Politics and theater have a lot in common, not least of which is the tendency of people involved in both to overuse certain labels. No theatrical concept has fared worse on this front than “Method acting.” For even the casual moviegoer, the phrase immediately calls to mind Leonardo DiCaprio eating bison meat or Daniel Day-Lewis refusing to break character between takes. You hear “Method acting,” you think pretentious.

But these practices are only distantly related to “the Method,” an acting style born in Russia and developed in America throughout the 20th century. There are a number of reasons this specific school of thought has become a byword for all sorts of affectation, but the biggest is this: Even among its founders and most notable practitioners, no one can fully agree on what the Method is.

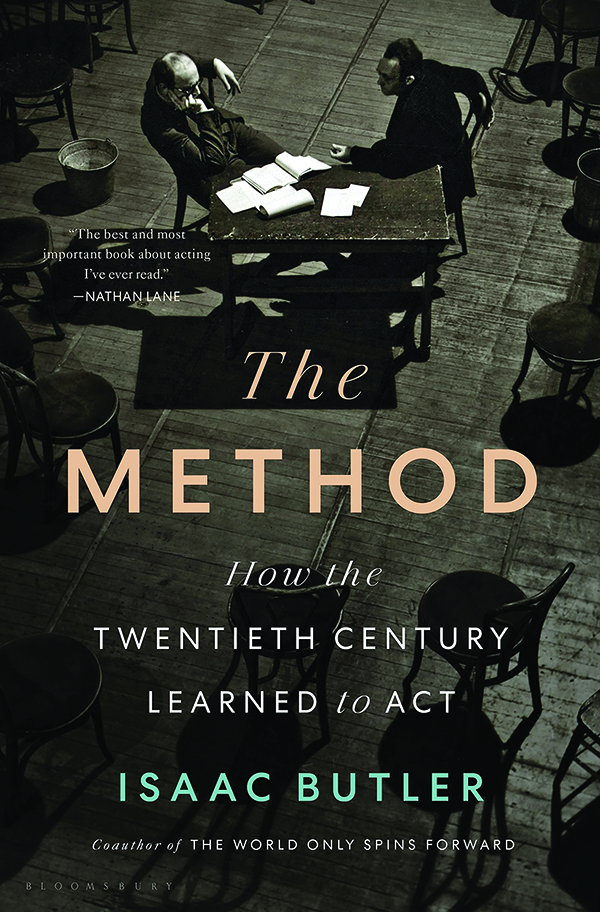

In The Method: How The 20th Century Learned to Act, Isaac Butler attempts to shed light on this elusive idea. A theater critic and professor at the New School, Butler has written an engaging and accessible account of a niche, complicated subject. In doing so, he dispels common misconceptions about the Method and shows just how much 21st century actors owe to a handful of acting teachers and their esoteric ideas.

Long before Americans practiced the Method, a cadre of Russian actors studied a new acting philosophy conceived by Konstantin Stanislavski in the late 19th century. A character actor from a wealthy family, Stanislavski felt trapped by the state of Russian theater. Not only were productions disconnected from reality, but actors were disconnected from what Stanislavski felt was a “sacred task.” In 1898, Stanislavski founded the Moscow Art Theatre and began training actors in his then-radical style. Stanislavski “appointed himself the scourge of hokum, nixing the booming voices and operating gestures” that characterized Russian theater. Instead, he encouraged actors to connect with their characters and perform in an authentic, realistic way. It was during this time that Stanislavski began developing the abstract concepts that would come to comprise what he called “the system.” He believed actors deliver truly good performances not through affectation but by entering the “creative mood.” Stanislavski held that the “creative mood” could only be entered if actors tapped into their “superconscious” by mining their personal experiences for inspiration.

Harnessing the power of “affective memory” in turn required that actors put their roles together bit by bit, through script study, research, emotional exercise, and more. The ultimate end of the system was perezhivanie, or experiencing, which Butler helpfully defines as “a state of fusion between actor and character, a merging of the two selves.”

These concepts are weighty and open to interpretation, in a large part because Stanislavski did not write on “the system” until later in his life and often contradicted himself on his own teachings. The ambiguity this creates will forever remain part and parcel of the Method. Butler does a fine job opening Stanislavski’s world and ideas to a wider audience. Still, early 20th century Russian theater is not the most exciting subject. Fortunately, The Method really begins to pick up steam when the Russian Revolution forces “the system” and its practitioners to take refuge in America.

Members of the Moscow Art Theatre began making their way to the United States around 1920 and immediately began teaching versions of Stanislavski’s system along with their own acting philosophies. In 1931, a group of Stanislavski’s intellectual grandchildren founded a theater collective in New York City. The Group Theatre synthesized the various Russian acting theories and dubbed it “the Method,” which they felt sounded less totalizing and pretentious than “the system.” Among the collective’s founding members were Lee Strasberg and Stella Adler, whose lifelong feud would change the state of American acting. There was no shortage of kindling for the enmity the pair held for each other. Strasberg was a neurotic upstart actor whose theatrical career began when he studied with students of Stanislavski. Adler was the scion of a Yiddish American acting dynasty who was skeptical of the Method from the beginning. Both were intense, and neither was very likable.

But their true clash was a matter of interpretation. In 1934, Strasberg and Adler made a pilgrimage to Moscow. Adler met with Stanislavski and claimed the master disavowed Strasberg and the Group Theatre’s reliance on memory and emotion. For his part, Strasberg was shocked to find the Moscow Art Theatre had abandoned Stanislavski’s system to the company’s detriment and resolved to double down on the very principles Adler was determined to purge from the Group Theatre. For the rest of her life, Adler would argue that an actor’s imagination was the key to an authentic performance. Strasberg maintained that actors genuinely needed to feel a character’s emotions to perform well. They never found common cause. When her lifelong rival died in 1982, Adler told her students, “It will take the theatre decades to recover from the damage Lee Strasberg inflicted on actors.”

Butler parses the Strasberg-Adler feud in detail, helpfully retreading their philosophical differences over and over again. It’s a fascinating study in how intellectual movements splinter. But more importantly, it shows that, from the audience’s perspective, the differences between the various submethods are irrelevant. What matters is the broad emphasis on the type of “authentic” performance that enabled actors to carry the realistic plays and films that would come to define America in the 20th century.

It’s now impossible to think of the Method without thinking of Marlon Brando, who was propelled into superstardom by his turn as Stanley Kowalski in Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire. Williams, an Actors Studio alumnus, gave Method actors ample opportunity to channel “authenticity” with his raw, morally ambiguous script. Both the play and its film adaptation were directed by Elia Kazan, a Group Theatre alumnus and Actors Studio co-founder. The publicity surrounding Streetcar entrenched the Method in the popular consciousness. And, in Butler’s telling, the Method displaced the Old Hollywood consensus with the 1972 premier of The Godfather. “To buy a ticket to The Godfather,” he writes, “meant that you would see … Marlon Brando’s passing of the Method torch to a new generation.” The film’s leads were all Method actors, most notably Al Pacino, Strasberg’s favorite student. By the time Adler’s pupil Robert DeNiro played a young Don Corleone in The Godfather: Part II, the Method had joined the ranks of what Butler calls “the Big Ideas of the twentieth century.”

Like many of these Big Ideas, the Method’s success made it a bigger target for critics. This likely inevitable process was accelerated by two factors. The first was Hollywood studios’ decisions to build marketing campaigns around Method acting. The second, related point was the growing number of actors whose antics were ascribed to the Method, though they were anything but. This is one of the most interesting parts of the book — and certainly the one with the most contemporary relevance. Unfortunately, Butler speeds through this section, leaving more questions than answers. He makes it clear, for instance, that Dustin Hoffman’s notorious antics while remaining in character on set, including slapping Meryl Streep to provoke real tears or going on a bender to appear disheveled, is not even close to Method acting, properly understood.

But Butler does not explain why so many extreme behaviors became associated with the Method, nor how they became so popular among a new generation of American movie stars. It’s likely bound up in Hollywood marketing departments’ Method-centric campaigns, but Butler leaves it open for speculation. It’s a disappointing unspecificity in a book whose only other weakness is a tendency to overexplain.

In a way, the Method has come full circle since Stanislavski first cooked it up at a Moscow cafe. Then, as now, it was a niche and misunderstood theory practiced by a handful of dedicated actors and roundly mocked by the mainstream. But along the way, the Method rewired American acting. Like socialist activists who get rich criticizing capitalism, the majority of people who mock the Method today do so using ideas and vocabulary inherited from Strasberg and Adler.

Tim Rice is associate editor of the Washington Free Beacon.