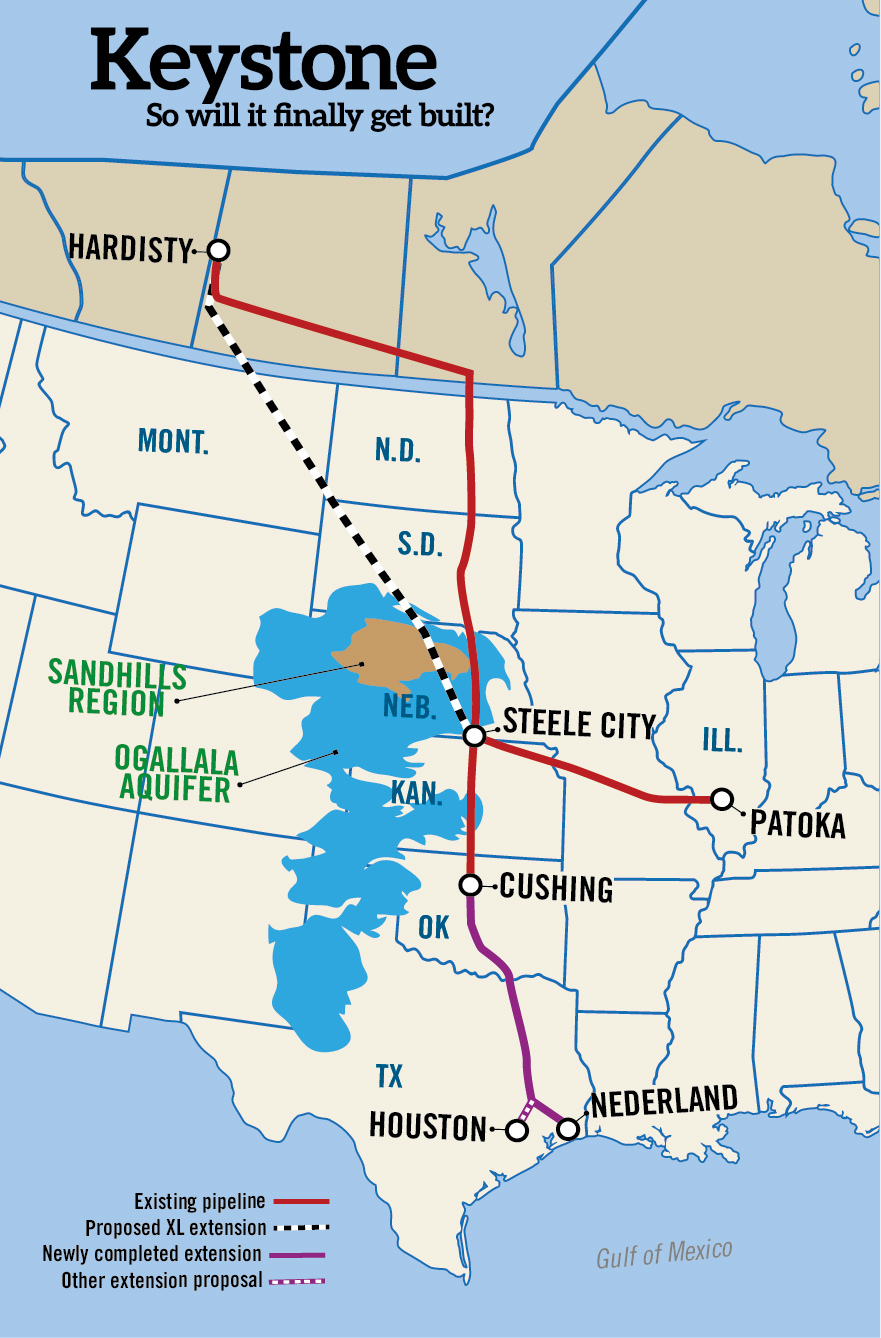

National opposition to the Keystone XL pipeline has centered around climate change, but it first drew fire over a route that would have taken the Canada-to-Texas project through environmentally sensitive regions in Nebraska.

Ranchers, farmers and other landowners along the planned route voiced concerns that TransCanada Corp.’s oil sands pipeline would disrupt Nebraska’s Sandhills region. Worries mounted that a spill into the Ogallala Aquifer, a massive source of drinking water, would be expensive if not impossible to clean up after a 2010 oil sands pipeline spill in western Michigan’s Kalamazoo River that still hasn’t been remediated.

To appease local protests, TransCanada offered another path that it said avoided the Sandhills. Environmentalists said it did no such thing.

The State Department said in November 2011 that it needed to analyze the new plan; President Obama agreed, and Foggy Bottom began another environmental review that didn’t wrap up until January. The pipeline has been under federal review for more than six years, as TransCanada needs a cross-border permit to complete the northern leg.

Separate from the federal review, the Nebraska state legislature hoped to speed the process when it passed a law that Republican Gov. Dave Heineman signed in 2012 that fast-tracked approval of the new route.

That move has now come under scrutiny.

The Nebraska Supreme Court is weighing whether the law is constitutional, as the state’s utility regulator is usually charged with making infrastructure decisions. A ruling is expected any day.

The Obama administration’s inter agency review of the State Department’s environmental report, the last step before the agency determines whether Keystone XL is in the national interest, is on hold until that case is resolved.