Medical research in the U.S. is getting the biggest infusion of taxpayer funding in more than a decade, now that Congress has designated $2 billion extra for the National Institutes of Health this year.

The move received lots of acclaim over the holidays by the medical research community, which for years has bemoaned the NIH’s declining purchasing power and the increased difficulty for medical researchers to win grants funding their work.

One of those groups is Research!America, a nonprofit committed to making medical and health research a larger priority in the country. The Washington Examiner recently spoke with the group’s President Mary Woolley about the stroke of good news for her cause and challenges ahead.

Washington Examiner: As you know, NIH is getting $2 billion more this year under Congress’ year-end spending agreement. Are you happy with the new funding level?

Woolley: It doesn’t make up for a lot of lost ground in terms of resources that then translate to research that didn’t happen over the past decade-plus. But it does mark a breakthrough and turnaround. For the first time in many years, so many members of Congress are not only talking about their commitment to research, but also delivering on that commitment.

But this is not what we really need to ensure medical progress in a way that really does find solutions to what ails us as individuals, as families and as a nation. A lot more needs to happen. To use a sports metaphor, we can think of this as our champions have brought us to the kickoff point, but we are not by any means in the end zone.

But we who are committed to advancing medical research are in the game now, and our goal is to really stay there to make research for public health a top priority in this nation. We want to have a long list of candidates for president and the Senate and the House who will be talking about this issue.

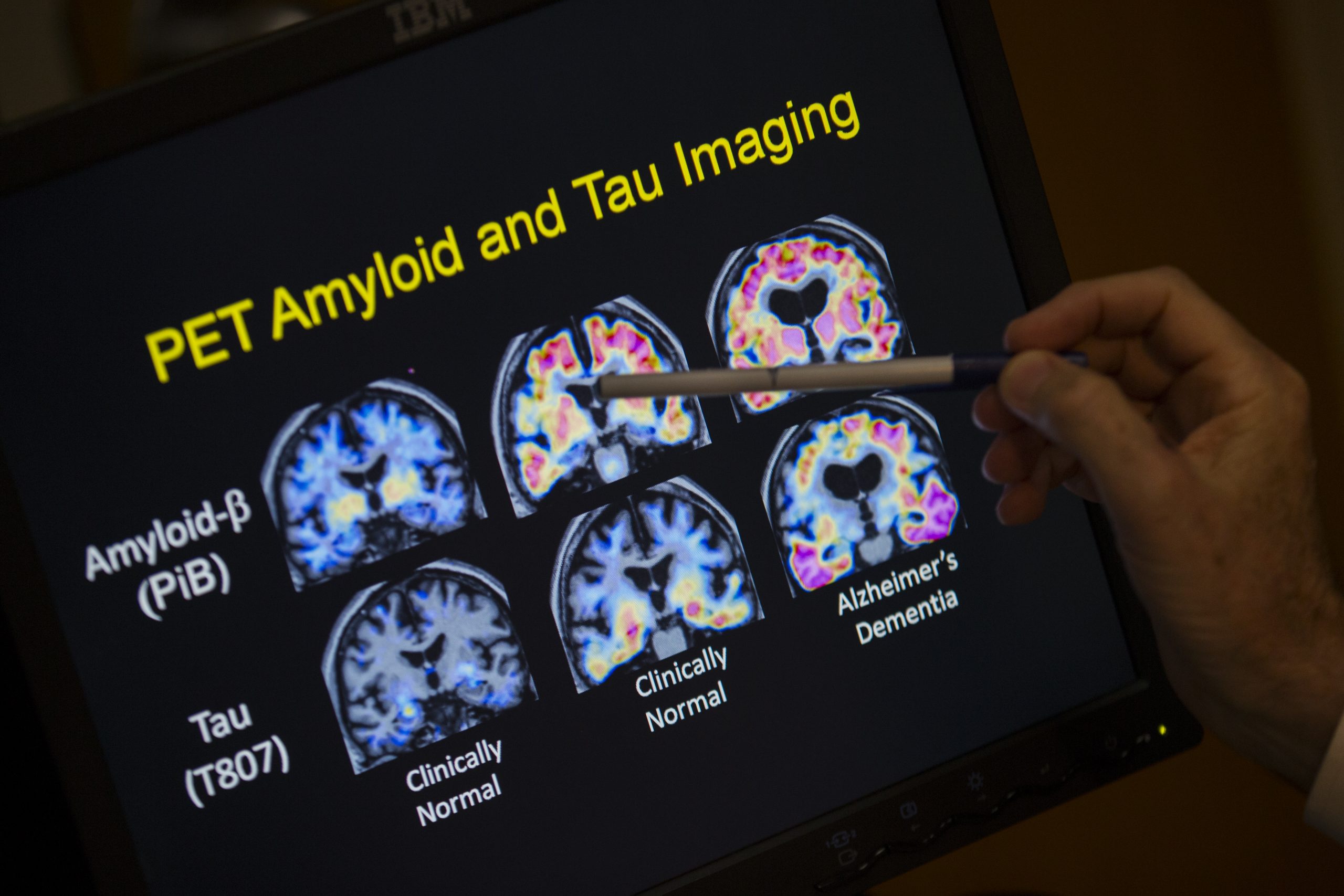

“Much of the new money has been allocated for research on the brain, Alzheimer’s disease, precision medicine and efforts to fight antibiotic-resistant bacteria and opioid abuse.” (AP)

Examiner: Much of the new money has been allocated for research on the brain, Alzheimer’s disease, precision medicine and efforts to fight antibiotic-resistant bacteria and opioid abuse. Are you happy with where it’s going?

Woolley: Yes is the short answer to that. There was a lot of science input by the NIH into the Congress’ decision-making. But I want to emphasize that it’s not adequate for accomplishing perfectly reasonable expectations of the American public that their tax dollars will be used to do everything within the power of research to find the answers. That is simply not happening right now. It’s a real breakthrough moment that Congress is stepping up as it had done in the previous decades, but now we’ve got to drive it intensively forward.

Examiner: NIH Director Francis Collins has been begging Congress for extra funding for years. Why do you think it took lawmakers so long to respond?

Woolley: Sometimes people in the advocacy community think medical research is championed by one party and not the other. As an interesting rough marker, out there on the NIH campus there are quite a number of buildings named for former members of Congress, five are Republicans and seven are Democrats. My point is that it is a bipartisan issue, biomedical research, but it often takes the alignment of champions from the same party.

We have had that this past year, especially with [Rep. Tom Cole] as the chairman of the House Appropriations Labor/HHS subcommittee and Sen. Roy Blunt as his counterpart on the Senate side. They have for a long time been outspoken supporters of NIH and medical research. Now they’re champions. That has been a key ingredient, as has the bipartisan backing of their ranking members and leadership in the Congress.

Examiner: Do you fear Congress won’t continue the funding bump beyond this year?

“[We’re] getting to the point once again where research for health and science generally is a top priority along with defending our nation, education, transportation — things people live with day in and day out.” (AP)

Woolley: No. I think fearful is the wrong characterization here. We have every reason for optimism. There’s no pushback on people running for office when they fund medical research and this is an election year. The opposite is the case, so in my mind I’m not fearful at all.

We really are committed to turning this moment into a movement and getting to the point once again where research for health and science generally is a top priority along with defending our nation, education, transportation — things people live with day in and day out. When we talk about defending the country, we need to defend it from disease and disability as much as we do from terrorism.

Examiner: How do you determine how much medical research funding is enough?

Woolley: We’re a long way from pushing the limits of what’s possible in translating the ideas of scientists into discovery and then into cures. So when you ask about how much is enough, you’re also begging the question of how much cure is enough, what will we be satisfied with? We know from public opinion surveys that people want research to move faster and they want more support behind it. So it isn’t a problem with public sentiment.

The marker often used at the NIH to indicate how much science is being conducted is the [funding] success rate for proposals and it is now — depending on the institute and the area of the research — more or less around 15 percent, in terms of success rate of qualified proposals. In previous years it was more than double that success rate. So you can loosely say we’re at a point again that it would not be a waste of taxpayer dollars to double the NIH budget again.

Examiner: What do you see as the most promising areas of medical research at the moment?

“We’re moving from a one-size-fits-all kind of approach to a one-size-fits-one.” (iStock)

Woolley: I would certainly say precision medicine is one of these. It’s rightly gotten a lot of attention. We’re moving from a one-size-fits-all kind of approach to a one-size-fits-one. That’s where we want to be, that’s where the power is. There’s also lots of promise right now in really defeating diabetes with a variety of new technologies. There’s just so much, there’s the new microbiome work that’s very exciting.

Examiner: Which countries are investing the most in medical research right now? Do you see them as a model for the U.S. to follow?

Woolley: Other countries actually have consciously adopted what used to be the day-in-day-out U.S. model of supporting science. Those include China, Korea, Germany reinventing itself very successfully as a science powerhouse, the U.K., Europe generally. We are different in the U.S., having invented the playbook for modern times, but we’ve put it aside and that is not lost on our competitors, China in particular.

Examiner: What about the Food and Drug Administration’s role? What reforms would you like to see there?

Woolley: The 21st Century Cures bill that passed overwhelmingly in the House in July was something we are really in support of. We believe … it will be conferenced and signed into law in the first six months of this year.

One of the things it will do is to give the FDA more flexibility to use regulatory science to apply that in a 21st century way, rather than being burdened by constraints created in the last century. It’s also going to include ways to incorporate much more patient voices, patient wisdom in defining what’s acceptable and what isn’t to patients in situations that involve compassionate use of medications or other real world, life experiences that are very far from one size fits all.

Examiner: I’ve heard concerns about an imbalance of funding toward diseases that have effective public awareness campaigns, like breast cancer or HIV/AIDS, versus other serious diseases that don’t have the same kind of PR push. Do you share those concerns?

Woolley: I look at it with a longer view. I remember very well when it wasn’t even possible to talk about things like breast cancer publicly. It was a hush-hush conversation. The breast cancer advocacy changed that in a dramatic and welcome way, thank goodness.

Other groups have learned a lot from that experience. If you think of the gold standard in terms of what HIV/AIDS activist accomplished, what happened as advocates were driving it, that’s the kind of advice and observation I offer to others who are worried the disease or condition they’re worried about is not getting enough attention.

It’s not robbing Peter to pay Paul; it’s about doing more for everybody. But we can’t blame groups that really did the breakthrough work of really raising public consciousness and public attention to killer diseases.