Let’s call her Jane. She’s 32 and a junior vice president at a big investment bank. The firm’s attempt at more manageable hours has made it possible for her to reshuffle her work and stay on after having a baby. But growing responsibilities to clients pull her away from her new role. She totes little Jack to the office on Saturdays and balances her travel schedule so that either she or her husband can be home each evening. When Jack is 2 going on 3, he diverts this promising high-powered career with a single game of “pretend.” As she remembers it, he said, “ ‘Pretend you’re a kid, and I’m your mommy.’ I agreed, and so he said, ‘I’m the mommy, I’m going to work. You’re the kid, you cry.’ ” Needless to say, Jane did.

Now consider Luis, 39, a single dad with a full-time job as a line cook at a restaurant on Capitol Hill. The age gap between young parents and the unencumbered at this workplace is about the same as among the bankers. Almost all the employees in their 30s are kitchen staff with kids at home, while the wait staff is made up of 20-somethings still living with roommates. When a sick babysitter means missing a shift, Luis has to negotiate a last-minute cover with the rest of the staff. “If it happens too often, we’d have to find a full-time replacement for the good of the restaurant,” the assistant manager tells me. “Fortunately, we’re like a family,” and someone’s almost always ready to step up. But the assistant manager is still young, in her mid-20s, and if she were pregnant there would be no possibility of paid maternity leave. In this sort of business, if you don’t work, you don’t get paid.

President Donald Trump’s 2018 budget proposal earmarked $19 billion over the next 10 years for paid leave for new parents whose employers provide none: six weeks covered by an unspecified reform of state-level unemployment benefits and increased payroll taxes.

The introduction of a new unfunded federal mandate raises many questions, most with no ready answer. But two things are clear. One, a healthy balance between family and professional duties eludes workers at all strata of American life. It’s a universal, though variously manifested, challenge most large companies, six states, dozens of cities, and every other developed nation have taken on. Second, the very presence of paid leave in the president’s “America First” budget constituted a win for Ivanka Trump, who was the driving force behind her father’s campaign promise of paid leave for new mothers.

When Ivanka Trump introduced the next president of the United States at the Republican National Convention last July, she conjured a portrait of him—my father the feminist—foreign even to his most loyal supporters. And she stumped on atypical topics for the biggest gathering of Republicans: the wage gap and paid family leave. “Women represent 46 percent of the total U.S. labor force,” she barnstormed with perfect poise. “And 40 percent of American households have female primary breadwinners.”

Trump’s campaign promise was actually less progressive than what his budget proposed in May. The new plan would extend to fathers, like Luis, and adoptive parents—though the particulars of the coverage would be left up to each state’s discretion.

Getting a price tag in the proposed budget doesn’t mean a policy will count among congressional priorities. But putting paid family leave into wider consideration counts for something in Washington, and the paid-leave initiative got a standing ovation during the president’s joint address to Congress in February. The first daughter has pushed a debate long-running among the city-dwelling center-left power elite onto Capitol Hill. It concerns the still-fractious concept of the “motherhood gap,” at the edge of which women like Jane too often exit the fast track of the white-collar world.

THE MOTHERHOOD GAP

Ivanka Trump’s counterpart at the Democratic convention was Kirsten Gillibrand. “Families today look almost nothing like they did a generation ago,” the junior senator from New York announced. “Eight in 10 moms work outside the home; 4 in 10 moms are the primary or sole breadwinners, and many are single. . . . Yet today our policies are still stuck in the Mad Men era.” The Senate’s premier working mom, she noted that “child care can cost as much as college tuition” and that Washington is far behind the new reality in America.

The data don’t lie. Both husband and wife work in 61 percent of families in which the parents are married, according to the latest numbers from the Department of Labor. Seventy percent of mothers with children under 18 were working or looking for work in 2016. Mothers’ workforce participation shrinks the younger their children are: About 65 percent of mothers with children under 6 worked in 2016, but only 59 percent of mothers of infants. Tellingly, married mothers with small babies are far less likely to be looking for work than those single or divorced—3 percent versus 12.

Stories like Jane’s help explain the gender disparity in the middle and upper rungs of top financial firms and the quickening flurry of attention every time a new study quantifies the underrepresentation of women in American corporations’ C-suites—one expression of the motherhood gap, a more accurate name for that symptom of systemic sexism often called the “wage gap.” Economists Marianne Bertrand, Claudia Goldin, and Lawrence Katz concluded, after tracking close to 3,000 University of Chicago M.B.A.’s who graduated between 1990 and 2006, that women’s earnings fall behind men’s because of motherhood and the choices it foists on working moms: “[T]he observed patterns of decreased labor supply and earnings substantially reflect women’s choices given family constraints and the inflexibility of work schedules in many corporate and finance sector jobs,” they wrote. A Harvard Business Review survey, which Sheryl Sandberg cited in her bestselling book Lean In, found that 43 percent of “highly qualified women” with children cease working at some point. (One can wonder if Facebook COO Sandberg, who earned her business degree at Harvard in the mid-1990s, was one of the women they surveyed.) The same survey found that just 24 percent of men similarly “off-ramp” from their careers—and most of these not because of the burdens of children.

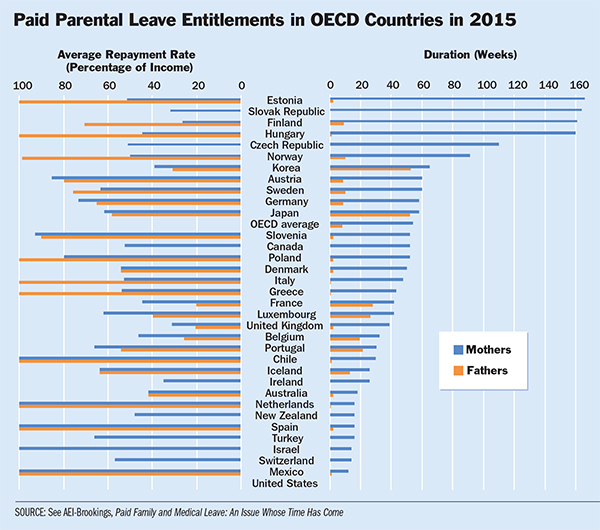

The United States stands alone among 41 economically comparable democratic nations in not mandating paid leave for new parents, according to data presented last year by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. The U.N. reported in 2014 that only Suriname, Oman, Papua New Guinea, and a smattering of South Pacific islands joined the United States in offering new mothers no form of paid leave. (Oman has since established a 50-day paid maternity leave.) Half a dozen predominantly liberal states—California first among them but also New Jersey, New York, Washington, Rhode Island, and the District of Columbia—and more than 30 cities (San Francisco’s fully paid leave policy, for instance, surpasses the state-level offerings) have enacted paid-leave mandates, but different ones, which multistate companies struggle to meet.

Under the conveniently vague catch-all of “pro-family policy” are a wide variety of proposals fighting for attention on Capitol Hill. There’s a confusion of goals and ideal beneficiaries that seem at cross-purposes in bills that claim a common cause—improving the work-life balance for American families. Any autopsy of paid-leave promises would diagnose a terminal diversity of definitions, whether it’s partly or fully paid, federally mandated or entirely optional but tax-incentivized and tiered. The leading Democratic proposal sets leave at 12 weeks, while IvankaCare asks only for 6. But even to consider these, in the interest of that elusive compromise, requires a common understanding of what “paid family leave” means—what should it accomplish and who is it for? The answers, of course, depend on whom you ask.

FIRST DAUGHTER, WORKING MOTHER

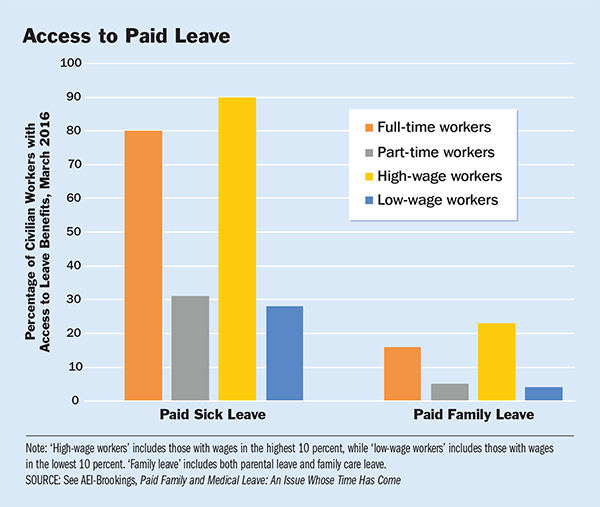

“Politicians talk about wage equality, but my father has made it a practice at his company throughout his entire career,” Ivanka Trump told the tens of millions watching the Republican convention. Under the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993, companies with 50 or more employees—like the Trump Organization—must offer 12 weeks of unpaid leave to workers with a new baby at home. But small businesses are exempt from the rule, and losing 12 weeks’ wages would be an unbridgeable hardship for most new parents working for an hourly wage. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, just 7 percent of private-sector workers in service fields had access to paid family leave last March. Overall, 13 percent of private-sector workers had access to some form of paid leave, while 28 percent of those working in management, business, or finance had such a benefit.

Ivanka, who became an executive vice president at the Trump Organization at age 24, wants to be seen as a working mother first. She illuminated the Trump campaign’s pro-family platform in an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal last September, calling for six weeks’ of paid maternity leave. “The current federal policies created to benefit families were written more than 65 years ago when dual-income families were not the norm,” she wrote. “Today, however, in about two-thirds of married couples, both spouses work,” she added. “Gender is no longer the factor creating the greatest wage discrepancy in this country, motherhood is.”

The transferability of a billionaire’s daughter’s situation is a difficult premise for any political argument. Ivanka knows she’s not the natural target for paid-leave proposals, says Angela Rachidi, who studies poverty at the American Enterprise Institute: “The people who are the ones being forced to go back to work when their babies are a week old, it’s not Ivanka Trump’s friends, and it wasn’t me and people like me. We figured out a way to make it work. It’s really the low-wage, low-skilled workers who don’t have a lot of options.” Rachidi was a member of a joint AEI-Brookings Institution working group that in June produced a plan calling for eight weeks of job-protected leave for all new parents—mothers, fathers, adoptive, biological. They would receive 70 percent of their pay, up to $600 per week, in a revenue-neutral proposal covered by an increased payroll tax on employees and equal cuts in federal spending. Ivanka previewed the plan before its publication and reportedly “loved it.”

Abby McCloskey was another member of the working group. An economist, political consultant, and leading conservative advocate for paid family leave, she was pregnant during the 2016 presidential primaries while working as a policy adviser for Texas’s Rick Perry—who dropped out of the race just at the tail end of her two-month paid maternity leave from the campaign. Republicans, she says, are “pro-life, pro-family, pro-opportunity,” and they face a values test with the issue of paid leave. “If they don’t move on this, I think it will be an obvious sign, and it’s not just that they didn’t like the Democrats’ proposal or it was impossible to come to a compromise,” says McCloskey, an expectant mother once again. “This is an issue that is central to what the party says it values.” Republicans, she adds, will have “no one else to blame if this doesn’t pass, so that’s a really heavy burden and a crucial test.”

As younger lawmakers inherit the GOP, the Eisenhower-era ideal of household roles fades further from memory and new types of pro-family policy are gaining ground. McCloskey perceives “more appetite for this policy among younger politicians, and certainly among women politicians who have experienced firsthand having a child and breastfeeding.” Marco Rubio, she notes, is a 46-year-old father of four. “I think the reason why he would propose a plan, and why Ivanka Trump in her mid-30s would make it her focus, is that people who have first-hand experience [of the modern family] are going to be the biggest advocates.”

“While the public policy process is messy and slow,” says McCloskey* a professor of social work at Columbia, “the ground is softening on paid leave.” In a poll by the National Partnership for Women and Families around the time of the election, 82 percent of voters agreed that Congress and the new president should explore paid family leave and 78 percent that they would like a “national paid family and medical leave fund” to foot the bill for 12 weeks off when life overtakes work. What exactly that legislative exploration would look like—and how it would be funded—will be for Congress to decide.

THE TAX CREDIT TWO-STEP

Early in her father’s presidency, Ivanka Trump summoned the Republican women of Congress to the White House to talk about paths ahead for child-care and paid-leave policies. But the likelier a proposal is to succeed on the Hill, the less it looks like Ivanka’s ideal of paid parental leave. In the weeks after her plan got that federal price tag—$19 billion over 10 years, from state-level reallocations—the Trump administration (in which Ivanka is a senior adviser to the president) considered a conservative alternative. On June 20, the first daughter and nine Republican congressmen sat around a table at the invitation of Marco Rubio and talked “pro-family tax policy.” The Florida senator had approvingly retweeted Ivanka’s praise of the AEI-Brookings report. “In America, no family should be forced to put off having children due to economic insecurity,” Rubio wrote on June 6. “@IvankaTrump is doing important work.”

Yet his fellow Republicans aren’t buying. Arizona senator Jeff Flake, a Trump critic, said that no proposal that levied a new payroll tax would be “seriously considered” by their conference. Roy Blunt of Missouri, who chairs the Senate subcommittee in charge of budgeting the departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, tells me that paid leave, while “a good idea” in theory, isn’t in Republicans’ plans. Programs to fund research into mental health and opioid abuse treatment “will continue to be priorities that will likely take precedence over a new unfunded issue like paid family leave,” he says. And the chair of the Senate Finance Committee, Orrin Hatch of Utah—who told reporters shortly after the budget’s release that he supports paid leave—equivocated in a prepared statement: “While this is a worthy goal, there are a variety of ways it can be achieved.”

The following week, Senate conservatives had a plan to push the White House their way—toward a preexisting tax credit proposal that targets families with children under 5 and does not require parents to prove they are employed. The subject line of a June 13 email from Rubio to Republican lawmakers invited them to a “Meeting with Ivanka Trump on Child Tax Credit,” signaling his and Utah senator Mike Lee’s intention to sell the first daughter on their modest substitute, one they’d included two years prior in a joint tax proposal that failed. The Lee-Rubio plan expands the existing child tax credit to give parents with children not yet in school $2,500 per child, per year—a $1,500 increase on the $1,000 credit already enshrined in the tax code.

In the June 20 meeting, Ivanka heard multiple policy proposals. “She was an active listener,” says Nebraska senator Deb Fischer, whose Strong Families Act—a tax credit to reward employers for offering up to 12 weeks of paid family leave—remains the only recent bill of its kind to be introduced by a Republican. Fischer’s mind is on working-class Americans, those without a safety net to fall back on. “I think we do have a consensus, Ivanka and I, that this is the group we need to target.” She has high hopes for the presidential embrace of paid leave, because as she says of her own legislation, “It’s been kind of tough to get it moved.”

Republicans have a long record of substituting tax credits for paternalistic social policies. In 1971, Richard Nixon vetoed a bipartisan child-care subsidy at adviser Patrick Buchanan’s urging. But five years later, Gerald Ford enacted an alternative that was less challenging to traditional mores: a dependent and child-care tax credit, which George H. W. Bush later expanded into a direct subsidy to help parents make ends meet.

“I think it’s great!” says Abby McCloskey, when I ask her about the Rubio-Lee tax credit seeming like a surer thing than paid leave as proposed. “It’s less targeted,” she adds, pointing out that while it lacks the economic benefits of paid leave, it gives parents flexibility. The child tax credit expansion is expected to lead a “pro-family” package in Republicans’ tax reform plan this fall. And even if tax reform falls through, we may well see a standalone child tax credit bill.

Angela Rachidi is more critical than McCloskey of conservative senators’ desire to substitute tax credits for paid leave. “There are reasons to expand the CTC,” she concedes, “but there are really no good arguments to make it a substitute for these other policies that are needed. It’s a mistake.” In her view, Rubio and Lee’s proposed raising of the credit to $2,500 per year means little to the low-wage worker who takes six weeks of leave at a loss of $2,100. “It runs a risk of being a new federal expenditure that’s not going to have very meaningful results,” she tells me.

WOMEN WHO WORK—ON CAPITOL HILL

Both Deb Fischer and Kirsten Gillibrand are pushing bills in the Senate that would give workers 12 weeks of paid leave. But there’s a deep difference, one that reflects their disparate backgrounds and ideas of America.

Fischer is a moderate Republican from a western state. She raised a family first, then pursued a public career—a degree at her state university followed by successful campaigns for local, state, and national offices. She and her husband are ranchers. The Fischer family followed a premodern model of home economics, and for as long as her three sons worked alongside their father, investment in their upbringing showed returns in their labor. Most people don’t do it that way anymore. So when Fischer sells her paid-leave bill—a 25 percent tax credit for employers who offer 12 weeks of paid leave to their workers—to colleagues and to the press, she doesn’t talk about herself. She talks about single parents waiting tables and adult children caring for infirm parents while working retail for an hourly wage to make ends meet.

Gillibrand is the junior senator from one of the most populous and powerful northeastern states. She has a banker husband, a moderately preppy pedigree—she’s a graduate of Emma Willard and Dartmouth—and a Democratic activist grandmother whose legacy propelled her toward political office after a high-powered law career. She was in her second term in the House of Representatives in 2009 when she was picked to replace Hillary Clinton, who’d become Barack Obama’s secretary of state. Gillibrand had only recently given birth to her second son. The spotlight and the timing of her pregnancy turned the first-ever breastfeeding senator from a conservative “blue dog” Democrat to a women’s rights activist.

Both of these lady lawmakers’ ideas for paid family leave cite flaws in the 1993 Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) as their legislative inspiration—unpaid leave won’t help low-wage workers. Passed two weeks into Bill Clinton’s presidency, the FMLA built on job-protected leave policies that had already been enacted in 34 states. It foreshadowed Clinton’s “Middle Class Bill of Rights,” which introduced a new child tax credit four years later. Unlike President Ford’s child tax credit, which can cover as much as 35 percent of care costs, the Clinton tax credit offered parents a set sum per child. In his first term, George W. Bush doubled the credit-per-child, from $500 to $1000. It is this credit that Rubio and Lee now seek to expand to $2,500. Fischer and Gillibrand welcome such an expansion, but only in addition to and not instead of passing a paid-leave bill.

Gillibrand’s Family and Medical Insurance Leave Act (known as the FAMILY Act) offers a uniform 12 weeks paid leave for illness (family or personal) or the birth or adoption of a child. It would be administered through Social Security and funded by tax hikes on both employers and employees. Only about 59 percent of working women are actually eligible for unpaid leave, and the eligibility is much lower for low-income women: Department of Labor surveys have found that unpaid-leave takers’ most common worry is financial loss. A mere 6 percent of employers required to provide leave under the existing law gave their workers fully paid leave as of 2016.

Gillibrand enthusiastically welcomed Ivanka Trump’s advocacy of paid leave and hoped for wider Republican support. Her bill’s great stumbling block since its introduction in 2013 has been its failure to catch a single conservative cosponsor. Although it boasts a lengthy roster of progressive supporters—from Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren to Chuck Schumer and Dianne Feinstein—the bill has never won the approval of centrist senators like Tim Kaine, Mark Warner, or Joe Manchin. All three put their names on Deb Fischer’s employer incentive plan.

When I ask Gillibrand whether she would consider a compromise on paid family leave with the White House’s blessing—and named the AEI-Brookings’ eight weeks for new parents as an example—she indulges the hypothetical only to swat it away. “It’s not what I support. It’s limited and not paid for.” A staffer chimes in, “It leaves out 75 percent of the people that our bill would cover.”

NEW PARENTS VERSUS OLD PARENTS

This figure reflects one of the complexities of paid-family leave discussions: People are often talking about apples and oranges. Would-be paid medical leave takers outnumber new parents threefold. The former group are the focus of a companion bill to Gillibrand’s FAMILY Act, which has three times been introduced in the House of Representatives by Connecticut’s Rosa DeLauro. Where Gillibrand reps the maternal minority, the 14-term DeLauro speaks for the growing cohort of ailing seniors in our aging nation and their grown children who need time off from work to care for them. She was diagnosed with ovarian cancer while serving as chief of staff for former Connecticut senator Chris Dodd, and he provided her paid leave.

DeLauro applauds Republicans for coming around. “It used to be just the Democrats looking at these issues,” she tells me. “While I believe Donald Trump’s parental leave plan doesn’t go far enough, I welcome him to the conversation.” “Half measures”—an employer tax credit, a program for parental but not medical leave, or a refundable child-tax-credit expansion—aren’t worth the trouble, DeLauro warns, because they’ll let lukewarm advocates “check that box, and move on to the next thing.”

Deb Fischer scoffs at such reflexive opposition to a moderate answer to the universal mandates her Democratic colleagues seek to impose. She knows her bill covers nowhere near so many parents as Gillibrand’s federal mandate built atop Social Security, but for her a bill inoffensive enough to pass is a win. Considering what’s at stake, “I would find it very difficult to look a single mother in the eye and say, ‘Well, I didn’t vote for Senator Fischer’s bill so you could take a couple hours off to take your child to the doctor because it didn’t go far enough.’ To me that is a pretty weak excuse.”

The splash made by the Rubio-Lee plan didn’t escape paid family leave’s Senate Republican champion either. “Ivanka has focused a lot on the child tax credit, as have Senator Rubio and Senator Lee,” Fischer tells me, after running down a list of other proposals discussed at Rubio’s meeting—tax credits for home caregivers and for adoptive parents among them. To the extent that a tax credit substitution nods to stay-at-home moms, it’s worth remembering that they are more common in Lee’s Utah than any other state.

There’s certainly a give-me-liberty tinge to Senate Republicans’ nudging Ivanka to the right on the one fixed point in her legislative agenda. But conservative arguments for a comprehensive paid-leave program—one that would increase payroll taxes and wouldn’t even spare small businesses—are rising to the fore. A set number of even partially paid weeks of leave, studies show, make new mothers far more likely to keep up regular employment. Advocates like Abby McCloskey want to make lifting these women and their children from a lifetime of welfare dependence a rallying cry for fiscal conservatives.

And the burden on small business shouldn’t stand in the way of a federal mandate, former CBO director Douglas Holtz-Eakin said during a panel discussion that marked the AEI-Brookings proposal’s unveiling: “Exempting small businesses says to me, ‘Let’s have a tax on growth,’ ” he said—a disincentive for employers ever to grow beyond being a small shop. And, he added, “This isn’t about the employer. It’s about the kid. They are born to workers in small and large firms and we should care about them equally.”

SILICON VALLEY’S TRICKLE-DOWN EFFECT

In many ways, the market has already spoken. Silicon Valley has been host to a paid-leave arms race for years that, with flex schedules and work from home arrangements, set a social revolution in motion. In 2012, Google increased its paid leave for mothers from three to five months in response to internal findings that they’d failed to hang on to their female employees. The post-partum attrition rate halved as a result. In 2015, Netflix launched a thousand think pieces with a new policy offering paid maternity and paternity leave in the first year of a child’s life, even for hourly workers. The unlimited approach allows parents to work continuously in small batches during extended time off.

“The hardest part in a woman’s career is coming back after having a baby,” says Janet Van Huysse, a longtime Silicon Valley human resources manager who built Twitter’s benefits package for parents from the ground up. Her first child had just turned 1 when Van Huysse made her return to the workforce in 2009. Nascent 100-employee, zero-revenue Twitter was offering new mothers 12 weeks’ leave and fathers 6 weeks—now, it’s 20 weeks for all parents. When her second child arrived on the scene, five weeks early, Van Huysse worked right through her leave—a choice she advises against. “I use that as a cautionary tale for parents,” who, she tells me, haven’t figured out yet how much more their children need them than their company does. “You think that you’re so important, but you’re not going to be doing your best work. Plus, you’re never going to get this time back. Your baby’s never going to be a week old again, a month old again.”

The burden of putting a leave-length value on employees with families has fallen to young and highly competitive companies like Twitter. “It’s a reflection of your talent pool,” Van Huysse says, and it’s an investment in retention. “A 20-week absence is not a big deal when you’re looking at someone who you want to be a part of your company.”

Tech companies, competing to retain female employees and recruit the variously gendered, know that millennials are more than twice as likely as their elders to switch jobs in search of paid leave—as reported in Gallup’s 2017 State of the American Workplace. Savvy CEOs tout their escalating generosity in a game of corporate one-upsmanship.

In early 2017, Sheryl Sandberg, who’d earlier urged women to “lean in,” added 20 days of bereavement leave for any Facebook employee mourning a family member and longer for caring for a sick relative. She made the announcement in a moving public letter that invoked her husband’s sudden death and its toll on her young family. Facebook also offers fertility benefits—company money to fund in vitro fertilization and egg-freezing for career women who want to wait to have kids—and four months’ leave for new mothers and fathers, matching the tech industry average. Such policies and celebrity CEOs’ embrace of them are a publicity boon for these companies and help offset some of the bad publicity such corporate giants regularly incur for, say, a mishandled fake news scandal, the widespread hacking of user data, or, most commonly of late, repeat allegations of workplace harassment.

Whether employees actually use the full benefit remains a question. When they do, it’s often thanks to examples from on high, Telle Whitney, president of the Anita Borg Institute for Women and Technology, tells me: “Some of these younger companies, like Google and Facebook, as they started to mature and as they became bigger, created paid-leave policies that were very much appreciated by their workforce.” As their workers grew up, she explains, so did their policies. But, says Samantha Walravens, author of Torn: True Stories of Kids, Career & the Conflict of Modern Motherhood, “If the CEO or executives are not taking their leaves, then it’s sending a message to others at the company that it’s not okay to take your leave.” Mark Zuckerberg, for example, is on the cusp of his second two-month paternity leave, according to a recent post on his Facebook page. Marissa Mayer sent the opposite message in 2012 when, shortly after becoming Yahoo’s president and CEO while pregnant, she built a nursery off her office rather than take a full maternity leave (she took two weeks) or even work from home. Mayer banned remote work for Yahoo employees the following year.

Walravens praises one CEO friend, a notable anti-Mayer. Julia Hartz cofounded the online ticketing company Eventbrite with her husband in 2006 and had her first child in 2008, just when they were looking to hire their first employee. “I was always on my computer in the hospital, and the nurses threatened to take the computer away and move the baby to the nursery,” she recalled in a 2010 interview. “I did not unplug from the business, but I did not go back to the office until I was ready. I worked from home for five months.” In the years since, she’s had a second child and, in 2016, became Eventbrite’s CEO. Hartz worked from home every Friday and leaned on her mother and a nanny when her first child—and her company—were young. She is today a vocal advocate for employees taking their leave and only easing back into work. In Walravens’s words, Hartz “walks the talk.”

So it is that the same Silicon Valley innovators whose revolution outmoded domestic tranquility have also done the best job demanding and receiving time off to take care of their families.

MAKING ENDS MEET

Unlike in the past, there is increasingly little difference between home and office. “Today I can do most of my work from my phone—sadly,” says Van Huysse. The same conveniences that permit the plugged-in home office require parents to respond to their colleagues’ emails after putting their children to bed. Our banker Jane remembers waking up in her son’s room many hours after his bedtime with her phone furiously pinging in her hand. A young trader was waiting for her signoff on a client presentation.

A mother or father at home during the day is likelier than ever to be working remotely, from a laptop at the dining room table or at a standing desk in the den. Flexible scheduling, telecommuting, and family-friendly hours are common in businesses big and small, according to Lisa Horn, who lobbies Congress for the Society for Human Resource Management. Employees value the freedom to choose their hours and the availability of paid family leave almost equally in rating their benefits, according to a recent Pew survey: 28 percent cite flexible hours first, 27 percent paid leave.

The growing population of work-at-home parents toil in service to an inflated cost of living. The American middle-class family needs as many salaries as it can get today. Yet the benefits of work’s encroachment into life’s domain may outweigh the losses. Talented women who would, in generations past, have been cowed into the kitchen by convention are maintaining their careers. And men who’d have missed their children’s fleeting early years can be present where they would have been absent without getting off the advancement track.

When they first moved to Silicon Valley in the mid-1990s, Van Huysse and her husband worked long hours on bulky desktop computers. Today’s increasingly mobile worker has less and less need to be in the office. Sounding not unlike a Republican lawmaker extolling the virtues of a child tax credit expansion, Van Huysse says, “I want everyone to be able to have the flexibility to make the right choices for themselves and their families.”

AN ISSUE WHOSE TIME HAS COME?

For now, the manifestations of a universal work-life imbalance differ widely enough that sensible people sniff at a socialite like Ivanka Trump’s advocating for working women. Ever on-brand, she takes to Twitter to congratulate hedge funds that roll out revamped paid-leave packages. It’s easy to say each child deserves as much nurturing as possible in his first weeks of life, regardless of where his parents work. But “work-life balance” and paid family leave and pro-family policy translate differently for every profession—and from every advocate’s vantage.

Regardless, it’s An Issue Whose Time Has Come—at least according to the tagline for the AEI-Brookings plan. But so said nearly everyone I talked to on the subject this summer. The time has come to talk about it, to consider what it means for American families and why more than 80 percent of them want Congress to move on the issue. We have to ask and answer how long leave should be, who’ll get it, and—the thorniest thicket of all—who’ll pay for it and, by Grover, how.

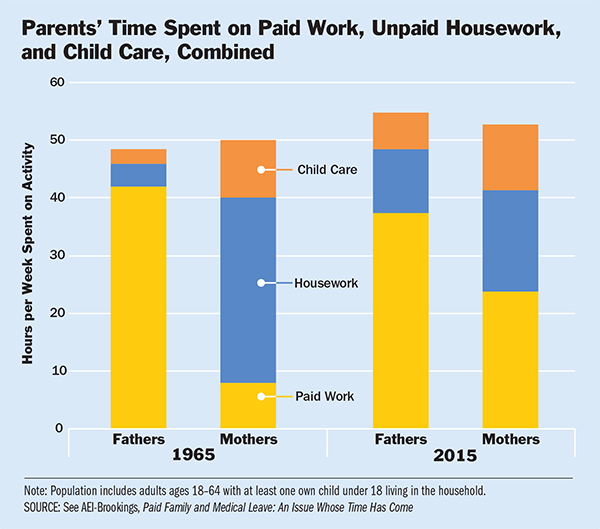

Stacey Manes, another Silicon Valley human resources pioneer who now coaches women in tech on pursuing leadership roles and competing with the dominant “tech bros,” tells me about her mother. “I grew up in a household where both parents worked, and my mom definitely carried the bigger share of the laundry, cooking, and cleaning. How in the world did she do it? She worked full-time.” But, Manes realizes, it was an era with very different expectations from the one whose unceasing demands she has built her career helping hardworking men and women manage.

At first, she puzzled over her mother’s superhuman ability to run a household and hold a job—then, “It dawned on me that she never brought her work home. She was an office manager for a dentist. The day actually ended at 5 o’clock.” And, once again with the recognition that the time has come, she says with a note of mourning, “That’s just not the world we’re living in anymore.”

Alice B. Lloyd is a reporter at The Weekly Standard.

*Correction appended, 8/25/17: The quotation was originally misattributed to Jane Waldfogel.