, ISIS and others whose operations and presence spans geographic boundaries, so it’s not just a CENTCOM fight, it also has manifestations in Asia and Africa.” (AP)

Future years

Despite McCain’s statement that he plans to shake up the structure this year, analysts speculate that a reorganization of the regional combatant commands that plan military strategy and provide advice and intelligence to the president may be too lofty a goal for just 12 months.

The military is split today into nine combatant commands, but the threats America faces no longer fit neatly within those lines drawn on a map.

“You’ve got al Qaeda, ISIS and others whose operations and presence spans geographic boundaries, so it’s not just a CENTCOM fight, it also has manifestations in Asia and Africa,” said Wood, referring to Central Command, which oversees operations in the Middle East. Other examples are Pacific Command and Northern Command, which is based in Colorado and oversees homeland defense. “How does the U.S. deal with a transregional threat? Nobody thinks that’s going away any time soon.”

This may be especially true when looking at the cyberbattlefield. If U.S. Cyber Command is trying to attack an enemy online who is physically located in Europe, do cyberwarriors need to coordinate with European Command? Under today’s force structure, there are no clear answers to things like this that’ll likely only become more prevalent.

In December, Joint Chiefs Chairman Gen. Joe Dunford said the Pentagon’s combatant command structure needs a reorganization to address and make recommendations on threats that span more than one region.

But Johnson said he didn’t expect lawmakers to tackle a reorganization of combatant command structure now, since U.S. Central Command is in the middle of a war.

“That’s a pretty significant change,” Johnson said. “The reluctance to do that will be you don’t want to change what’s on the field while there’s a war going on. You don’t want to do major muscle movements with CENTCOM when they’re engaged against ISIS and the Taliban.”

An election year will also limit the amount of time lawmakers can spend in Washington attending hearings and writing legislation, since they will need to split their time campaigning in their home districts in the latter part of the year.

Still, Thornberry said he and McCain will not be discouraged by those who point to the hurdles they face in passing major reform through a Congress often plagued by gridlock in a shortened election year.

“We’re not going to be sidetracked by all the voices who say, ‘Oh, there’s no use trying, it’s just too hard, it’s just too complicated, too big a mess, don’t worry about it.’ We are going to fulfill our responsibilities under the Constitution,” he said.