The weapons lobby has been waiting for this moment a long time. After years battling to defend their shrinking slice of the sequestered budget pie, defense contractors are going on offense to get what they can from the next defense budget with more money in it than planned.

The two-year deal reached by lawmakers on Capitol Hill loosened the fiscal chains that have restrained defense spending since 2013. Analysts say the deal is good news for the Pentagon not only because it provides more money, but also because it avoids the uncertainty of continuing resolutions for fiscal years 2016 and 2017.

Defense lobbyists point out that sequestration isn’t really over, just softened for two years. After that, its across-the-board cuts snap back automatically unless lawmakers can reach another agreement to forestall them in fiscal 2018.

And even without sequestration, the military says it needs more than it is going to get — about $5 billion less than the president’s 2016 fiscal request. For fiscal 2017, that shortfall increases to $15 billion.

So lobbyists still have their work cut out for them.

Going on the offensive

Some say the deal changes the lobbying landscape. “You have the ability to flip the switch from defending programs and defending existing dollars to going on offense,” said Marc Numedahl, vice president of Capitol Strategies Partners. “You know there’s a two-year window where program offices have money and will be spending, and hopefully will be spending at a higher rate.”

The budget deal will also allow the Pentagon to launch new projects that continuing resolutions, by holding spending at the previous year’s level, prevented getting off the ground.

The Pentagon can now award more lower-value contracts, Numedahl says. When the budget shrinks, the Defense Department fights to “protect the big new shiny program” and leaves smaller purchases to languish.

“I think giving budget stability and increasing the budget will allow for secondary or tertiary priorities to be met,” he says.

The fiscal 2016 appropriations bill is tied up with the omnibus spending budget that lawmakers must pass by Dec. 11 to prevent a government from shutdown. It won’t be clear what the Pentagon is requesting for fiscal 2017 until early next year, but the “wish list” it released in March provides a glimpse into the types of programs it says it needs but normally doesn’t expect to get. Those include new programs, improvements to sensors and more training and simulators to increase readiness.

Some services provided specific programs they need to decrease the risk under which they operate. The leader of the Navy said in March that some of his top priorities are buying 170 more upgrade kits to protect air-to-air radio frequencies, purchasing additional sensors that can be towed undersea by submarines and buying more Boeing F/A-18F Super Hornets and Lockheed Martin F-35C joint strike fighters to fill the gap as legacy fighters reach the end of their usable life.

Acquisition of the F-35, the most expensive program ever undertaken by the Pentagon, is expected to cost $400 billion for about 2,500 planes, though lawmakers said they expected that number to ultimately shrink because of “prohibitive” costs.

The former commandant of the Marine Corps said he would invest any additional money in home-station readiness, modernization and quality-of-life programs for Marines, all of which have slipped as the service was forced to focus all of its money to prepare and support forward-deployed forces.

Analysts said there are certainly programs that will benefit from the boost in spending, but that the Pentagon is less concerned with long-term programmatic buys than increasing readiness because of the risks posed by the Islamic State and Russia.

Nora Bensahel, a distinguished scholar in residence at American University, said current events are changing the calculation. Budget priorities were different four years ago and the Pentagon may have decided to use the money to invest in things that need a long lead time and will pay off in the future, like weapons systems or airplanes, while leaving the services open to more risk today, she said.

The military says it needs $5 billion more than what it will get in fiscal 2016. AP PHOTO

The state of the world, however, has shifted the Pentagon’s focus to buying back readiness that was lost under sequestration to be prepared in the near-term.

“I think there is a sense that the world is a dangerous place and that crises can erupt unexpectedly, so maintaining that readiness is going to be important,” she said.

Bensahel said she expects to see the Pentagon spend more on training centers and live-fire exercises to better prepare forces to fight.

Analysts are also careful to point out that what many are calling extra money still represents a cut from the president’s request for the Pentagon. Jacob Cohn, a senior analyst with the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, said an increased budget does not mean more procurement and that modernization is more likely to be truncated than expanded.

Still, the Pentagon has several big-ticket items for which bills are coming due — the F-35, Northrop Grumman’s long-range strike bomber, Gerald R. Ford-class aircraft carriers built by Huntington Ingalls Industries and the replacement for the Navy’s Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines, which will be built under a work-sharing plan by General Dynamics Electric Boat and Newport News Shipbuilding, a division of Huntington Ingalls.

The Pentagon has struggled mightily over how to pay for these expensive items, any one of which could hog a single service’s budget and prevent other purchases and modernization. One solution bruited about is to create a separate procurement budget for specific projects. Another is to share the costs between different agencies that would use the weapons.

Dan Stohr, communications director for the Aerospace Industries Association, says money for these big-ticket items may “work differently,” but the budget deal does not get down to the program-level, so it’s still unclear how the Pentagon will divide up the costs.

Still, he acknowledges, the deal will make it easier for the Pentagon and Congress to pay for what they want most.

“It does allow for a good deal of additional flexibility, and allows for more strategic thinking about how things will be applied to different programs, but that all still has to be worked out,” he says.

Mike McCord, comptroller of the Pentagon, said last week that the Defense Department doesn’t have an answer for how to pay for replacements for Ohio-class submarines, which is due to begin in 2021. The Navy protests that this program will gobble up its shipbuilding budget.

“The Navy has expressed a lot of concern and said, until you can prove to me it’s not going to come out of my shipbuilding budget, then I’m going to keep waving my arms around until somebody notices my problem and tells me how we’re going to solve it,” McCord said during a discussion at the Center for Strategic and International Studies on Nov. 30. “Right now, it’s probably not in our power to tell them how it’s going to be solved.”

The Navy is planning to buy a dozen of the new subs at a cost of about $100 billion, according to reports. The existing fleet of Ohio-class submarines is set to retire at about one per year beginning in 2027.

The Pentagon faces another big bill because of the “once-a-generation” need to rebuild the nuclear triad, McCord said. The triad refers to nuclear weapons launched from sea, land and air.

The existing fleet of Ohio-class submarines is set to retire at about one per year beginning in 2027. NAVY PHOTO

While the replacement for the Ohio-class boomers are one piece of that, leaders have stressed that modernizing the country’s Air Force bombers and silo-launched intercontinental ballistic missiles are also a priority for all services.

“We’re all sailors here and we think and talk about the Ohio, but right after the Ohio is the B-2 bomber and that needs [to be] modernized. It’s time, it’s decades old. Right around that time the ICBMs out there, those processes and those networks, they need to be upgraded,” former Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Jon Greenert said in August.

The Air Force awarded a contract to Northrop Grumman this fall to build the next generation long-range strike bomber as older bombers reach the end of their service life, though beginning work is delayed as the losing bidder, a team of Lockheed Martin and Boeing, protests the contract award.

The Air Force plans to buy 100 of the bombers, which will cost at least $550 million per plane.

Lobbying is always ‘subjective’

Other lobbyists say the budget deal hasn’t changed their modus operandi. Kraig Siracuse, managing director of Park Strategies, says that because the climate on Capitol Hill is constantly evolving, the budget deal is no different from past deals.

“Lobbying and how you deal with Congress is subjective, it changes every year,” Siracuse said. “If you understand the process, you understand how to help your clients.”

Tighter budgets make it harder to pay for bad projects, which is a good thing, he points out, but high quality weaponry that is really needed will make it through regardless of the budget, he said.

“Has lobbying gotten harder because of [sequestration]? Not really, because that’s a top-line number,” he said. “What’s more important is if DoD or Congress wants or needs it … good projects needed by soldiers in the field are still paid for. The DoD budget is still a big number.”

This view is echoed in some congressional offices. “In the defense arena, the most proficient and respected lobbyists are always going to be advocates for their interests, but they know in the end that members are going to do what they think is right and what they consider to be in the nation’s interests,” said Joe Kasper, a spokesman for Rep. Duncan Hunter, R-Calif. “They usually involve feeling someone out, and addressing any concerns or questions, and that happens regularly, whether in passing or a more organized way.

“The real [beneficiaries] of a longer budget deal are the men and women of the military, because the Pentagon can now start planning with some certainty, and that’s good for everyone — Congress, included,” he added.

But there is also a sense that the budget deal allows the defense sector to approach Congress more aggressively. “I think a two-year budget deal will change a lot of the approaches to how you petition Congress, how you work and so forth,” said Sen. Richard Shelby, R-Ala., and a member of the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Defense. “You have more certainty, you have not quite as much bickering, I think that’s good for Congress.”

While individual lobbying firms have focused on promoting their clients’ projects, the Aerospace Industries Association has taken the lead in lobbying against sequestration as a whole, trying to persuade members that across-the-board cuts have badly delayed long-term modernization.

Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Defense member Sen. Richard Shelby, R-Ala., says a long-term budget deal can determine how aggressive defense lobbyists will be. AP PHOTO

That problem “hasn’t gone away at all,” Stohr said. So the association isn’t easing off its pressure for higher spending.

“These are short-term deals,” Stohr said, “We get a little bit of budget certainty for two years, then the process starts all over again.”

Still, he said, the deal was probably the best that defense contractors could hope for realistically.

“Would we like threat of sequestration removed all together? Absolutely. But you take what you can get and then you move on to the next fight,” he said.

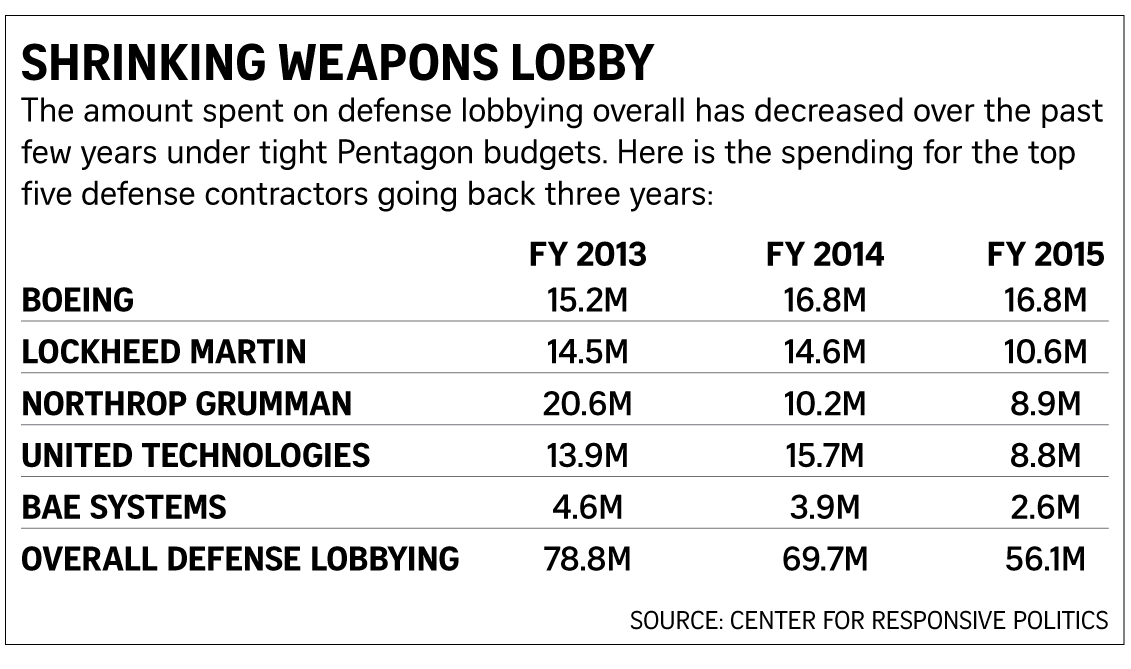

Lobbying spending has fallen from $78.8 million in fiscal 2013 to $56.1 million in fiscal 2015, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. Four of the five biggest defense companies also cut lobbying spending in fiscal 2015. Boeing, the only company not to cut, held its spending at $16.8 million.

One defense lobbyist predicted that spending on lobbying would continue to fall until the next big fight over a weapons system.

“I think the downward trend will continue in the short run … but in a year or two, it will level off because of budget numbers,” the lobbyist said, “and that can always change if there’s a major fight that year, like the Joint Strike Fighter or [Northrop Grumman] Global Hawk.”

The decline is due more to America’s reduced presence in the Middle East than to budget uncertainty, Siracuse said, adding, “It probably has more to do with war and people’s perceptions that there’s stability in Iraq and Afghanistan, fewer soldiers [deployed] and the amount DoD will spend will go down.”

What it means for the Pentagon

One thing the budget deal is likely to change is the timing for the passage of defense bills, because the Pentagon already has its headline number for fiscal 2017. So Siracuse expects Congress to get defense appropriations done much earlier, rather than in November or December, which has been the norm recently.

“The timeline for final passage of the defense bill is probably shorter, closer to the end of the fiscal year. Congress will look to pass all the appropriations bills on time, so it will be important to talk to members and staff sooner in the process,” he said.

“Members of Congress, leaders at Pentagon … can actually go back to doing their jobs now,” said another lobbyist. “Congress can do oversight … focus on larger issues and aren’t bogged down by constant background of a budgetary fight.”

McCord said the budget deal is a step in the right direction but does not fund the department or prevent a government shutdown. Congress still needs to pass omnibus appropriations bills.

“We can’t spend a framework, as important as a framework is,” he notes.

The department will be about $15 billion short of what it says it needs for fiscal 2017, McCord said. To make ends meet, McCord expects “slowdowns in some modernizations,” but he did not specify which programs may be affected.

The fiscal 2016 appropriations bill is tied up with the omnibus spending budget that lawmakers must pass by Dec. 11 to prevent a government from shutdown. AP PHOTO

Beyond 2017, there are no hard numbers for Pentagon brass to use for planning, although the pattern has been for appropriations to come in about halfway between the president’s request and the sequestration level.

Adding to uncertainty is that there will be a new president in 2017. And if it’s one of the Republicans, campaign rhetoric points to major increases.

The new, higher starting numbers for the next two fiscal years will put the Pentagon in a good position to negotiate for 2018, though even if sequestration cuts come back in full force, which has never been allowed to happen, the budget would essentially flat line between fiscal 2017 and fiscal 2018.

Lawmakers have always been able to reach a budget deal to prevent the Pentagon from feeling the brunt of sequestration’s cuts. This third short-term fix provides hope that Congress will find a solution to raise the caps through fiscal 2021, when the decade of cuts ends.

“It’s reasonable to expect another budget deal in fall 2017, but nothing is guaranteed,” McCord said.