It’s not enough to be the biggest business lobby anymore.

To wield the influence required to push business interests successfully, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce has evolved into a major political force — developing candidates, picking sides in primaries, buying ads and getting out the vote.

The 102-year-old organization, which historically has spent more time in the halls of Congress than on the campaign trail, in 2014 took on the Tea Party in the GOP primaries and liberals in the general election. It is preparing for even more in 2016.

“We did it, and we’re going to do it again,” says Chamber President Tom Donohue.

In an interview ranging over a variety of topics, Donohue lays out the priorities of the business lobby and how he plans to achieve them. As President Obama nears the end of his tenure and the 2016 elections draw close, the Chamber is devising a strategy to install the kind of Congress it wants to see.

The Chamber represents business and it’s officially nonpartisan, but it rarely helps Democrats. It’s looking for candidates who can “govern.”

PART 1: Fiscal train wreck

What that means is that it supports Republicans who are not too ideological and who aren’t going to embarrass other GOP candidates or threaten business priorities once they win office.

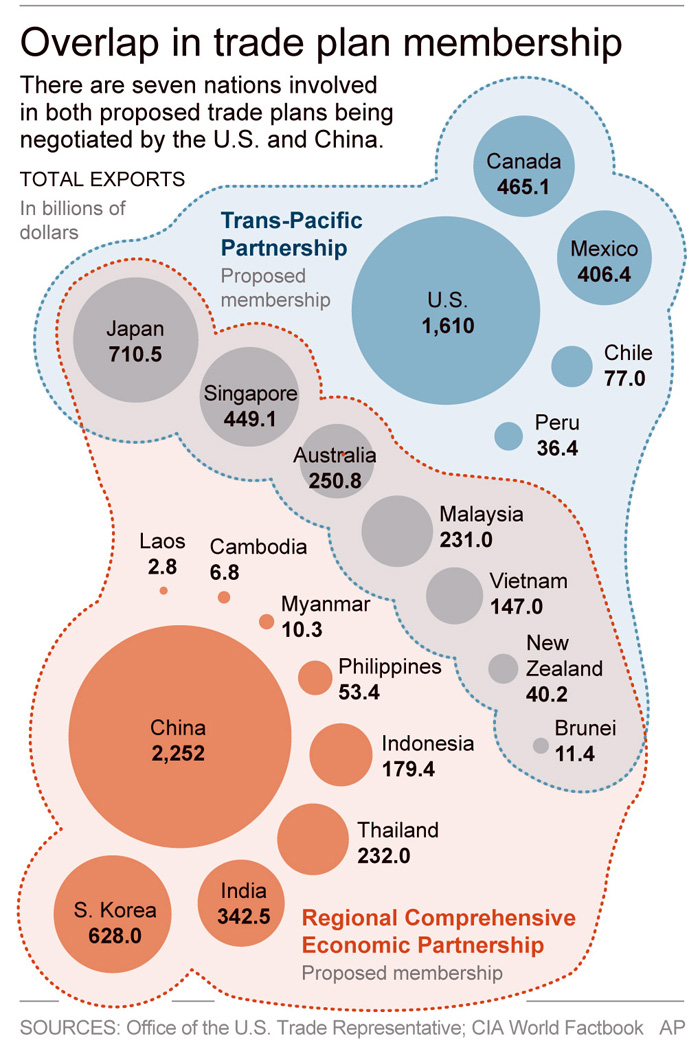

The test of a candidate’s readiness to govern is whether he aligns with the Chamber on several key issues: Trade, immigration, oil exports and infrastructure spending. Those are the “pointy spear” issues, Donohue says, that weigh more heavily in judging aspirant pols than do hundreds of other policies the Chamber advocates. They are the litmus tests.

Despite its growing influence, which helped tip the Senate to Republicans and install the biggest GOP majority in the House since Herbert Hoover was president, the Chamber wants more.

It has been frustrated in achieving some of its biggest goals: The immigration system is broken and reform legislation is dead. The country’s broken roads, creaking bridges and sclerotic ports need updating and maintenance. But infrastructure spending is getting squeezed.

“We want to get better on closing the deal,” Donohue says, setting his expectations for 2016.

PART 2: Comrades in arms

Closing the deal may be getting harder. Not only does Obama, a frequent opponent, still occupy the White House, but many Republicans are moving toward a populist, anti-big-business conservatism.

This is clear on several pressing agenda items: Reauthorization of the Export-Import Bank, immigration reform, and government spending.

Those are all areas in which conservatives are likely to pick a fight with business, which can’t look for help from a Democratic Party that has moved further left in recent years.

But Donohue and the Chamber are willing to bet that their influence can keep the Republicans on the side of business and in the majority.

‘We’re just getting started’

In a small meeting room in the Chamber’s headquarters across the street from Lafayette Square and the White House, Donohue boasts of the organization’s expansion into retail politics.

“If you’re not participating in the political process, if you’re not tying the political process to the policy process, if you’re not out helping candidates advance their interests if they’re the ones you support, then you have far less influence than people who say: ‘This is what we believe, this is what we advocate, and we’ll be there to support you if you share that view with us,'” Donohue says.

Donohue, a 76-year-old Washington veteran who still speaks with the accent of his native Brooklyn, has been president and CEO of the Chamber since 1997. He has developed the group into one of the biggest and most powerful organizations after the Democratic and Republican parties. He has seized opportunities opened by the growing polarization of politics and by campaign finance laws to make his organization a force to be feared and respected come Election Day.

2014 demonstrated just how important the Chamber has become.

It spent $35.4 million, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, mostly supporting Republicans and attacking Democrats. Media reports put the overall amount spent much higher, at above $50 million.

The Chamber was a player in primaries, perhaps most clearly in the bitter fight between the establishment and the Tea Party in the Mississippi Senate race which pitted incumbent Republican Thad Cochran, who’s been in office since the 1970s, and 41-year old Chris McDaniel.

As Cochran entered a primary run-off with McDaniel, the Chamber stepped in to support him, seizing hold of his strategy and guiding him to a turnaround victory. In June, with the run-off heading toward a close finish, the Chamber organized an ad with legendary quarterback Brett Favre, a Mississippi native, endorsing Cochran. Henry Barbour, a GOP heavyweight who ran a pro-Cochran super PAC, credited the Chamber for helping develop the run-off strategy for Cochran, which included appealing to black voters usually outside the GOP’s reach. Cochran eventually won 51 percent to 49 percent.

The Chamber also made a big difference in general elections in swing states that pitted Democrats against more business-friendly Republicans. In North Carolina, it backed state house speaker Thom Tillis over incumbent Democrat Kay Hagan, in a massively expensive race among perhaps the most divided electorate in the country.

The Chamber spent more in the campaign than any other outside group, shelling out $4.4 million to support Tillis and another $1.1 million attacking Hagan. As in the Mississippi primary, it helped develop strategy against Hagan, recruiting retired NASCAR driver Richard Petty, a North Carolina native, to star in a pro-Tillis television spot. Tillis squeaked by with 49 percent of the vote to Hagan’s 47 percent.

Victories such as these give the Chamber bragging rights with the national party committees for Republicans having 54 senators, 245 members in the House, and thus controlling Capitol Hill.

“The Chamber got stronger as it became more active in politics, it got much stronger in the last election when it stepped up and did some very decisive things that I think people thought we’d never do. The only message to that is we’re just getting started,” Donohue says. He declines to offer an estimate of how much the Chamber might spend on elections in the 2016 cycle, but hints it will be more than ever.

It won’t merely give money to candidates and ads,but will burrow deeper into other rich electioneering soil. Donohue says that includes get-out-the-vote efforts, which historically have been hugely successful for labor unions supporting Democrats.

“Unfortunately, a lot of people when they look at the election, they look at one index — how much are people spending on ads,” Donohue complains. “That comes from a business mentality, I think, that says: ‘We want to sell popcorn, we oughta have ads on popcorn on TV.’ Well, there’s a lot of ways to sell popcorn, and they’re not all on TV.”

Competition for influence grows

Taking all of its political activities into account, the Chamber is one of the most powerful groups in U.S. politics.

“I would say it’s the biggest business group without question,” says Bill Allison, senior fellow at the Sunlight Foundation, a nonprofit organization that advocates for transparency in government.

Allison, an expert on political influence, judges the Chamber’s influence greater than that of other outside groups on the Right.

But those other groups also have clout, and some of those conservative factions have goals at odds with the Chamber’s.

Chief among them is the network of organizations supported by billionaire industrialists Charles and David Koch, which is growing even faster than the Chamber.

The Koch brothers, bogeymen of the Left, are not interested in a governing center. They want to move the center to the right. They’re ideological libertarians, as demonstrated by their willingness to take on business-friendly Republicans.

Forbes magazine estimates the Koch’s net worth at $43 billion apiece. They hope to raise and spend nearly $900 million through their network in the run-up to the 2016 elections, the Washington Post reported this year.

That sum includes spending on some items not related to the elections, such as think tanks backed by the network. It also counts spending by donors other than the Koch brothers.

Nevertheless, the total is on the scale anticipated to be spent by the Republican and Democratic candidates for president. Hillary Clinton, for example, reportedly aims to raise $2 billion to win the White House, and Republicans aim to gain a similar amount for their candidate.

The main vehicle for the Koch network is the Freedom Partners Chamber of Commerce, a tax-exempt 501(c)(6) organization, the same tax structure used by the U.S. Chamber. Freedom Partners was formed in 2011 and can take advantage of the campaign finance rules that, since the 2010 Citizens United decision, allow chambers and trade associations to spend unlimited sums without disclosing their donors identities.

For the time being, the Chamber, Koch-backed groups and other conservative groups such as the Club for Growth and Heritage Action are mostly on the same page. But there are unmistakable fault lines between business and the energized right wing of the GOP.

“We are not going to go out there and lobby for a special benefit for any one member of Freedom Partners,” says Andy Koenig, a senior policy adviser for Freedom Partners. “We are trying to level the playing field. We’re a newer organization, but we’re getting started and we’re going to be around and we’re going to be consistent on this message.”

Most of the time, the Chamber and Freedom Partners work together, Koenig says. But Freedom Partners opposes what it calls “corporate welfare:” Subsidies or rules that benefit individual companies or industries.

Ex-Im Bank in the crosshairs

One of the conservative groups’ targets is the Export-Import Bank, which they consider a fountainhead of corporate welfare. This puts them 180 degrees at odds with the Chamber.

The official export credit agency for the United States, Ex-Im, as it is known, is a quasi-governmental bank that provides federally backed loans, guarantees and other forms of credit for U.S. exporters.

It’s now in a fight for its life. Its authorization runs out at the end of June. Conservatives demand it be phased out, noting that a large share of its programs benefit just one company, aircraft maker Boeing.

The bank operated in relative obscurity until recently. It benefits businesses in a wide range of states and congressional districts and has the support of many members of both parties.

But many conservatives want it killed. Their leader is Rep. Jeb Hensarling of Texas, a staunch fiscal conservative and chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, which has jurisdiction over the bank.

The Koch network is dead set against the bank. Despite their generally cordial relationship with the Chamber, they disagree on Ex-Im because “it puts government in the position of picking winners and losers,” says Tim Phillips, president of Americans for Prosperity, the biggest of the Koch-affiliated groups. “And government’s not good at allocating resources.”

The bank’s demise is one of the few free-market priorities that is achievable during the Obama era, Koenig suggests, simply because Congress doesn’t have to do anything to let it die.

“It’s not the biggest issue in the world,” Koenig says, but “we realize that it’s a prime example and pretty low-hanging fruit.”

Ex-Im is only one of many such tensions that will intensify as opposition to big business increasingly becomes a selling point for conservatives who want to tap into populist sentiment.

Immigration policy is another example. Many businesses claim it’s vital to attract high-skilled workers for Silicon Valley and low-skilled immigrants for farms, hotels and restaurants, but a significant portion of the Republican Party disagrees.

Republicans, led by such populists as Sen. Jeff Sessions of Alabama, increasingly bash business to make the case for tighter immigration controls and lower annual immigration.

“The split between who were principled conservatives, on one hand, and business lobbyists on the other wasn’t as pronounced as it’s become since the rise of the Tea Party,” argues Mark Krikorian, executive director of the restrictionist Center for Immigration Studies. In the past few years, he adds, “immigration has joined that list of issues where principled conservatives have grown increasingly, if not hostile, at least skeptical of big business.”

He cites Ex-Im as another example, saying, “That’s one of the major themes of grassroots conservatives: That the corporate interests are not on our side.”

That split defines conflicts over spending on roads and on government in general, which Congress must decide on to avoid a shutdown this year.

Playing defense

Donohue doesn’t want to talk much about the threat posed by the populist Right.

When asked if there has been a permanent shift in attitudes toward business since the 2008 financial crisis and recession, he blame’s Obama rhetoric. The president’s political attacks on the financial system, he said, are something that “this country could pay a serious price for, for a long period of time — until we fix it. ”

He is confident that Republican leaders can steer GOP lawmakers through trouble, avoiding bills that hurt business and the kind of brinksmanship that unsettles corporate planning. Speaker John Boehner “has demonstrated that when the chips are down, he passes what he has to pass,” Donohue says.

Pressed on the rising influence of GOP populists, Donohue redirects the conversation toward Democrats, whose distrust of business is even stronger.

“The same thing, the very same thing’s going on in the Democratic Party,” Donohue says. “Look what’s happening to their one candidate for president. She’s being sucked as far left as you can get,” he says of Hillary Clinton, whose ascendancy to the Democratic nomination is viewed as all but assured.

The Chamber especially notes the rising influence of Elizabeth Warren, Massachusetts senator and outspoken left-winger whose anti-Wall Street diatribes have earned her hero status among liberal activists. She has used that support to push Clinton to embrace priorities such as expanding Social Security.

Donohue warns that the rise of the Warren wing of the Democratic Party is “a dangerous thing.”

“I see it as being a detriment to the Democratic Party that they’re going to wish they never had their hands around,” Donohue says of Warren’s agenda. Later, discussing Democrats’ increasing hostility to Wall Street banks, he adds that he’s “getting sick and tired of some of these people who can’t count past 10 and think they’re an expert on capital formation.”

In December, Donohue floated the idea that the Chamber might get involved in the presidential campaign to respond to the emergence of a Warren-style candidate on either the right or left who would challenge the Chamber’s view of free-enterprise.

Intervening in presidential politics would be a big change for the Chamber, which injects itself into state legislature and gubernatorial races and congressional and Senate elections but sits out presidential races because it has to work with whichever candidate eventually wins.

Donohue says the Chamber will weigh in publicly if a candidate makes “very extraordinary or outlandish comments.”

“We’re worried about somebody that may came out with a proposal that will fundamentally alter our ability to strengthen our economy, or to protect our nation around the world,” he says.

The Chamber, however, would not become engaged in the campaign beyond responding to the proposal, Donohue says.

Going on offense

By becoming a political force at the same time that politics is getting more polarized, the Chamber risks losing its ability to influence the Left.

Labor has seen its influence wane in the Obama era partly because unions are so tied to Democrats that they have little leverage. They cannot credibly threaten to get into bed with Republicans if Democrats don’t do what they want.

“The Chamber’s kind of pushed itself into that corner with Republicans and now with these Tea Party Republicans,” says Allison, the Sunlight Foundation’s influence expert. “Where else does the Chamber go?”

Nevertheless, the Chamber, like the AFL-CIO labor federation and big unions such as the Service Employees International Union, has several built-in advantages over other groups on its side of the partisan divide.

One is that it can exert more influence on individual members by having goals in line with mainstream Republicanism.

“The closer to the party that an organization is, the more impact it will have,” Allison says. Politicians want to get elected, and the most useful political spending is that which goes through their own war chests. Next most useful is money that comes through the official party committees, then leadership PACs, then groups like Karl Rove’s American Crossroads super PAC that is essentially an unofficial arm of the GOP.

Some of the biggest outside conservative groups are significantly further away from individual candidates than the Chamber.

Koch-funded Americans for Prosperity, for instance, is structured as a nonprofit education organization and can aid candidates only much more indirectly than political parties or other outside groups.

In the 2014 North Carolina Senate race, Americans for Prosperity reportedly spent millions aimed at electing Tillis. But its support came in the form of “issue” ads, really attack ads, such as TV spots highlighting Hagan’s support for Obamacare while featuring someone harmed by the law.

While important in determining election outcomes, such aid is not the same as campaign contributions or more direct help.

Another factor playing to the Chamber’s advantage is the massive network of chambers of commerce throughout the country that provide a permanent infrastructure, allowing headquarters insight into unique conditions in different regions and providing a pipeline of candidates. There are roughly 3,000 state and local chambers so most members of Congress have one in their back yard.

Rep. Ken Calvert, a Republican congressman who represents a California district in the Inland Empire, is an example of the Chamber’s institutional closeness with the Republican Party.

Before being elected, Calvert was president of the Corona Chamber of Commerce and remains a loyal proponent of chamber politics.

Calvert says the Chamber reflects the opinion of business in general, “especially small business.”

“Big business can hire their own lobbyists,” he adds, “but small businesses rely on the Chamber.”

Calvert is among a significant number of Republicans who support the Ex-Im Bank and separate themselves from conservatives such as Hensarling. “The Republican Party is not a monolithic bloc,” he says.

There are many in Congress like Calvert. Twenty-five House members voted with the Chamber 100 percent of the time in 2014, and 187 members voted with it more than three-quarters of the time. So did 37 senators, before Republicans took the majority.

In the Chamber’s headquarters, Donohue expresses confidence in prospects for his legislative goals in 2015 and for politics in 2016, despite mounting opposition from left and right.

To succeed, Donohue says, you have to have a firm belief in free enterprise, a strategy, the right personnel, and lastly, “you gotta have the cash to do it.”

On that last point, he’s optimistic. The Chamber, with roughly 450 employees, claims 300,000 member companies, and it represents 3 million companies throughout the entire system of chambers.

The U.S. Chamber has a 97 percent retention rate among member companies with more than $100 million in revenue. Those revenues have grown from roughly $50 million when Donohue started to over a quarter of a billion today, he says.

Donohue represents business, but at times speaks as if his role is bigger than that.

“I really think it’s a time for us to reassess who we are, and what we believe and what we fundamentally stand for, and why have people fought to come to the United States for so long in the search of their dream,” he says, “and we’ve got to put that dream back in place.”