If Republicans take back the Senate in November, President Obama could order a staff shake-up — the go-to strategy for many of his predecessors at the lowest points in their presidencies.

But that type of move doesn’t always work — and has even worsened the headache for presidents who appear desperate to try anything to get the public back on their side.

Every president dating back to Lyndon Johnson has brought in fresh blood following a rough political patch. Some moves are more cosmetic, and others are meant to showcase a dramatic overhaul in how the White House conducts business.

Obama has seen the exit of nearly all of his original Cabinet members. However, changes to his inner circle at the White House have been mostly routine and hardly representative of a drastic rethinking of his agenda or how to best communicate his message to the public.

Late last year, Obama brought on John Podesta, Bill Clinton’s former chief of staff, to help prepare a slate of new executive actions and get the White House back on proper footing following the botched rollout of Obamacare.

Still, that move did little to change perceptions of the White House during a year in which Obama’s approval ratings hover around 40 percent and his agenda remains overshadowed by a barrage of crises at home and abroad.

If Obama tries to jump-start his final two years in office through a staff shake-up, he may want to study why some similar moves were dismissed as a political stunt rather than an upgrade in talent.

In certain cases, the timing of the White House pink slips negated the move altogether or simply hardened negative opinions of the president. Yet other shake-ups were considered defining moments that altered the trajectories of administrations in turmoil.

Here are the best and the worst staff shake-ups by presidents over the past 50 years.

BEST

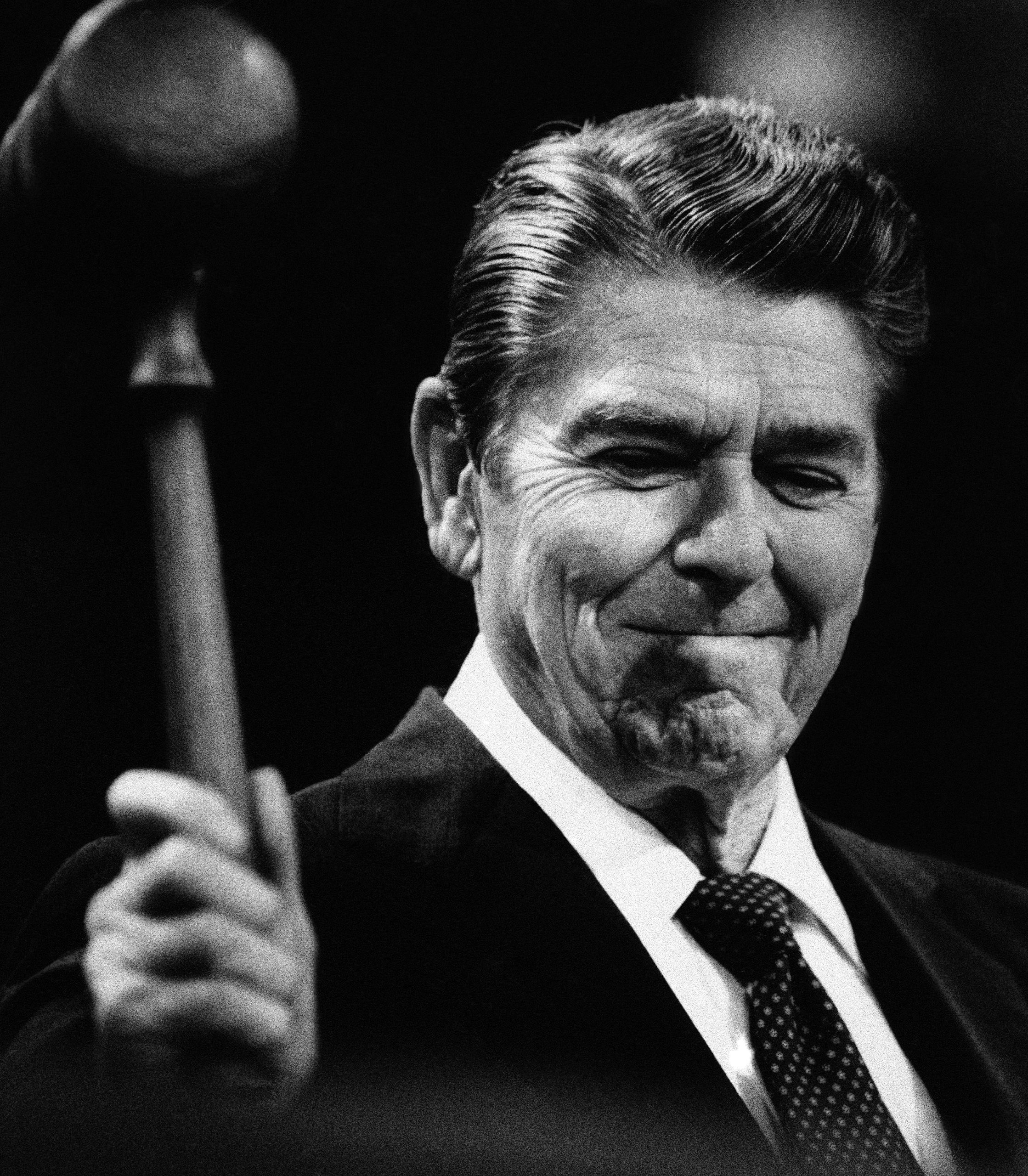

Ronald Reagan

At the height of the Iran-Contra scandal, Reagan fired his chief of staff, Donald Regan, who had been in the post for two years.

For Reagan, it was a calculated risk to let go of his former Treasury secretary, one of the leading proponents of “Reaganomics.” But the move paid off.

Regan’s replacement, Howard Baker, was cheered by Republicans and Democrats alike, who say the former Senate majority leader ran a more transparent White House, opened up the decision-making process to a deeper roster of advisers and improved the president’s relationship with Congress. The former California governor regained the trust of much of the public, thanks in large part to Baker, presidential historians argue.

Ultimately, Reagan left office with an approval rating above 60 percent, turning the dark days of Iran-Contra into a distant memory.

Bill Clinton

Leon Panetta is certainly a thorn in the side of the Obama White House these days, but he also was the central figure in one of the most effective shake-ups in modern presidential history.

In 1994, a brutal midterm election year for Clinton, the former Arkansas governor moved Panetta from the top post at the Office of Management and Budget to the position of chief of staff.

The Clinton White House, full of ideas but short on discipline, had squandered many of the biggest opportunities in Clinton’s first two years in office. Out went Clinton’s lifelong friend, Mack McLarty, and in came Panetta — and his no-nonsense managerial style.

“The president kind of said to me, ‘Look, you’ve got to just clean house with some of these people,’ ” Panetta said of his task. “I said, ‘Whoa. I’m just walking in. Let me get a few months to see what they’re like and what they can do.’ And, frankly, I found that a lot of them were actually pretty good people with a lot of experience and a lot of commitment. But what they didn’t have was the structure to work within. They just did not know what the process was like.”

Panetta forced Clinton to stay on message on the economy, not letting the president’s agenda get sidetracked by issues of less concern to Americans. In turn, Clinton saw his approval ratings rise, and his economic policies were given credit for sustained job growth.

Panetta also had the good fortune of getting out before the Monica Lewinsky scandal engulfed the remainder of the Clinton presidency.

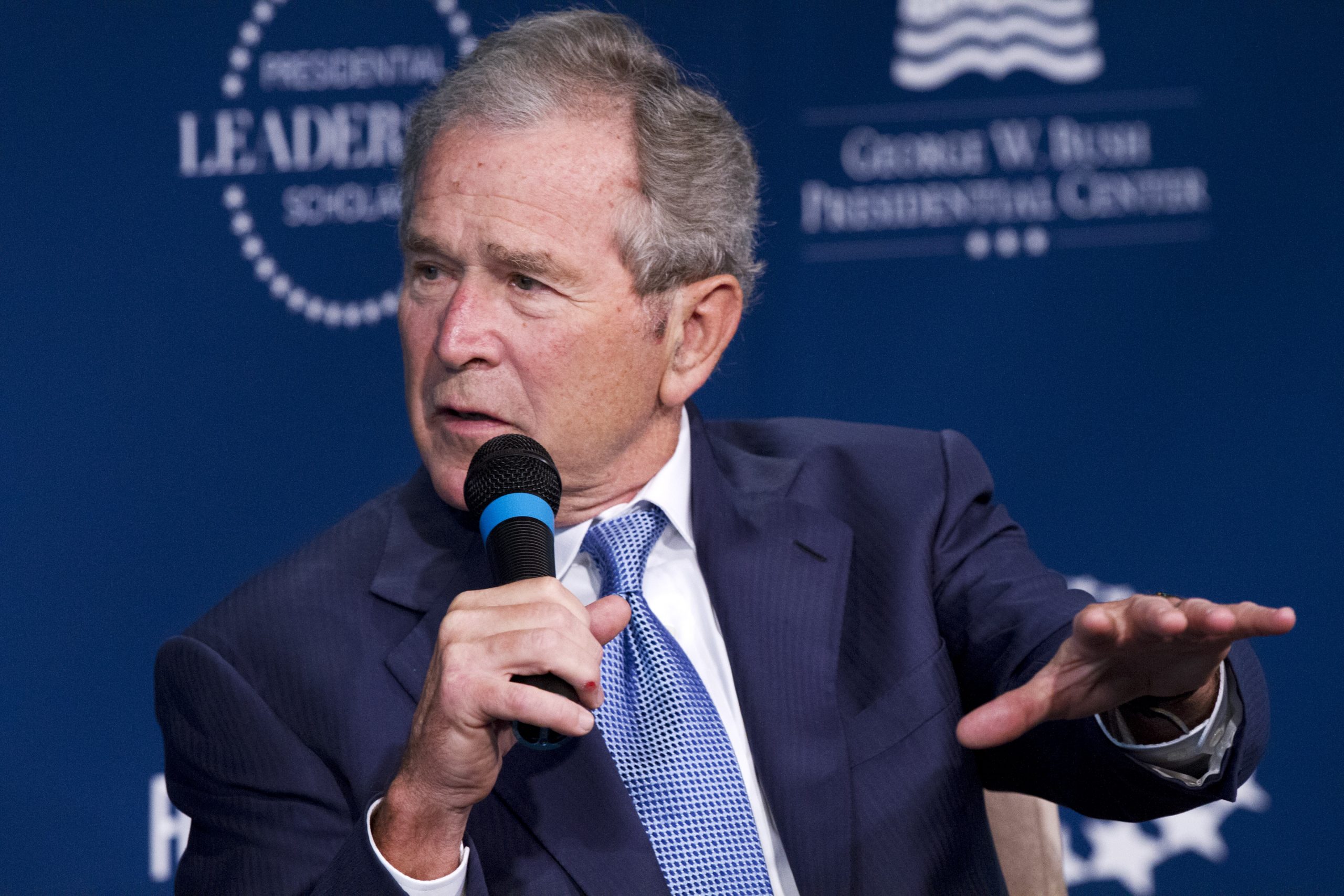

George W. Bush

Bush’s 2006 in many ways parallels Obama’s 2014: a lame-duck president facing the prospect of an opposition Congress at a time when the White House lacks political currency.

Then-White House Chief of Staff Andrew Card resigned in March and was replaced by Josh Bolten, which began a major housecleaning.

Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld resigned a day after the November midterms, giving way to Robert Gates at the Pentagon. Bush also brought in Henry Paulson as Treasury secretary and Michael Hayden as director of the Central Intelligence Agency.

Gates engineered major gains in Iraq and Afghanistan with troop surges that gave Bush positive developments in massively unpopular wars.

Granted, Bush never approached the level of popularity he enjoyed after his response to the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, but his revamped national security team helped to stop the bleeding.

WORST

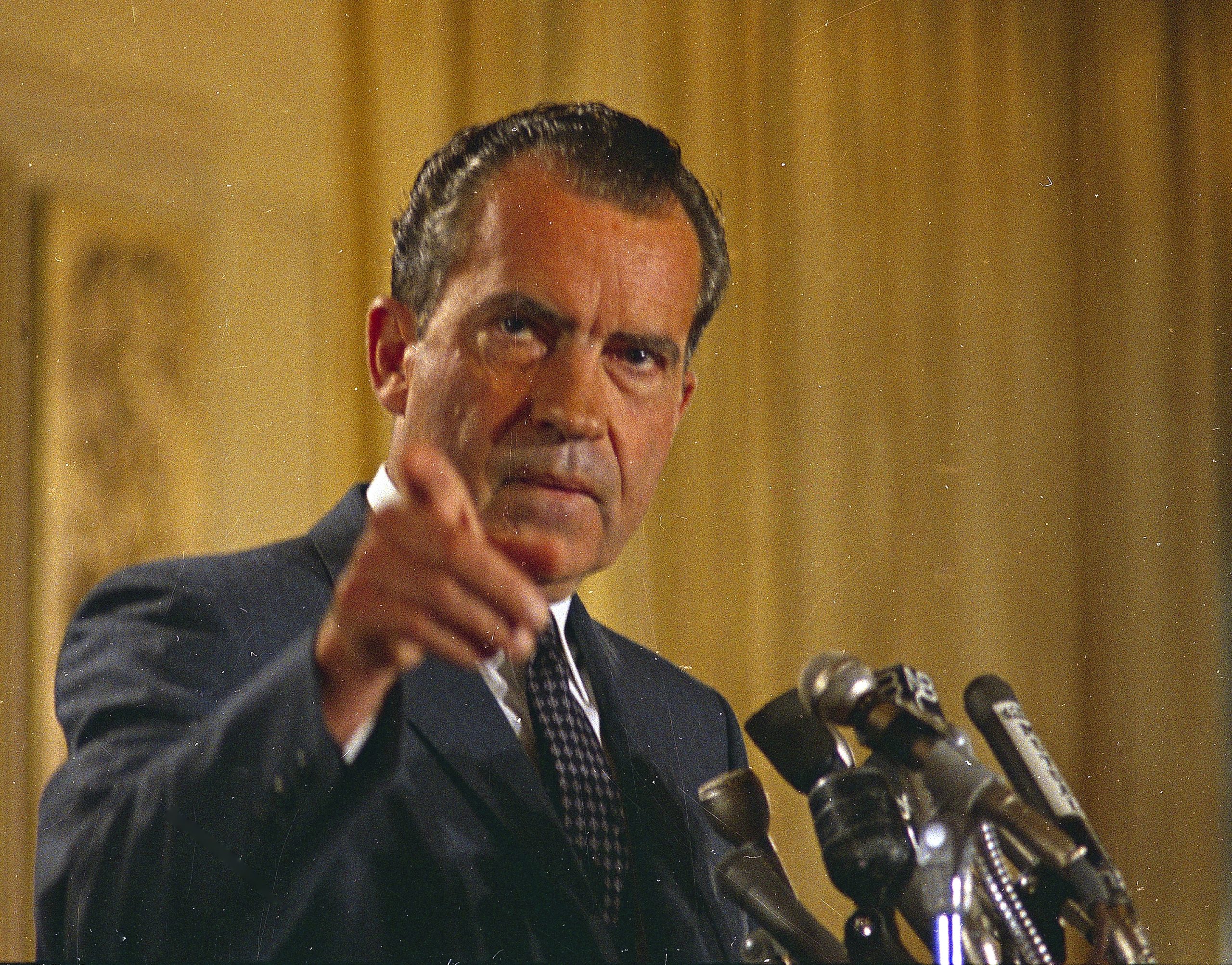

Richard Nixon

Nixon looked for plenty of scapegoats in the wake of the Watergate scandal.

In 1973, Nixon promised “no whitewash” of the investigation into the White House’s role in the burglary of the historic Washington hotel, accepting the resignation of chief White House advisers H.R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman. Attorney General Richard Kleindienst was replaced by Defense Secretary Elliot Richardson. Nixon also fired his counsel, John Dean, who was originally tasked with investigating Watergate.

It didn’t work.

Nixon was forced to resign, representing the lowest moment for any American president since the Civil War.

Jimmy Carter

Call it the post-malaise housecleaning.

After giving the most disastrous speech of his presidency in July 1979 — the “crisis of confidence” address in which he took Americans to task for “self-indulgence and consumption” — Carter requested the resignations of his entire Cabinet and senior staff, threatening to keep only a handful of his most trusted advisers at the White House.

Angered by the demand, many top administration officials, including five Cabinet members, called the president’s bluff and simply left the White House. Rather than bringing new energy to his team, most of the public believed Carter was giving up in the waning days of his first term.

Carter never shook off that perception and was clobbered by Reagan in the 1980 election.

Lyndon Johnson

Hoping for a game-changing moment in the later stage of his presidency, Johnson essentially pushed Defense Secretary Robert McNamara to the World Bank in an attempt to appease a public increasingly frustrated by the Vietnam War.

The appointment of Clark Clifford to the post didn’t much matter. Johnson was permanently tied to Vietnam, and his decision was dismissed as too late to alter the trajectory of a seemingly endless foreign entanglement.

A few months later, Johnson chose not to pursue re-election.