On Monday, Quinnipiac released a poll showing Senator Ted Cruz ahead by nine points against Democratic Rep. Beto O’Rourke in Texas. Before that, Emerson College released a poll that had Cruz up by only one point, and Marist published a survey showing him ahead by four. Those aren’t perfect numbers for a Republican in Texas.

In 2016, Donald Trump won Texas by nine points—a comparatively low point for Republicans, considering that Mitt Romney, John McCain, and George W. Bush won the state by 16, 12, and 23 point margins in 2012, 2008, and 2004, respectively. Moreover, Republicans have won every Senate and governor’s race in the state since 1994, often by solid margins.

So what’s going on? Is Ted Cruz really in danger of losing his seat? And if Cruz loses, in Texas, what does that mean for the parties more broadly?

The Math: What Do Forecasts and Polls Say?

THE WEEKLY STANDARD’s Senate forecast, SwingSeat, thinks that Cruz is a solid but not unbeatable favorite in this race. It looked at current polling and “fundamentals” (like past election results and presidential approval) and thinks that Cruz’s re-election odds are around 6 to 1 or 7 to 1. That probably translates to rating the race as “Likely Republican”: Cruz is a real favorite, but O’Rourke still has a shot.

SwingSeat is more bullish on Cruz that other estimates, but other approaches also suggest that Cruz has a real advantage. For instance, TWS’s first iteration of the model (which looked almost exclusively at polls rather than a combination of polling and non-polling factors) would have looked at these polls and assigned Cruz roughly 4-to-1 odds of winning re-election. The Decision Desk estimate has Cruz at a roughly 70 percent win probability and the FiveThirtyEight Lite and Deluxe Model have Cruz a little under 4-to-1 odds, though their official forecast puts his odds a little under 3-to-1.

These estimates—which, very roughly, give Cruz somewhere between 3-to-1 and 7-to-1 odds of winning re-election—also pass some basic “sanity checks.” (That’s a math term for doing simple math to make sure your sophisticated methods are outputting sensible answers). In Senate races in which a candidate led the polls by a margin between four points and six points at this point in the election (I’m using the method described here), the leading candidate won a little over 80 percent of the time. You could argue that the probability just be adjusted up (because of Texas’s redness or Cruz’s incumbency) or down (because it’s a midterm year with an unpopular Republican in the White House) but it’s in the same neighborhood as some of the more sophisticated, model-based estimates.

There are some differences between these models. But if you look at them as a group, they’re not wildly different than what the handicappers say, which is that the race is somewhere between “Leans Republican” and “Likely Republican.”

The models suggest that O’Rourke’s chances are roughly between the odds of flipping a fair coin twice and getting heads both times (25 percent) and flipping a fair coin three times and getting heads three times (12.5 percent). Obviously, the odds of that sort of an event are far above zero. It would be foolish to rule out an O’Rourke win. But you also wouldn’t call this race a true toss-up. And that’s roughly where the data says we are in the Texas Senate race.

The History: Is Ted Cruz Just George Allen 2.0?

I’m sure that some readers are mentally protesting at this point, thinking that I’m missing the point and that this race feels like it’s heading in a different direction. Specifically, I’ve seen others compare Texas 2018 to Virginia 2006 – a race where the George Allen, the Republican senator, was supposed to be an early, heavy favorite, but the Democratic candidate (Jim Webb) caught up and eventually won by less than half a point. The implication of this comparison is that Texas will, after an O’Rourke win, permanently pull left. Virginia voted for George W. Bush by eight points in 2004, but Democrats won the state in every presidential and senate race from 2006 to today.

But there are good reasons to think that Cruz isn’t Allen.

In August 2006, Allen was caught on camera calling someone a “macaca.” The comment (and his campaign’s handling of the aftermath) rightly caused Allen to lose ground in the polls. Cruz hasn’t made any comments like this. If Cruz loses, Trump’s unpopularity will likely be the biggest factor. And while George W. Bush’s falling approval rating certainly harmed Allen in 2006, it’s not crazy to think that Allen’s use of slurs ultimately helped tip that race in Webb’s favor.

Moreover, there are other possible comparisons for Cruz. Maybe he’s Bob Corker in 2006, who won a tight race against a tough opponent despite Tennessee’s redness. Maybe Cruz is a Barbara Boxer in 2010: an incumbent in a typically safe state (Boxer was in California) who fought off a tough challenger (Carly Fiorina) in a year that was hostile to Boxer’s/Cruz’s party. Or maybe Cruz will end up looking like Patty Murray, who managed to defend Washington state (a blue state) despite a red wave in 2010.

And Texas in 2018 may not be Virginia in 2006. Texas hasn’t elected a Democrat to statewide office since 1994, while Virginia elected a Democratic governor (Tim Kaine) in 2005, only a year before the 2006 Senate race. The overall partisan trajectory of Texas and Virginia is also different. Virginia started its slide from red to purple in the 1990s. Texas, on the other hand, stayed at a similar level of redness for much of the 2000s and 2010s and only jerked left when Trump entered the political scene. Which all suggests that comparisons between Allen and Cruz are slightly more fraught then they initially appear.

It might seem like I’m losing the forest for the trees here: reducing an argument about momentum to an extremely narrow comparison between two totally different races. But I’m really trying to argue that sometimes the forest is the trees. Details matter in these races, and it does seem like incumbents who are in a similar position to Cruz win more often than they lose. That doesn’t add up to invincibility for Cruz, but it makes him the favorite, just like the models suggest.

Strategy: How 2018 Might Shape 2020

The outcome of this race obviously matters for governance – policy in 2019 and 2020 might look substantively different based on which party controls the Senate. But the Texas race (along with Arizona and Nevada) might also have downstream consequences for political strategy.

Donald Trump won 306 Electoral College votes in the 2016 election (though two faithless electors put his final total at 304). So the simplest Republican strategy in 2020 might be to try to hold the marginal states—keep Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Florida, etc. in the fold and assume that the red states will stay in place, and the easiest Democratic strategy might be to take those states.

But if O’Rourke wins or comes close, Democrats might divert some of their attention from the Midwest to the Southwest.

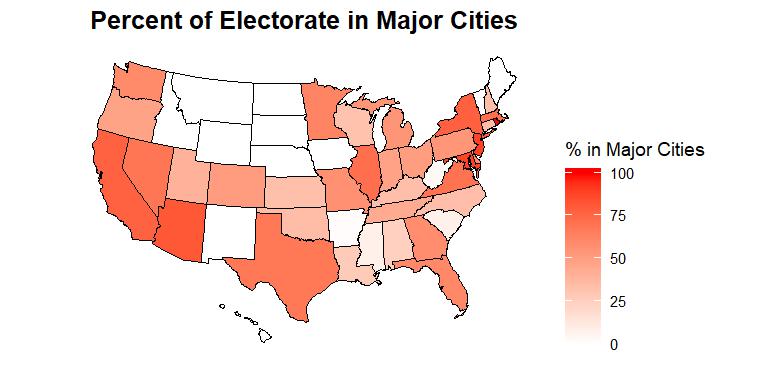

This map shows the percentage of 2016 voters who live in a “large” or “mega” city (definitions here) in each state. In 2016, Republicans made gains in rural areas (often with blue collar whites) that allowed them to take states like Ohio, Iowa, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and ultimately win the Electoral College and hold the Senate. But they lost ground in major metro areas around the country, which hurt them in the Southwest. Trump’s margin was seven points less than Romney’s in Texas, and almost six points lower in Arizona.

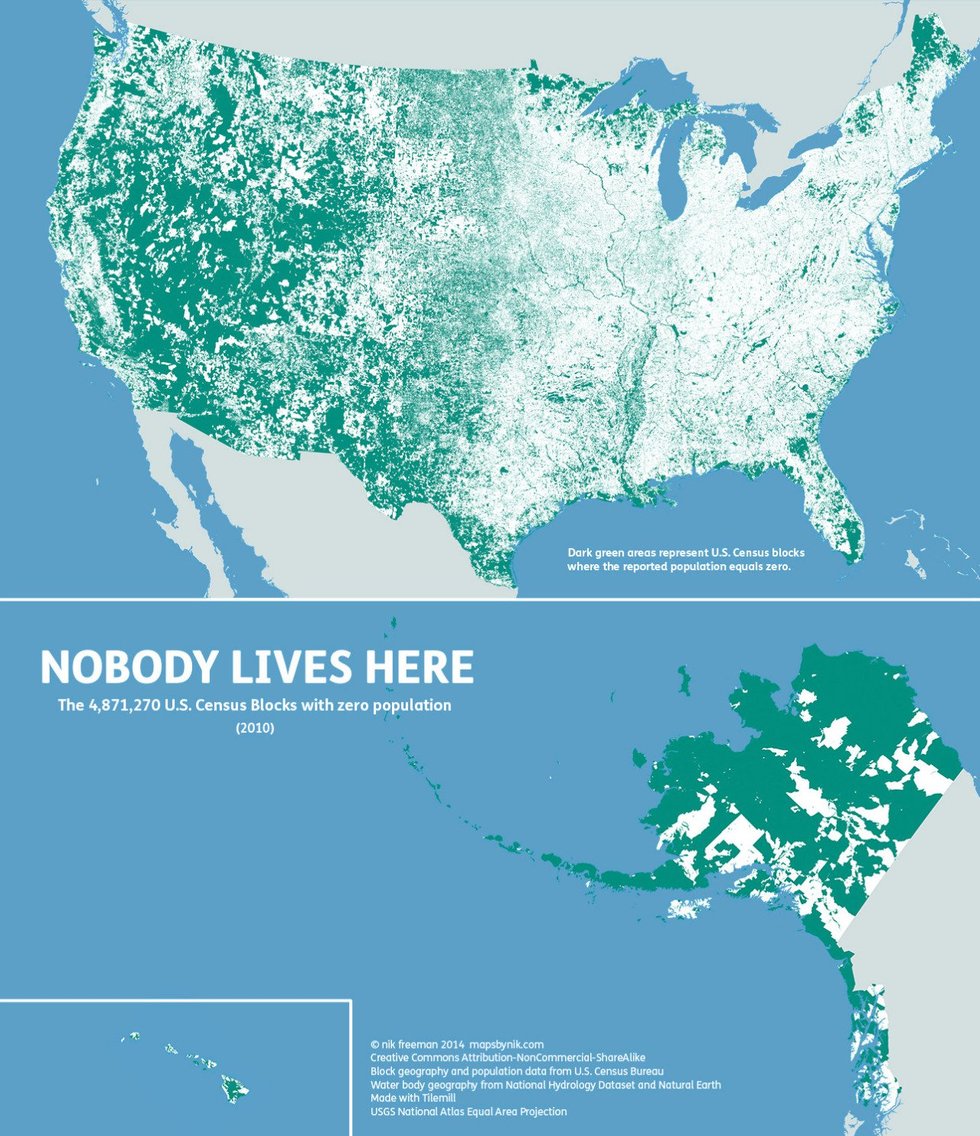

That’s because, contrary to popular imagination about the Southwest, it’s not all cows, cowboys and deserts. Much of the population in Arizona, Nevada, Texas, California and other western states lives in major cities. These states are home to cities like Phoenix, Austin, Houston, Dallas, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, etc. but there aren’t as many reasonably populated small towns or mini cities like there are east of the Mississippi. A lot of the land between major cities is very sparsely populated or empty, which isn’t as true in eastern red states (map is by Nik Freeman).

So if O’Rourke wins or comes close (or if you see blowout margins for Democratic Rep. Krysten Sinema in Arizona or Democratic Rep. Jacky Rosen in Nevada) you might see Democrats trying a different path to the White House, one that lets Trump have the Obama-to-Trump voters of the Upper Midwest, but tries to jump to 270 by winning Florida plus a more traditionally red but highly urbanized state like Georgia or Arizona.

I don’t know if that strategy would work. But if O’Rourke and Sinema do well enough, it might push Democrats towards that new strategy and pull our politics towards a different, stranger place that it’s been before.