They have little money in savings, half are young, and a third are racial minorities.

They are the 10.5 million people eligible for Obamacare coverage who, two years since enrollment began, still haven’t signed up through the insurance marketplaces created for Obamacare.

Experts agree that these will be the hardest people to convince to buy healthcare coverage. They’ve remained uninsured through two signup seasons, because they don’t believe they can afford it, don’t think they need it, or haven’t heard about it.

But what surprised many this month is that the Obama administration not only agrees that reaching the uninsured is a big challenge, but that it expects to enroll barely more this year than it did last year. This would leave the number of marketplace enrollees at fewer than half those originally expected by the end of 2016.

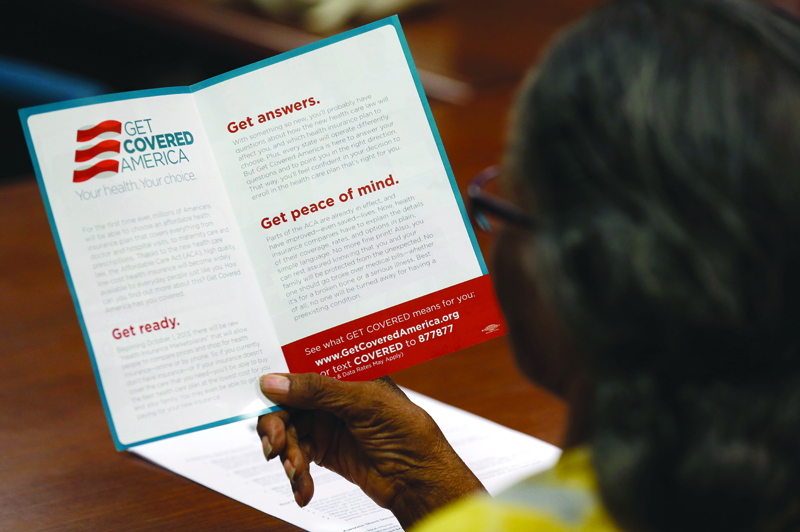

There are 10.5 million Americans eligible for Obamacare coverage who still haven’t signed up. (AP file)

Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia Mathews Burwell announced in mid-October that her goal is only 100,000 more paid enrollees than the agency achieved last year. In June, 9.9 million people had paid for Obamacare coverage; during this enrollment season, Burwell hopes for 10 million people to pick a plan and pay the premiums.

“We believe 10 million is a strong and realistic goal,” Burwell said. “We’ve seen high levels of satisfaction with the marketplace and expect the vast majority of our current customers will re-enroll. And our target assumes that more than one out of every four of the eligible uninsured will select plans.”

But that will still leave a significant number of people, at least 7 to 8 million, lacking insurance through their employer, qualifying for the Obamacare exchanges, and yet still uninsured when enrollment closes at the end of January.

Add to that the people who are eligible for Medicaid but haven’t enrolled and those who would have been eligible for Medicaid had their states expanded the program, and there’s unlikely to be a big reduction in the approximately 32 million people who still don’t have coverage six years after Obama signed the reform bill into law.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that the uninsured rate is below 10 percent for the first time in American history. (AP file)

The uninsured rate dropped from 16.2 percent to 12.1 percent from 2013 to 2014, and in August, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that it’s below 10 percent for the first time in American history.

But the administration’s modest enrollment projections underscore future challenges, and make it vulnerable to criticism from Republicans keen to point to shortcomings in law they’ve repeatedly tried to repeal.

“They got the low-hanging fruit already,” said Tim Jost, health law professor at Washington and Lee University and a leading proponent of the law. “If you don’t have universal coverage, how do you reach people, many of whom have very little money, very frantic lives, very little education? They’re not people out there shopping the Internet for anything, much less insurance coverage.”

Advocates of the law face the simple fact that for people on low incomes, health insurance is dauntingly expensive. The administration estimates that half of the uninsured have less than $100 in savings, and nearly eight in 10 have less than $1,000.

While the tax penalty for remaining uninsured increases for the 2015 tax year to $325 or 2 percent of adjusted income, it’s doubtful that this will prove a big incentive to low-income people. Most will qualify for a hardship exemption; in fact, the Congressional Budget Office has estimated that all but 7 million of the remaining uninsured will be exempt from the fine.

The administration’s modest enrollment projections underscore future challenges, and make it vulnerable to criticism. (AP file)

“It’s not clear how much the penalty motivates a lot of people whose very low incomes make them exempt,” said Judy Solomon, vice president for health policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

These Americans’ meager savings makes them extra vulnerable should unexpected healthcare costs arise. But it also makes it hard to convince them to take on an extra monthly payment for insurance that they may not need in the immediate future.

“They really struggle with this choice,” said Anne Filipic, president of Enroll America, a group formed explicitly to enroll people under the new law.

Filipic, whose group has offices in about a dozen states and has employed around 230 people during past enrollment seasons, said she’s learned about good and not-so-good ways to convince low-income people to buy coverage.

During the first year of enrollment, Enroll America put a lot of effort into telling stories of individuals who obtained health coverage for the first time and how it changed their lives. They ran these one-minute ads in targeted markets when signups started. But they’re not doing that anymore, Filipic says, because it’s just not an effective tool for persuading the uninsured.

“It might be nice to see a nice story about someone else who has benefitted, but really what they need to know is what does this mean for me,” Filipic said.

Enroll America has offices in about a dozen states and has employed around 230 people during past enrollment seasons. (AP file)

Instead, Enroll America is launching an online tool that helps shoppers compare plans side-by-side and gives them an estimate of their costs based on answers to personal health questions. A big complaint about signing up for insurance has long been that it’s difficult to comparison shop when the plans are so complex, with so many different elements such as premiums, deductibles and co-payments.

Many consumers are intimidated by the whole process and don’t even begin — even if they might qualify for federal subsidies to help afford the coverage. About eight in 10 of those eligible for marketplace plans also qualify for subsidies. And that’s also a major barrier to helping those with low incomes enroll, Filipic says.

“They can be the top audience because they really have limited expendable income,” she said. “At the same time, that’s the same audience that can see the most amount of financial assistance.”

Of the adults who have visited the Obamacare marketplaces but didn’t buy a plan, 57 percent said it’s because they couldn’t find an affordable option, according to a September survey by the Commonwealth Fund. And because many with low income are exempt from the individual mandate to buy coverage, that’s not a motivator for them.

“Affordability is going to be challenge, there’s no doubt,” Solomon said. “I think that report Secretary Burwell cited makes very clear at low incomes you have multiple demands on your resources and what’s going to be paid is going to be a hierarchy that’s personal to you.”

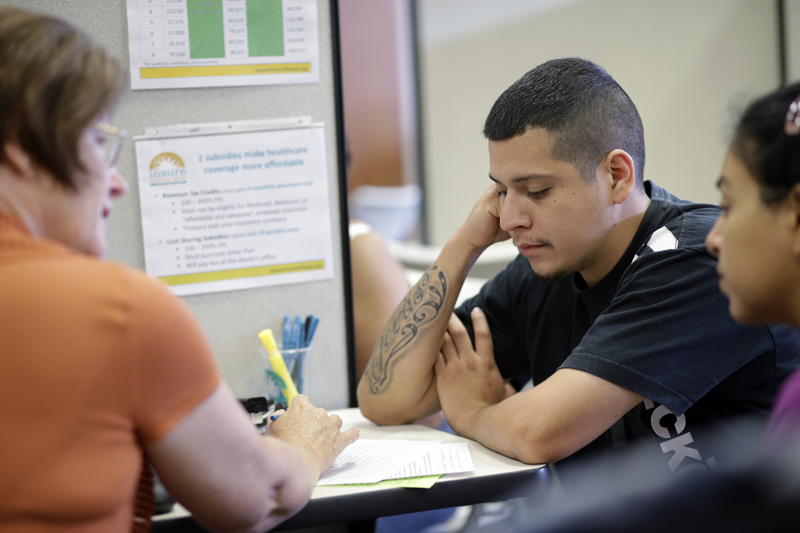

Many consumers are intimidated by the whole healthcare sign-up process and don’t even begin. (AP file)

The Commonwealth survey found that just 11 percent of those who shopped but didn’t choose plans earned too much to qualify for the assistance. The rest either qualified for subsidies or Medicaid or lived in the 19 states that haven’t expanded Medicaid and thus fall into a “coverage gap” where they can’t get any financial help.

Advocates for the healthcare law largely blame the uptake problems on people just not understanding they qualify for help. But opponents are blaming the plans themselves and the law’s failure so far in actually lowering healthcare costs.

Yuval Levin, a conservative healthcare policy analyst at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, said the administration’s relatively low enrollment projections grow out of a “recognition that the exchange system is failing to attract consumers.”

“It doesn’t allow insurers to offer attractive and economically sensible products,” Levin said.

And on the cusp of the enrollment season, Republicans are still doing their best to ditch the law. The House has passed a measure repealing many of its major parts through a process known as budget reconciliation, which requires just 51 votes in the Senate to pass. President Obama is certain to veto the legislation should it land on his desk, but the GOP wants to force him into it as the 2016 presidential election ramps up.

The administration has said it’s focusing on key areas around the country where uninsured rates remain especially high. (AP file)

Setting the bar at an assuredly attainable height is a smart political move for Burwell and her agency, most agree, as it saves them from having to explain next year if enrollments came in below target. That’s the strategy the administration employed last year, estimating that just 9.1 million Americans would sign up and pay for coverage.

But it has also reignited some criticisms that the Affordable Care Act isn’t changing the country’s insurance landscape as originally envisioned. In June, the Congressional Budget Office said the law would result in 20 million Americans having marketplace coverage in 2016.

The agency had downgraded that number from its original August 2010 estimate of 21.6 million Americans on the exchanges by 2016. And in April that year, the actuary for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services pegged the number at 24.8 million people.

The enrollment projections also come at a time when insurers are unhappy they’re not getting all the paybacks they had hoped for to cushion the risk of taking on sicker customers. They had requested $2.87 billion in so-called “risk corridor” payments, which were supposed to compensate insurers with higher than expected medical losses from a pool of money collected from insurers who had lower than expected medical claims. But only 12.6 percent of that amount is available, CMS announced recently.

“The insurance companies are losing money on Obamacare and they’re losing money because we don’t have enough people enrolled,” said Bob Laszewski, a consultant at Health Policy and Strategy Associates. “And the administration just said we’re not going to enroll any more people.”

In June, the Congressional Budget Office said the law would result in 20 million Americans having marketplace coverage in 2016. (AP file)

Modest enrollment projections notwithstanding, advocates for the law say they’re focusing resources where they’re needed the most. The administration has said it’s focusing on five key areas around the country where uninsured rates remain especially high: Dallas, Houston, northern New Jersey, Chicago and Miami. Enroll America is adding staff on the ground in Alabama, Illinois and South Carolina.

One area in the country that could serve as a model for outreach is Massachusetts, which has achieved the lowest uninsured rate in the country a decade into its own health reform law.

The uninsured rate there now stands around 4 percent, but the Boston-based nonprofit Health Care For All is trying to get that down to zero, in part using a first-time Affordable Care Act “navigator” grant from the Department of Health and Human Services. The group’s executive director, Amy Whitcomb Slemmer, says it has learned two key things about reaching the low-income uninsured: Reach people in their primary language and ensure they have in-person assisters.

Like Enroll America, HCFA has learned that simply running ads narrating personal experiences with health insurance isn’t convincing enough. You have to sit down with someone and help them through the process, Slemmer said.

“The personal stories may get people’s attention, but it doesn’t necessarily mean they’re going to pick up the phone and spend what can be an hour-long process to fill out an insurance application,” she said.

A big component, nearly everyone says, is making sure non-English speakers can present questions to a helper in the language they’re most comfortable using. Hispanics are the largest minority group among the uninsured, comprising about 19 percent according to HHS.

Enrollment advocates have made strides among Hispanics and blacks — whose uninsured rates dropped faster over the last two years than among whites — but they lacked insurance at such high numbers to begin with that there’s still a lot of ground left to cover.

A big component, nearly everyone says, is making sure non-English speakers can present questions to a helper in the language they’re most comfortable using. (AP file)

“Those most likely to remain uninsured are also demographic groups and communities where we’ve made some of the greatest progress,” Filipic said. “But the reality was the disparity was so significant there are still a disproportionate amount of folks who are uninsured.”

Slemmer admits that sometimes, it’s still hard to convince people they can afford a monthly premium despite the federal subsidies. A family of four earning $40,000, for example, would have to pay around $278 per month for a mid-level silver plan, after subsidies. An individual earning $25,000 would have a monthly cost of $143 when subsidies are factored in.

And insurance is generally out of reach for those living near the federal poverty level in the states, generally Republican-led, that haven’t expanded Medicaid under the healthcare law. To qualify for subsidies on the exchanges, they must be at 133 percent of federal poverty.

“For some folks, health insurance is still going to be unaffordable,” Slemmer said. “For us, that is a fail because we want everyone to be covered and have access to healthcare.”