For the last few weeks, I’ve been trying to stay away from Texas. It’s been over-covered and heavily polled, so I’ve tried to shed light on other key races such as Arizona, Tennessee, Wisconsin, Indiana and more. But despite the best efforts of wonky political types, Texas Senate seems to still be far-and-away the most closely watched race of 2018.

So I wanted to venture back into the numbers one more time to (1) argue that Republican Sen. Ted Cruz is still ahead and has been ahead this whole time; (2) show that the numbers in Texas are a lot more normal and generic than you might think; and (3) think a little bit about why political junkies have paid so much attention to Texas this cycle.

Cruz is (Still) The Favorite

A lot of the reporting about Texas has had sort of a weird, jump-y feel—that is, that Texas is either treated as a total toss-up or as an obvious win for Cruz. But the data tells a more nuanced story.

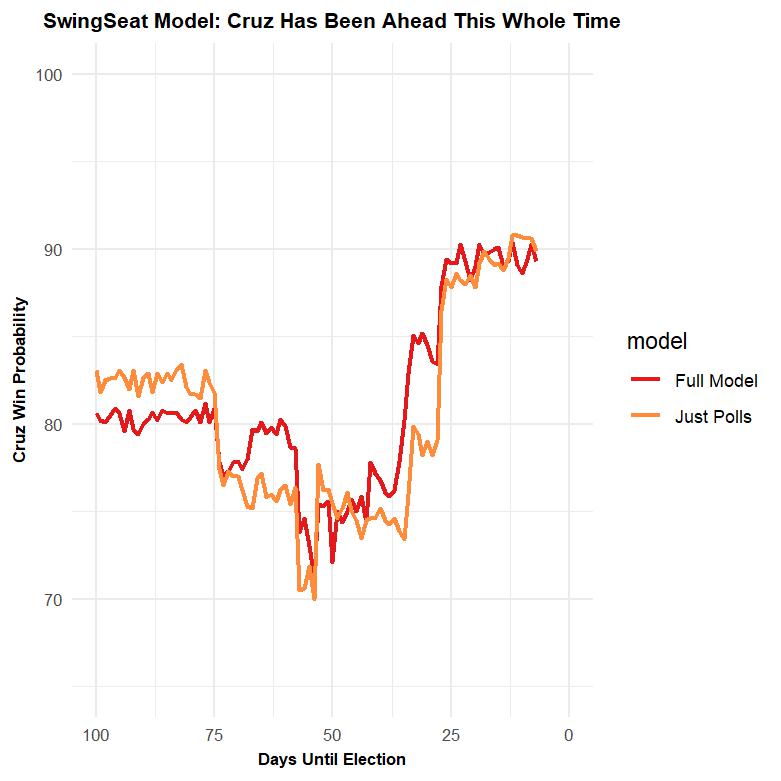

This graphic shows the win probability for two different versions of THE WEEKLY STANDARD’s stats-driven Senate forecast (a.k.a. SwingSeat) over the last three months. One line is the official SwingSeat model (the “full” model), and it uses polls and other factors (e.g. incumbency, past election results, etc.) to generate daily win probabilities. The other line is an older forecast that relies basically only on the polls.

And the graphic tells a relatively simple story. Cruz has led in the polls for months. Democratic Rep. Beto O’Rourke got some good polls about two and a half months ago and managed to knock Cruz’s win probability down a bit. But around 35 or so days ago (roughly when the Kavanaugh/Blasey-Ford hearings were happening) Cruz saw an uptick in his win probability. That uptick may be due to Republican enthusiasm around Kavanaugh, or it might have the race heading towards where it naturally should go (i.e. Republicans and Democrats started settling into their partisan camps with O’Rourke unable to get enough swing voters). But whatever the reason, Cruz’s win probability has increased and he’s now a strong (but not unbeatable) favorite to win the race.

Other forecasts are less bullish on Cruz than SwingSeat is, but they all basically agree that Cruz has a solid but not unbeatable lead.

Answering this “who’s ahead, who’s behind” question clearly is important because the race has been hyped up and it’d be easy to get the wrong impression. But the more interesting question in my mind is why the race is where it is. And the surprising answer might be that Things Are Actually Normal.

The Race Is More Normal Than You Think

If the polls are right about this race (and that’s an “if” I’m going to come back to), then Cruz and O’Rourke may both be a bit more generic than they’re commonly believed to be.

Here’s a simple, forecast-free way of thinking about it: Trump won Texas by 9 points in 2016 while losing the national popular vote by 2 points; Romney won Texas by 16 points while losing the overall popular vote by 4 points. That means that Texas’s baseline partisanship is probably around 13 to 15 points more Republican than the nation. If we were to subtract out a penalty for Trump’s unpopularity (make it about 8 points—roughly the amount that Democrats lead by on the generic ballot) and give Cruz a good but not enormous bonus for being an incumbent (because it’s tougher for big state representatives to make a personal connection with so many constituents) we end up guessing that Cruz would win by high single or low double digits. That’s only a couple points better than how Cruz is actually doing in the RCP average—which currently puts him ahead by 7 points.

Moreover, if you dig into the statewide favorable/unfavorable numbers on each candidate, neither of them stand out. Cruz’s net favorability was +7, +10, +8, +9 and +4 in recent polls by UT, CNN, Quinnipiac, Siena and Emerson respectively. In those same polls, O’Rourke’s net favorability was often close to or lower than Cruz’s favorability: -5, +6, -2, -3, +12 in those same surveys. This comparison isn’t a perfect, all-encompassing picture of public opinion (e.g. I didn’t look back at every poll of this race, some might prefer the favorability rating for all adults rather than likely voters, I don’t have a breakdown of strong/somewhat favorability, etc.). But these numbers don’t really match the media narratives. Likely voters in Texas don’t universally loathe Cruz or gaze adoringly at O’Rourke all day. The numbers suggest that voters view them in at least a semi-normal way.

Put simply, the current state of the race isn’t so far off what we’d expect from a normal, run-of-the-mill Texas election where an incumbent Republican runs against a good-but-not-shockingly-great Democratic candidate in a midterm where Democrats lead by a solid margin in the generic ballot.

Now there’s an obvious (and truly important) caveat here: the polls could be wrong. If O’Rourke outperforms the polls and either comes close or wins the election on Tuesday, then we’ll know that he was a much-better-than-replacement-level candidate. Results trump polls.

But we don’t know that the polls will be off in O’Rourke’s favor. Maybe the polls will be accurate. Or maybe Cruz will outperform the polls and win by a big margin, pushing O’Rourke into (at least temporary) irrelevance. It’s simply hard to know if the polls are going to be off or which candidate they might underestimate.

And until we get more information (either from polls or results) it’s okay to think that the polls are probably decent and that this race is a lot less exceptional than it’s been made out to be.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Texas

Despite this persistent Cruz advantage in this relatively normal election, the Texas Senate race has received a tremendous amount of media attention. There are some good reasons for this: Republicans usually win high-profile races in Texas, and the fact that O’Rourke has a chance (especially considering his liberal views on various issues) is newsworthy. O’Rourke has also raised a truly enormous amount of money, and Texas has Romney-Clinton voters (as well as other types of voters) who are worth watching.

But I suspect that part of the intense energy around Texas is really about ideas about the future—both short-term and long-term.

The relationship between O’Rourke and the short-term Democratic future is obvious. Trump, who in some ways resembles a cartoonish-ly exaggerated version of Democratic criticisms of the GOP, is in power and the Republicans run both houses of Congress. It’s a very natural, human thing to look for some sort of challenger or alternative when you’re out of power. And with about six months to go before big name candidates announce presidential runs, O’Rourke was able to step into that space relatively easily and be a sort of locus of Democratic hopes.

But I think there’s something going on with the long-term future as well. I think that a lot of people (especially in the world of commentary and analysis on both sides) consciously or unconsciously think of Texas and California as possible futures for America. They both already contain sizeable Hispanic populations (a group that’s been growing nationally) and both states are reasonably urbanized. So it’s easy to look at them and assume that at least one of them reflects the future. And if both go blue, the implication is that the future will inevitably be Democratic.

And I think that possibility—that Texas will go blue and that that will tell us something meaningful about our long-term political future—is what drives some of the intensity around this race.

And I tend to think that intensity is a misplaced. Texas isn’t guaranteed to go blue (this cycle or in the future), and there are lots of good reasons to think that Texas isn’t a perfect representation of the future of U.S. politics.

As I’ve argued before, Texas hasn’t been trending left (as is the conventional wisdom in certain circles) as the Hispanic population has grown. The state has moved right in the medium-to-long term and only went light red in 2016, when Donald Trump lost ground among traditionally Republican college-educated white suburbanites. O’Rourke could theoretically win an upset by building on those gains—but one win doesn’t change the color of a state. In 2020, political conditions may end up favoring Republicans, and Trump or some future GOP presidential candidate might find a way to win those swing-y college-educated suburbanites back and replicate stronger Bush and Obama era GOP margins in the state. Moreover, Texas’s growing Hispanic population might not lead to the windfall gains that some Democrats expect—Texas Hispanics tend to vote for Democrats, but they were less Democratic than Hispanics were overall in both 2016 and 2012.

And Texas is far from a perfect reflection of the current or future United States.

The Lone Start State is, despite the stereotypes about cowboys and the pictures painted by Friday Night Lights, much more urban than the rest of the country. The larger Dallas, Houston, and Austin areas cast about two thirds of the major party presidential votes in 2016—meaning the megalopolis has significantly more power in Texas than in much of the rest of the country, and that it’s more vulnerable to lurching left if the urban-rural divide widens.

But it’s not immediately clear to me that the rest of the country is about to become as urban as Texas. Over the last few decades, smaller cities and large towns have in the aggregate grown about as quickly as the American megalopolis has grown in the aggregate (this is probably the most interesting piece of political data point I’ve seen in years—I wrote more about it here). If that trend keeps up (and it may or may not) then Texas’s trajectory (which involves multiple fast-growing megalopolises) might diverge from that of the nation as a whole (where large towns and cities of various sizes in the aggregate retain relatively stable levels of political power).

It’s also almost impossible for any one state to fully encapsulate the national trend because voting patterns vary across regions. Trump’s margin among blue-collar white voters was not identical in Florida, Iowa, Texas, Georgia, and Arizona. Clinton’s margin among Hispanics was lower in Texas than it was in Arizona. A lot of factors (including religion, income, and more) figure into these differences, but region has a long history of having an influence in American elections. So it’s hard for any state—Texas, California, wherever—to meaningfully encapsulate the present or future of the country simply because every state is fixed in a region.

I could list more examples, but I think the gist of my argument is clear: Even if Texas were to go blue (and there’s a lot of reason to be uncertain about that trajectory), that wouldn’t mean that the nation would inevitably become solidly Democratic. Texas is, like every state, a unique place. And no matter how hard we try to examine a single election (even an election as overly-examined as this year’s Senate race in Texas) it won’t tell us what’s further down the road politically. American elections tend to remain surprising and competitive—and those are some of the only facts about politics that you can take to the bank.