West Virginia Republicans will head to the polls next Tuesday to choose a nominee for their state’s upcoming Senate race. It’s one of the most important primaries in the country: The winner will go up against Joe Manchin, the Senate’s most moderate Democrat, a former governor and the last remaining Democrat inthe (very red) state’s congressional delegation. If Republicans manage to beat Manchin in the fall, they’ll make the Democratic path to 51 seats even tougher by forcing them to take Arizona, Nevada, and at least one very red state (like Texas or Tennessee).

So who are the Republicans going to pick? And why does the GOP have such a crowded field (one that includes a congressman, the state’s attorney general, and a criminal) in a year that might end with a Democratic wave?

Here a quick explanation:

The Basics: We Don’t Know Who Will Win The GOP Primary

There are three major candidates in this race—Evan Jenkins (a congressman who currently represents the rural, coal producing 3rd District and who, like many West Virginians, used to be a Democrat), Patrick Morrisey (the state’s attorney general and a favorite of ideological conservatives), and Don Blankenship (a mining executive who recently spent time behind bars for his role in the Upper Big Branch Mine Disaster).

And nobody knows who is going to win.

There’s almost no polling. Fox News has fielded the only public poll of this race, and it put Jenkins ahead of Morrisey and Blankenship, each getting 25, 21 and 16 percent of the vote respectively. That’s a good sign for Jenkins—it’s always better to be ahead in polls than to be behind —but it’s not a guarantee. It’s just one poll and almost 40 percent of respondents were either undecided or voting for one of the lesser-known candidates. Jenkins is ahead, but one poll simply isn’t enough to make a confident projection.

And past presidential primary results don’t give us much of a clue either. In 2016, Donald Trump won the state by an overwhelming margin, but that doesn’t tell us much. Trump became the presumptive Republican presidential nominee a week before West Virginia voted (Ted Cruz and John Kasich dropped out after losing to Trump in Indiana). And while Trump likely would have won big in West Virginia anyways (it’s a mostly white, blue-collar state and Trump did well with those voters in other primaries), it’s hard to infer much from the fact that Trump won a one man race there. Mitt Romney had also more or less wrapped up the GOP presidential nomination by the time the state’s primary rolled around in 2012. So that doesn’t tell us much either.

Maybe once the results start to roll in, we’ll be able to see similarities between this primary and some other state-level GOP primary. But, as others have pointed out, the state-level Republican Party in West Virginia has changed quickly and it’s tough to gauge exactly what the shape, size and preferences of the electorate will be.

The Bigger Picture: Why the Republicans Have a Strong Bench Now

But even if we can’t confidently predict who will win the primary, it’s worth asking: Why is this primary different from past races? Specifically, why does the West Virginia Republican Party suddenly have such high-quality recruits (former representative and current Senator Shelly Moore Capito in 2014, as well as Jenkins and Morrisey this cycle) when they struggled to run solid candidates for much the last half-century?

To understand exactly why, we need to zoom out and take a longer view of West Virginia political history. (Note: Last year I wrote an analysis of this race that makes some similar arguments but focuses on the general election. Read more here.)

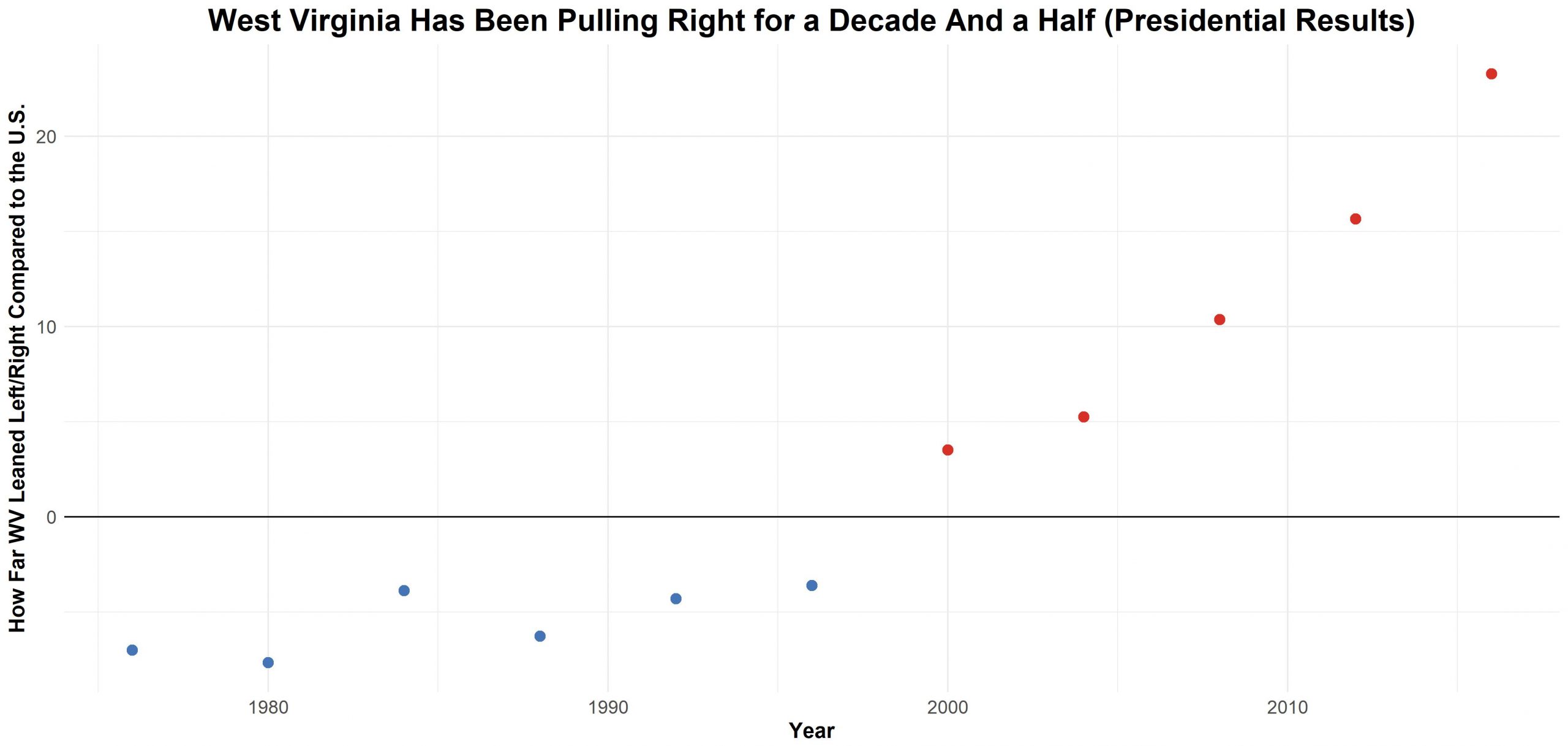

This graphic shows the difference between the Republican share of the two-party vote in West Virginia and the country over time—if a point is above the line, it means West Virginia was to the right of the nation that year, and points below the line indicate years when West Virginia was to the left of the country as a whole. The graphic starts in 1976, when Jimmy Carter eked out a win over incumbent Republican President Gerald Ford. At that time, West Virginia was significantly more Democratic than the country as a whole. It voted against Ronald Reagan in 1980 and then-Vice President George H.W. Bush in 1988 despite both men winning landslide victories.

But in 2000, when George W. Bush ran against then-Vice President Al Gore, the state jumped rightward. Bush narrowly lost the popular vote in 2000, but he won West Virginia by 6.3 points (red dots indicate years where the GOP performed better in West Virginia than they did in the national popular vote). And in every election since 2000, the Mountain State has taken another step right.

Some of this shift can be attributed to cultural factors. As the Democratic Party has moved left culturally (think of the difference between the presidential campaigns of Bill and Hillary Clinton), they’ve had less appeal to the sort of white, blue collar voter that’s common in the Mountain State. At the same time, the GOP moved to the right culturally (think of the difference between George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush, or the stylistic differences between Mitt Romney and Donald Trump), which allowed them to pick up votes. There are numerous other factors (like the GOP’s pro-coal stance) that contributed to the state’s rightward shift, but the key point here is that the trend didn’t revolve entirely around either Barack Obama or Donald Trump.

These more recent presidential results have given West Virginia Republicans reason to be optimistic about their chances on the state level for almost two decades. But the GOP only recently started winning these other offices.

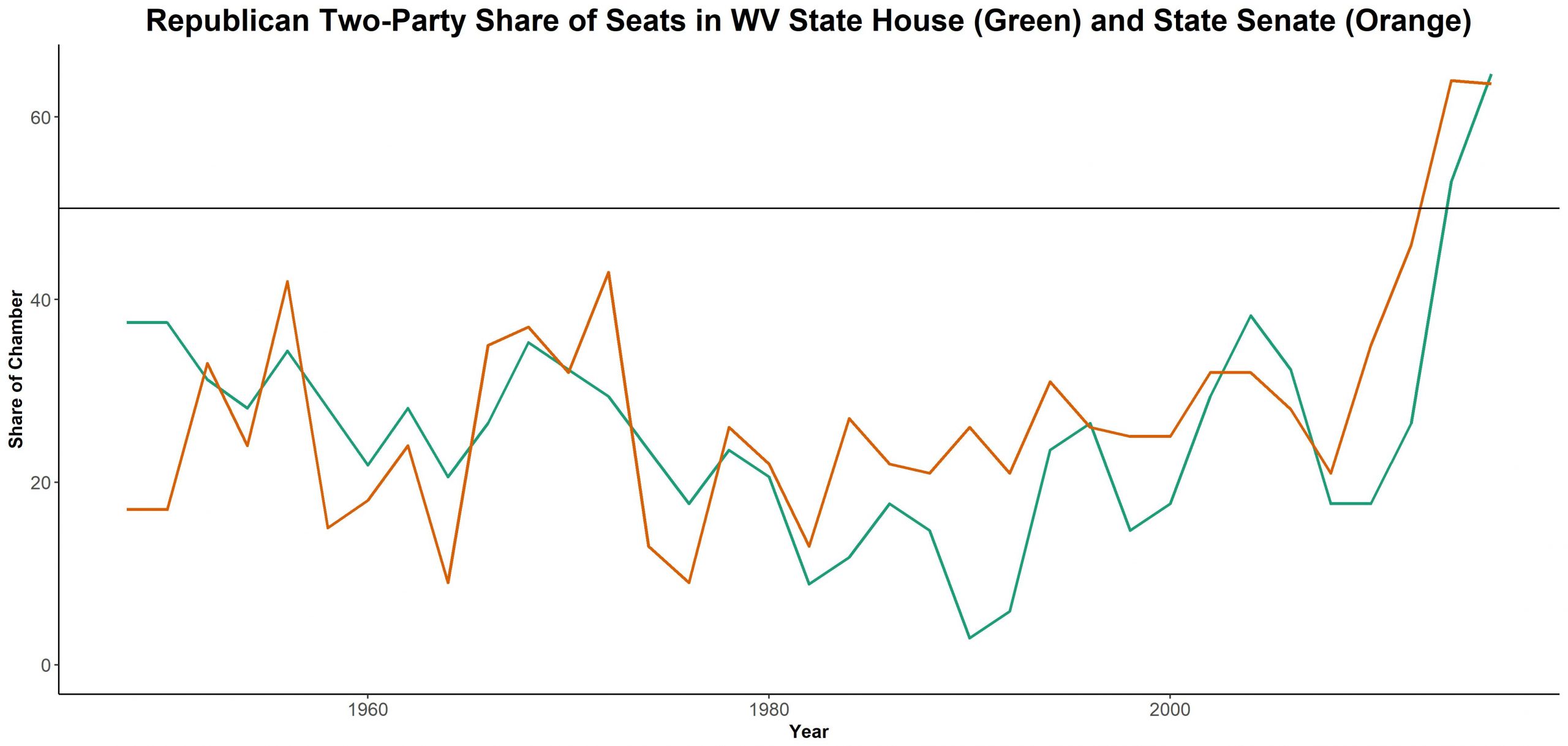

This graphic shows the percentage of seats in the state Senate and state House of Delegates held by Republicans over time since 1948 (data was taken from National Council of State Legislatures and Michael Dubin). Despite the political ups and downs of that era (which included landslide wins by both parties) Democrats often won 60 percent or more of the seats in each chamber. The state had been shifting rightward on the presidential level since 2000, but the GOP had a tough time making a dent in the state houses until the middle of the Obama Era.

This pattern shows up in other races too. Republican David McKinley didn’t take the 1st Congressional District (my home district, the northern part of the state) until 2010. In 2014, Shelley Moore Capito became the state’s first Republican senator since the 1950s, and Democrats managed to hold onto the third district (coal country) until 2014, when Jenkins unseated Democratic Rep. Nick Rahall. Patrick Morrisey is the state’s first Republican Attorney General since the 1930s.

Put simply, national Republicans only started making inroads into West Virginia in the last decade or two. And while state-level Democrats were able to put distance between themselves and national Democrats in the 2000s, they haven’t been able to do that for the last eight to ten years – allowing the GOP to gain more seats and build a strong bench.

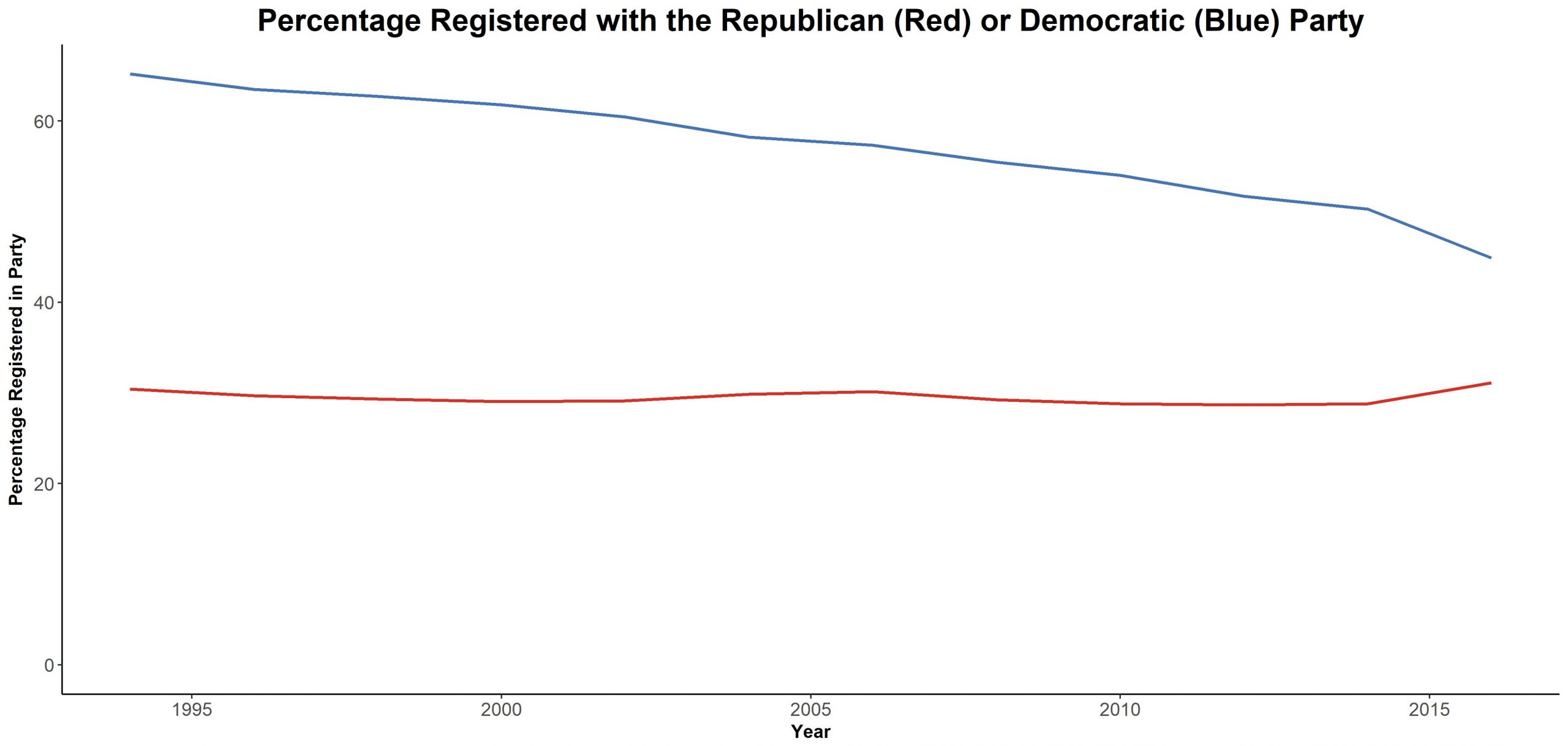

This strong bench doesn’t translate into a guaranteed GOP win in 2018. As FiveThirtyEight’s Clare Malone recently noted, Democratic registration has been falling but Republican registration hasn’t grown.

This shows party registration data from 1994 to 2014 at roughly two-year intervals (as close to the elections as I could get) in West Virginia. If Manchin manages to perform well with former Democrats who moved to the GOP before and during the Trump era (which appears to be part of what happened in Pennsylvania’s 18th District in March), he could win. He has a strong record of wins and major handicappers mostly see it as a 50-50 proposition. RealClearPolitics, Cook Political Report and Inside Election all rate the race as a toss-up Sabato’s Crystal Ball has it at only “Leans Democratic.”

Moreover, if Republicans nominate Blankenship they could effectively throw the race. Blankenship seems like he might be much worse than your run-of-the-mill bad candidate. There’s a difference between the performance of someone like Sharon Angle and someone like Roy Moore or Joe Arpaio. If Blankenship wins the nomination, he’ll could easily end up in the latter group. But if Republicans nominate Jenkins or Morrisey, West Virginia could one the most interesting, competitive races in the country.