The Obama administration’s strategy to fight the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria depends heavily on the success of local forces, Pentagon leaders told skeptical lawmakers Wednesday, drawing questions on whether that’s enough to protect U.S. interests from a dangerous threat.

“If you’re asking, ‘Is the United States winning?’ that’s the wrong question,” Joint Chiefs Chairman Gen. Martin Dempsey told the House Armed Services Committee.

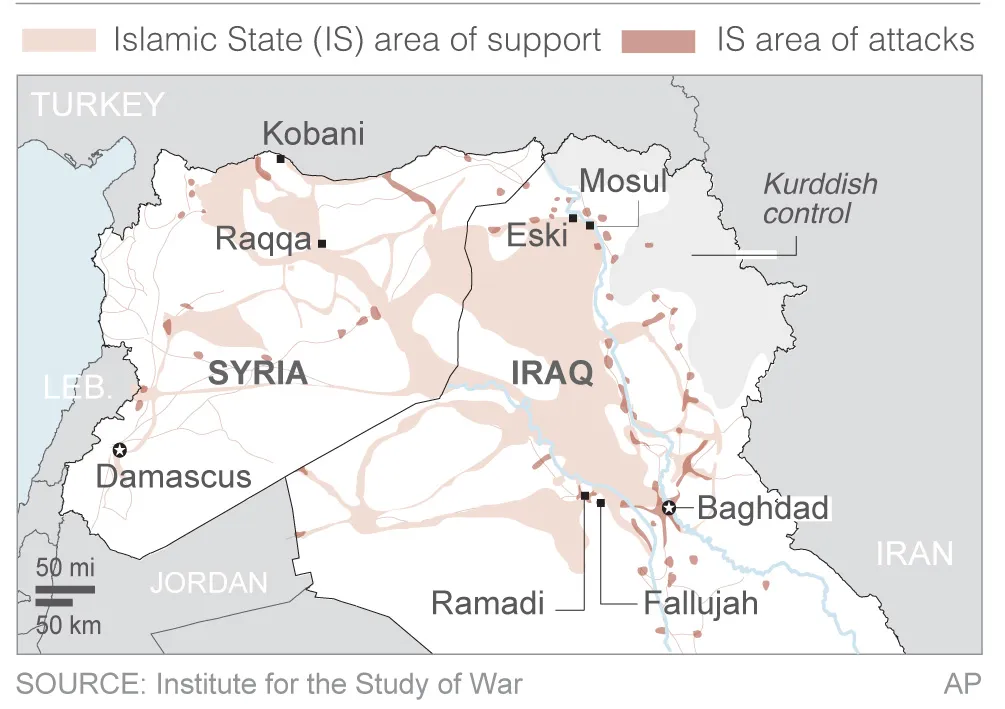

He and Defense Secretary Ashton Carter were summoned before the committee to discuss U.S. strategy in the Middle East amid concerns that the Islamist extremist group maintains the upper hand in spite of a year-long U.S.-led effort to defeat it. Those concerns have stalled efforts to get Congress to give formal authorization to the military campaign and led to calls for a renewed direct U.S. role in ground combat in the region.

Though the U.S.-led coalition bombing campaign has hurt the Islamic State in significant ways, it has not led to a strategic reversal of the group’s position, particularly as it expands into new territories, such as Libya.

But Obama has strongly resisted what many experts and lawmakers say is necessary and some Iraqis openly want the United States to do: send ground combat troops back to Iraq. Instead, the administration has offered a ramped-up training program for Iraqi troops bolstered by the addition of 450 U.S. advisers to the more than 3,000 already in the country, combined with pressuring Baghdad to do more on its own — a number many lawmakers have criticized as a pittance.

The administration also is planning direct supplies of weapons and training to Sunni Arab tribes and Kurdish peshmerga forces, two groups that still view the Shiite-dominated government in Baghdad with suspicion, but will do that in cooperation with that government.

“With respect to Iraq, the critical ingredient of a strategy is strengthening local forces,” Carter told the panel, noting that the additional 450 U.S. troops were dispatched to set up a training facility at Taqaddum, in the heart of Sunni Arab territory, to help recruit and train more of them into the fight, both as regular Iraqi troops and tribal forces.

Though Congress has budgeted for training 24,000 new Iraqi troops, only 7,000 recruits have shown up, Carter said, mainly because of Sunni Arab reluctance to join the fight.

“The whole point of Taqaddum is to close that gap,” he said. “It’s not the number of people there, it’s the leverage they’re going to have.”

Some Democrats openly wondered if that would be enough of an adjustment to reverse recent gains by the Islamic State, and whether the administration’s commitment to Iraq’s unity under the government in Baghdad is hurting efforts to defeat the group. The House voted last month to allow the administration to send arms directly to Kurdish peshmerga forces and Sunni Arab tribes, bypassing the government.

“Are we actually trying to hold together in Iraq that which doesn’t want to be held together?” asked Rep. Jim Langevin, D-R.I.

Rep. Tulsi Gabbard, D-Hawaii, one of several veterans of the 2003-2011 Iraq war on the panel, suggested that the administration should reconsider its support for the government of Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi because the continuing threat of Shiite sectarianism is “further adding fuel to the fire of sectarianism.”

Republicans want to go further, and have pushed the administration to back off its unwillingness to commit U.S. ground combat forces to the fight, influenced in part by suggestions from experts and political leaders in the region that those forces would bolster reluctant allies and add capacities they lack.

“I would not recommend that we put U.S. forces in harm’s way simply to ‘stiffen the spine’ of local forces,” Dempsey said. But he and Carter noted that they were open to bringing U.S. troops forward into limited combat roles if that can help enhance the success of Iraqi forces once they are ready to take the offensive.