In the past week, Judge Amy Barrett has taken fire from multiple organizations due to her placement on the “shortlist” as a potential Supreme Court nominee.

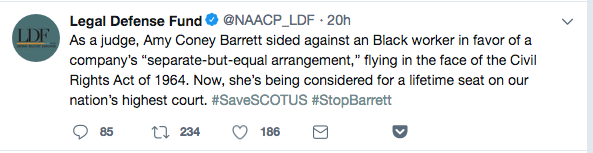

The NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund (LDF) took to Twitter, accusing Barrett of siding “against an [sic] Black worker in favor of a company’s ‘separate-but-equal arrangement.’” (The Center for American Progress tweeted out the same accusation through a secondary account.) [Update, 4:10 p.m., July 3. The LDF has deleted its tweet but CAP’s tweet remains.]

The Alliance For Justice also claimed that Barrett “sided against an African American worker who had been transferred to another store because of a company’s policy of segregating their employees by race and ethnicity, finding that the company’s ‘separate-but-equal arrangement is permissible.’”

While the LDF does not clarify which case it is referring to—and did not respond to TWS Fact Check’s request for clarification—Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. AutoZone, Inc. is the only case remotely close to Barrett that fits LDF’s description, as it was considered by the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals.

However, the case was decided by a three-judge panel in June 2017, almost four months before Barrett was appointed. Weeks after Barrett took her place on the 7th Circuit in November, the full panel decided to refuse the EEOC’s appeal.

“On Nov. 21, the full panel of judges at the U.S. Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals in Chicago announced its refusal to reconsider a three-judge panel’s decision earlier this summer to reject the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s case against auto parts seller Autozone,” the Cook County Record reported at the time. According to the decision, when “a judge in active service called for a vote on the request for rehearing en banc” a 5-3 “majority of judges in active service voted to deny rehearing en banc.” Barrett voted to deny the rehearing.

The claim that Barrett “sided against an African American worker” is incorrect because she was not on the three-judge panel in EEOC v. AutoZone.

Other claims surrounding the case are also misleading.

Kevin Stuckey worked in the sales department for AutoZone from 2008 to 2012. Stuckey was transferred between stores in the Chicago area multiple times without “any loss in pay, benefits, or job responsibilities,” according to the panel’s opinion.

The district manager, Robert Harris, who decided upon and oversaw Stuckey’s transfers, including the one in July 2012, is also black. The store manager of the Kedzie location Vernon Harrington, who Stuckey did not get along with, claimed that Stuckey requested to be transferred from the store, something that Stuckey “did not recall.”

Stuckey testified that Harris was trying to “keep the store hispanic,” and claimed this was the primary reason for his transfer.

Stuckey admitted that he “‘didn’t mind’ being transferred from the Kedzie store” and “also acknowledged that Harris never made any comments about his race or the race of any other Auto-Zone employee.” The store he was transferred to was closer to his listed address as well. In all of this, Stuckey’s pay, benefits, and responsibilities were not reduced in any way. According to the opinion, “Rather than accept the transfer, Stuckey chose to abandon his job; he did not report for work at his new assignment.” He then “filed a charge with the EEOC claiming that AutoZone discriminated against him because of his race in violation of Title VII.”

The panel argued that “it’s well established that a purely lateral job transfer does not normally give rise to Title VII liability under subsection (a)(1) because it does not constitute a materially adverse employment action” and decided “the district judge properly entered summary judgment for AutoZone.”

In Chief Judge Diane Wood’s dissent on the majority decision to deny the rehearing en banc (before the bench), she argued that “the panel’s opinion, as [she] read it, endorses the erroneous view that ‘separate-but-equal’ are consistent with Title VII.” Wood wrote that “the statute’s broad language—which extends to actions that ‘tend to deprive any individual’—does not require a factual showing any more extensive than the one that the Commission already has provided.”

The panel’s opinion addresses this interpretation of Title VII (one that the EEOC also argued) that evidence beyond what the EEOC provided is not required to demonstrate that “which would deprive or tend to deprive any individual of employment opportunities or otherwise adversely affect his status as an employee, because of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.”

“That reading cannot be squared with the plain statutory text,” the panel’s opinion stated, determining that the EEOC must “prove that the challenged action adversely affected his employment opportunities or status” under Title VII.

Regardless, claiming that Barrett was a part of this three-judge panel is, and forever will be, incorrect.

If you have questions about this fact check, or would like to submit a request for another fact check, email Holmes Lybrand at [email protected] or the Weekly Standard at [email protected]. For details on TWS Fact Check, see our explainer here.