Donald Trump is historically unpopular. At the end of 2017, the three major polling aggregators—the HuffPost Pollster, Real Clear Politics, and FiveThirtyEight—put his approval rating at 40.4, 40, and 37.9 percent, respectively. According to FiveThirtyEight’s historical averages, this is the worst rating that any president has had at a comparable point since Gallup started asking the question in the late 1930s.

Trump had difficulties his entire first year. On almost every day since his inauguration, the president has had a lower approval rating than his predecessors. The notable exceptions are Gerald Ford and Bill Clinton. Ford’s numbers roughly matched Trump’s for a significant stretch of his first year and Clinton’s numbers briefly dipped below Trump levels in 1993. But those exceptions shouldn’t be comforting to the president. Ford wasn’t a picture of popularity—his numbers cratered after he pardoned Nixon—and Clinton’s overreach in his early policy initiatives is part of what led to the Republican wave of 1994.

It is pretty clear that voters didn’t like Trump in 2017.

Part of the problem was policy; most of the president’s major legislative pushes have been unpopular.

Republicans attempted to repeal and replace Obamacare multiple times last year, and they faced considerable pushback from the public. The American Health Care Act, which passed the House of Representatives in May, had the support of just 28.2 percent of respondents in an average of polls taken from March through May. (Polls were compiled by Chris Warshaw, a professor at George Washington University.) According to Warshaw’s averages, the House bill was less popular than Obama’s original 2009 Affordable Care Act and polled worse than Bill Clinton’s health-care plan, which ultimately failed in 1993. The Senate’s Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017 also polled poorly—a June NPR poll found that only 17 percent of adults approved of it. And in September, a CBS poll showed that most Americans disapproved of Graham-Cassidy (another proposed Obamacare replacement), with only 20 percent approving.

In December, Trump signed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, a major reform bill, into law. But it hasn’t polled well either. A December NBC survey showed that only 24 percent of Americans believed the tax plan was a good idea, and 41 percent believed it was a bad one. An average of November polls showed that only 32 percent of the public approved of the plan. It’s possible that these tax cuts could become more popular over time (a mid-January New York Times poll showed a bump in public support for the law), but the early trends were against it.

Put simply, the president’s main public-policy initiatives haven’t been very popular—which helps explain why Trump’s overall approval rating is as low as it is.

Another part of the problem is Trump himself. In a January 2018 Quinnipiac poll, 34 percent of respondents said the president was honest, 39 percent said he had good leadership skills, 38 percent said he cares about average Americans, 28 percent said he was level-headed, and 32 percent said he shares their values. Large segments of the American public think the chief executive has issues with competence and empathy.

Not all the numbers are bad for Trump. His approval rating on the economy consistently outpaces his overall approval rating, and in the same Quinnipiac survey, 66 percent of Americans said the economy was in good or excellent shape. And Trump scores better on strength (59 percent said he’s a strong person) and intelligence (53 percent say he’s intelligent) than on other characteristics.

In other words, voters are happy with the economy and see Trump as smart and strong, but they don’t see him as compassionate or a good leader and strongly dislike some of his policies. All this adds up to a low approval rating—and that’s a big problem for the Republican party.

The Price of Presidential Unpopularity

Historically, when voters are unhappy with a president, they take it out on his party during the midterm elections.

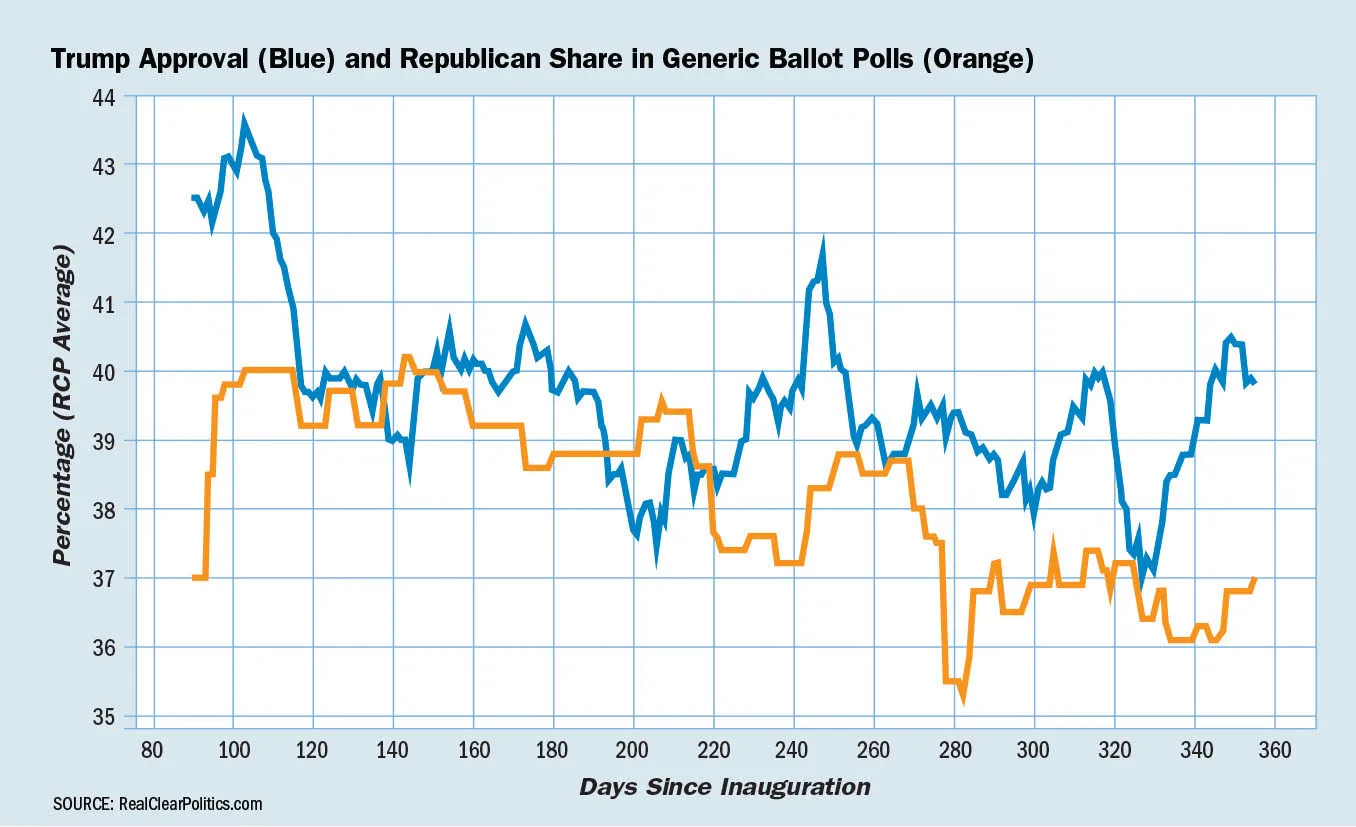

The graphic below shows how closely congressional Republicans are linked to Trump. His average approval rating, according to Real Clear Politics, is shown in blue, and the Republican party’s percentage of the vote in House generic ballot polls (polls that ask which party voters are going to cast their ballot for in the midterm House elections) is shown in orange.

Trump’s approval rating and the Republican share of the generic congressional vote typically aren’t far off each other. This suggests that voters who disapprove of Trump are unwilling or at least hesitant to support the congressional GOP.

And the problem for Republicans isn’t just in polls; they had trouble in elections throughout 2017.

Since Trump took office, Republicans have had uncomfortably close calls in a number of special elections. In South Carolina’s 5th congressional district (which Trump carried by 18.5 points in 2016), Republican Ralph Norman beat the Democratic candidate by 3 points. In Montana’s at-large congressional district (a state Trump won by 20 points), Republican Greg Gianforte won by 6 points. GOP candidate Ron Estes won the special election in Kansas’s 4th district by single digits. Trump won this district by 27 points in 2016.

It’s possible to explain away individual races. Norman’s Democratic opponent, Archie Parnell, was a strong candidate. Gianforte made headlines by assaulting a reporter for the Guardian. Estes may have been hurt by his association with unpopular Kansas governor Sam Brownback. But it’s hard to explain away the sum of the evidence. In special elections since Trump won the presidency, Democrats have outperformed their 2016 margin by 11 points on average.

In both the Alabama special Senate election and Virginia’s gubernatorial race, Democrats made gains in well-to-do suburban areas. In 2016, Trump won critically important states in part by trading college-educated voters for non-college-educated white voters. The results in Alabama and Virginia suggest that some of these traditionally Republican voters are angry enough with Trump to turn out strongly for Democrats. Turnout, though, was down in rural areas with numerous non-college-educated white voters in 2017—the voters Trump had compensated with in the presidential election. Even in the smaller contests (e.g., Kansas’s 4th District, Montana’s at-large special election), the leftward shift in the overall results suggests that Republicans have a problem with both turnout and voter share.

Every election result has more than one cause, but Trump is the source of many of the problems. The voters that Trump alienated in 2016 turned out heavily to register their dissatisfaction with him in 2017. And it’s not a stretch to think that some Republicans who don’t like Trump or don’t feel inspired to vote for him will stay home or cast their ballots for a Democrat.

Will the Midterms Look Any Different?

The sum of the evidence suggests that Democrats will have a significant advantage in the 2018 midterms.

GOP candidates have been underperforming Trump’s 2016 margins in House special elections, and Republicans in key districts have been retiring. Ed Royce of California’s 39th District, Ileana Ros-Lehtinen of Florida’s 27th District, and Dave Reichert of Washington’s 8th District all managed to win reelection in 2016 despite Clinton beating Trump in their districts. All are retiring in 2018. There have been some key Democratic retirements as well (e.g., Tim Walz of Minnesota’s 1st District is running for governor instead of reelection). But overall the data suggest that the Democratic base is energized, the Republican base (which is now less dependent on college-educated whites) might not turn out, and some independent or traditionally Republican voters may be willing to vote for a Democrat to register their frustration with Trump.

That’s not to say that Republicans have no chance of holding the House. The map strongly favors the GOP (numerous Democratic voters are packed into a few congressional districts, while Republican are more efficiently spread out), and Republicans could theoretically lose the House popular vote by several points without losing control of the chamber.

But Democrats do have significantly better than 50-50 odds of taking the House in November. In 2010, House Republicans had a 9.4 point lead heading into Election Day; they won the popular vote by 7 points and netted 63 seats, becoming the majority. In 2006, Democrats won the House popular vote by 8 points (slightly underperforming their 11.5 point lead), took 31 seats, and gained control. And while Democrats led in polls at this point in the 1994 cycle, Republicans retook the House by winning the popular vote by 7.1 points and netting 54 seats. Democrats currently hold a 10.5 percentage point lead in the generic House ballot, and these polls typically move away from the president’s party as the midterms approach. It’s hard to know exactly what margin Democrats need to retake the House, and political patterns aren’t laws of nature—conditions can improve for Republicans before November. But it’s hard to look at the present Democratic advantage and conclude that Democrats have a less than even chance of retaking the lower chamber.

It’s tougher to tell who will win the Senate. Democrats have the wind at their back, but Republicans have an extremely good map. To take back the Senate, Democrats basically have to pitch a perfect game. They need to defend multiple seats in very red states—West Virginia, North Dakota, Montana, Indiana, and Missouri.

There are some signs that West Virginia’s Joe Manchin, North Dakota’s Heidi Heitkamp, and Montana’s Jon Tester are safe—they all registered greater than 50 percent approval in deeply red states in late October, according to Morning Consult. They have also shown themselves to be formidable campaigners in the past. Indiana’s Joe Donnelly doesn’t fare as well as Manchin, Heitkamp, or Tester in approval polls, but in his 2012 race, he showed some signs of political skill. He managed to keep a difficult race close until his opponent, Richard Mourdock, made controversial comments about abortion (specifically that pregnancy due to rape was something “God intended”), and he outpaced Obama in parts of the state that would vote heavily for Trump in the 2016 Republican primary.

Missouri’s Claire McCaskill is the weakest Democratic incumbent. Her favorability numbers don’t suggest that she’s built a strong personal brand like Manchin or Heitkamp. McCaskill’s two Senate campaigns haven’t, moreover, been very impressive. Last November, I used regression analysis to examine whether she performed better or worse than a generic candidate after controlling for incumbency, the state’s partisan leanings, and the fact that she faced a problematic candidate (Todd Akin and his famous remarks about “legitimate rape”) in 2012. There is little evidence that she did better than a generic Democrat would have.

Even if Democrats manage to hold all those seats, they still need to take two to gain a majority. The likeliest targets are Arizona and Nevada, and Republicans face different difficulties in these states. Nevada senator Dean Heller is walking a tightrope. He has to stay close enough to Trump’s wing of the party to fend off primary challenger Danny Tarkanian (who has yet to show any ability to win a general election, having lost races for the U.S. Senate, the U.S. House of Representatives (twice), the Nevada state senate, and Nevada secretary of state), yet maintain enough distance from the president to build his own brand in a state that voted for Hillary Clinton.

In Arizona, Republicans are engaged in a divisive primary with Kelli Ward (an alt-right favorite who ran hard against John McCain in 2016) and Joe Arpaio (recently pardoned by President Trump for criminal contempt of court related to a racial-profiling case when he was sheriff of Maricopa County) vying for the support of the Trump wing of the party, and Representative Martha McSally attempting to win the more establishment-friendly vote. Whoever makes it out of the primary will likely face a tough race against Democratic representative Kyrsten Sinema, but a Ward or Arpaio nomination would make the race much more difficult for the GOP to win.

There’s not a lot of polling in either of these races yet, but they’re both winnable for Democrats—Larry J. Sabato’s Crystal Ball rates the races as toss-ups.

The Gubernatorial Map

There are 36 gubernatorial races in 2018, from deep-red Texas to bright-blue Hawaii. It’s harder to gauge what’ll happen in these races. Governors don’t work on national issues in the same way that congressmen do, and voters take that into account. How a state votes in a presidential election strongly influences which party is favored in Senate contests, but presidential-level partisanship has significantly less predictive power in gubernatorial elections. That’s part of the reason Vermont, Maryland, and Massachusetts have Republican governors, and Montana and Louisiana have Democratic ones.

That being said, we should expect some Democratic gains. The president’s party has lost governorships in almost 80 percent of the midterm elections since World War II. Republican incumbents, moreover, are term-limited in key states like Maine, New Mexico, Ohio, Michigan, Nevada, and Florida.

But blue gains might not all be in the usual places. In 2014, for example, Republican Charlie Baker won the governorship of Massachusetts by running a socially liberal, fiscally conservative campaign, and Larry Hogan won a surprising upset in Maryland. Yet Republican governor Tom Corbett was unable to hold his seat in a race against Democratic businessman Tom Wolf in Pennsylvania, a quadrennial swing state. Given the 2018 map, it’s not hard to imagine Democrats making gains in heavily Hispanic New Mexico or light-blue Nevada but losing deeply Democratic Connecticut, where sitting governor Dannel Malloy is highly unpopular.

It’s worth watching gubernatorial elections on a race-by-race basis. Democrats will likely make gains, but there are competitive races outside the typical swing states. And incumbent Democrats who win reelection in 2018 are likely to try to run for president (e.g., Pennsylvania’s Wolf and Andrew Cuomo of New York).

So in the end what we know is that voters are unhappy with President Trump—both personally and on policy. Democrats are highly motivated to register their opposition to the president, and Republicans had turnout issues in 2017. Conditions can change, but as of now Democrats look like they’re going to make significant gains in the midterm elections and chart a path to 2020.