Thérèse Dreaming, by the Polish-French painter Balthus, is undeniably creepy. Creepy enough to launch, in this day and age, an online petition demanding it either be removed from New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, or that “context” be added to the display. The museum abstained from any action, but it remains a cautionary tale.

As communications director Kenneth Weine said in a statement: “Our mission is to present significant works of art across all times and cultures in order to connect people to creativity, knowledge, and ideas.” Bending to the winds of our popular sex panic would undermine the existence of an institution like the Met, so they stood their ground.

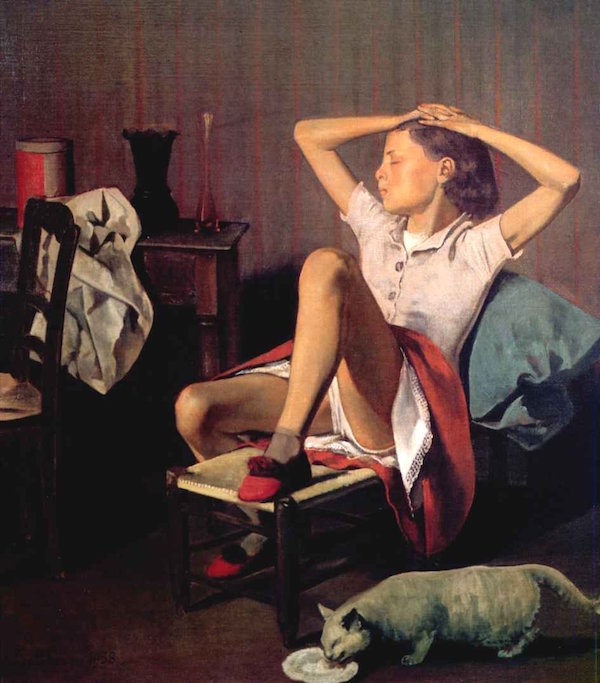

The petition by 30-year-old Mia Merrill requesting its removal may have misunderstood the museum’s reason for being, but she didn’t entirely misunderstand Balthus. She’d never seen Thérèse Dreaming before she and her sister came upon it, an unnerving depiction of young girl in awkward childish repose showing her panties, while a cat laps from a saucer of milk on the floor below. It hit them with that too familiar disgust and unfairness in which we find, more so since this October perhaps than ever before, fuel for a fighting cause.

“Given the current climate around sexual assault and allegations that become more public each day, in showcasing this work for the masses, The Met is romanticizing voyeurism and the objectification of children,” her petition reads. But disgust and unfairness, according to curator Sabine Rewald—who reclaimed Balthus as a subject for contemporary distaste—were always among this painter’s principal subjects. A Balthus, really, romanticizes nothing: In his work, as in the thrust of the #MeToo moment, the sexual impulse becomes a queasy and monstrous affront

Salty social media posts from art critic Jerry Saltz came down on the side of the sexploitatative artwork’s right to hang. “If you are talking about taking down or censoring work because it ‘offends,’ then you have to take almost everything out of the Met,” he told me, via email. From the pre-Columbian figurine to the contemporary pop ballad, no human output is safe from well-meaning erasure according to an historically unstable standard of decency.

A child un-self-consciously exposed—the subject of Thérèse Dreaming (from a favorite model of Balthus’s, a young neighbor)—forces on us the ugliness of knowing what she doesn’t: the erotic imposition of artist and viewer, plus the principled protest of the incensed activist determined to defend her, 90 years later.

Merrill’s petition, which garnered 11,529 online signatures, holds that swapping this Balthus for a painting by a woman or adding an updated label—to say presumably, and correctly, that leering at little girls is and always has been morally wrong—would advance women’s common cause.

It’s ironic she should respond thusly to Thérèse Dreaming, though, given that Balthus toyed with the troubling dimensions of an immoral and unconsented-to desire long before the politics of sexual consent ever ascended to the level of cultural currency they now hold.

His girls should unnerve us, and not only because Balthus intended them to. I see Thérèse’s poses and remember my grandmother instructing me always to cross my legs when I wore a skirt; I never asked why because, on another unspoken level, beyond my understanding, I already knew. Art’s purpose is, at some unspoken level, always to provoke within us that which cannot be confined by manners or contemporary expectations.

Revisiting curator Sabine Rewald’s Balthus revival, 2013’s Cats and Girls—Paintings and Provocations, Merrill’s protest was hardly the first reaction of its kind. A Balthus painting, Rewald offered in an interview at the time, “becomes about what the viewer brings to it. These children are flaunting themselves seemingly unobserved, but they are observed by the viewer. It is this unselfconscious, natural eroticism that he explores and makes into art.” Her argument, that these disturbing paintings reflect the onlookers’ own anxieties, fits our times exactly.

Saltz said something similar in our email exchange, which wandered from Roy Moore’s loss the night before to my presumed complicity in Donald Trump’s presidency (he asked at one point, whether I’d ended up voting for Trump, and signed off, “J’Accuse!”). However demanding the puritanical-progressive reflex may be, a viewer’s response to an artwork is always her own: “Art is subjective; each person brings different things to it,” he wrote, vindicating Merrill’s anger but not her cause. “Great art,” as Saltz also said, “is different for every person who sees it; in fact, it is so great that it is different every time *you* see it.”

The call to replace or recontextualize an offending painting neuters the painting’s power to hit every viewer differently—depending on the news of the day or her memory of a gentle scold from her grandmother one Sunday several years ago.

Or, as Balthus’s biographer writes, “I think he should be defended in particular because he attracts condemnation almost more than any artist of the last century.”

Nicholas Fox Weber, who runs the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, sent me a richly thoughtful addendum to his earlier published remarks—adding a layer to the feminist imperative that we “talk about Balthus.” Were Weber present for such a talk, we’d actually be talking about Balthus—not treating his repeat subject as a proxy in our evolving sexual politics.

Weber leads with the inevitable slippery slope, “Censorship is out of the question. Do we begin to take erotic Picassos off the walls of museums, and the Rokeby Venus, and then David Hockney’s naked pool boys?” But continues as only a biographer can, “For that matter, as Giacometti pointed out, Balthus could paint an apple and a lemon in a bowl on a window sill and they become erotic, so not only Thérèse would be deemed scandalous.”

Balthus, Weber tells me, bore a distinct resemblance to his mother, who was the lover of modernist poet Rainer Maria Rilke. And he prided himself as a young man on his peculiar seductive power over the man, drawing confidence from an interplay one must assume he did not entirely understand.

And Balthus’s girls, Weber believes, are so disturbing, so psychologically and sexually complex, precisely because of this formative, self-conscious sway he had over Rilke. He chose Thérèse as a subject because he recognized something of his young self in her. And, in his career as a painter of young girls, he grew inseparable from the subject he was famous for. As gender-bending “narcissistic self-portraits,” their profound effect on us is no accident.

And should the “current climate”—to borrow a phrase—that informed Merrill’s protest ever fully enfold the tensions Balthus toyed with into its overdue reconditioning of sexual morality, we’d learn a little more about the outer edges of our nature. More, anyway, than we get from affixing a new label next to the painting, or removing it altogether.