Dave Howe is in a private air terminal on a cold, wind-swept morning in Amarillo, Texas. He’s looking out the window at the massive wings and engines of Fifi. Silvery, aluminum Fifi. She’s the last flying B-29 Superfortress in the world, and Howe’s got a ticket to ride.

Howe, 71, looks out at the bomber in a way that brings tears to your eyes. He chokes up just trying to discuss what he’ll be feeling once he’s up close.

“None of us felt like we could afford to do this,” Howe says, motioning to his sister, brother and nephew, who are boarding Fifi with him. But Howe’s wife insisted, once she saw the look in his eyes when he heard the B-29 was coming.

“She said, you’re going on that flight. We’ll find the money. You’re going.”

Howe’s need for the flight is tucked under his arm. An aging, framed photograph, taken Aug. 6, 1945. In the photo, Howe’s shirtless 25-year-old father cocks his head and squints into the sun, with the Enola Gay behind him.

“The plane had just landed from the Hiroshima [atomic bombing] mission when this picture was taken,” Howe says. His dad, a radio operator on the crew of another B-29 on base, couldn’t resist getting a photo to mark the historic moment. The back of the frame tells the rest of the story: “8-6-45. Tinian Island, Pacific Ocean. Staff Sergeant Clarence M. Howe Jr. The engines were still warm.”

“Several of them took pictures with it,” Howe says. “Then, some colonel got nervous and they threw tarps over it and brought MPs out and squirreled it away.”

Howe is one of the lucky ones — his father at least talked about the war. So many more of Fifi’s visitors know their fathers or grandfathers flew in World War II, but little else. For them, a visit to Fifi is the closest they will ever come to understanding what their family went through. They look to Fifi’s crew for answers to questions they never got the chance to ask.

“This airplane has a soul,” says Kim Pardon, who is one of the 150 volunteers, the “crew” who help keep Fifi running. “We try to be true to that soul by telling her story.”

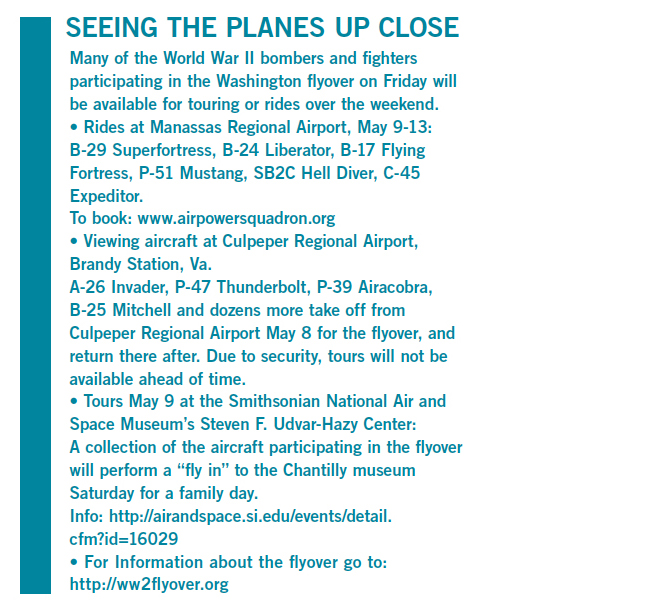

Fifi is one of more than 60 vintage World War II fighter aircraft, transport planes and bombers that have committed to participate in a once-in-a-lifetime flyover of the National Mall at noon on May 8.

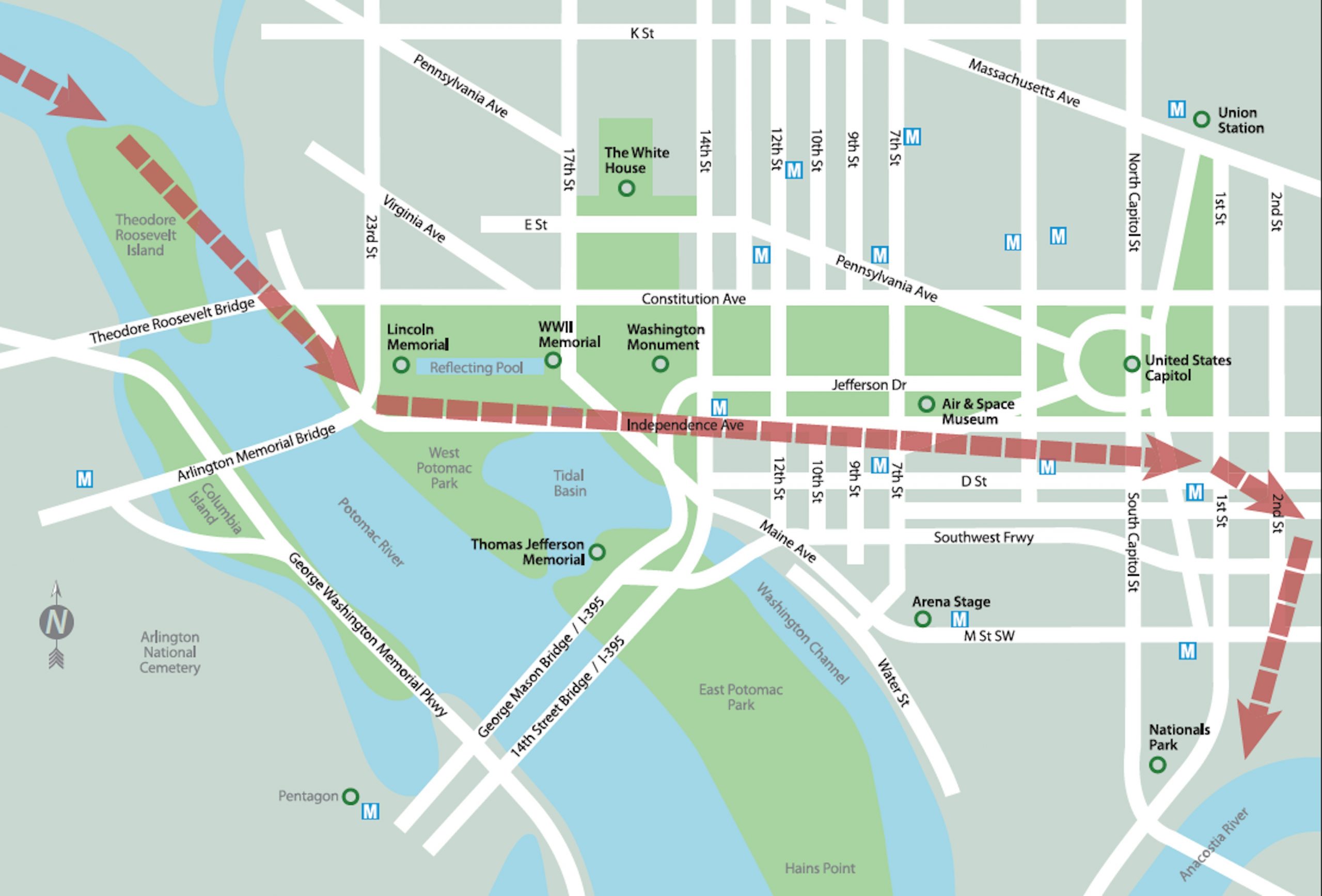

They’ll fly in low and close, in waves of four planes each that will parade 1,000 feet above the Washington Monument, the Lincoln Memorial and the National World War II Memorial. They will fly that low to let the last surviving World War II veterans gathered at the memorial hear and feel their engines in an airborne tribute to the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II. At the end of the ceremony, the last wave to pass over the veterans will fly in a missing man formation, to salute the more than 400,000 U.S. troops who died in the war and the millions of veterans who did not live long enough to see the commemoration.

“This is all about saluting the veterans,” says event organizer Peter Bunce, a 26-year Air Force A-10 and F-15 pilot.

Vanishing generation

Not many WWII veterans are left. Of the 16 million U.S. service members from World War II, about 850,000 remain. Most of those vets are in their late 80s or early 90s. About 300 to 400 are expected to be in Washington for the flyover.

May 8 is the 70th anniversary of Victory-Europe Day, the day the Allies accepted the terms of Nazi Germany’s surrender in World War II. While it took until August 1945, and the atomic bombs dropped by the B-29s Enola Gay and Bockscar to defeat Japan, the May date was picked to avoid D.C.’s infamous summer heat and make the trip as accommodating as possible to the veterans, Bunce said.

The handful of vintage aircraft organizations who preserve military flying history have spent the last year working with the Secret Service, Federal Aviation Administration, Transportation Security Agency, National Park Service and local airports to clear a route that will take them down the Potomac River and over the Mall, the heart of Washington’s most tightly restricted airspace.

Besides the security quandaries, there are concerns about the vintage aircraft, too. They will need good weather and visibility on the day of the flight. If the weather is not accommodating on Friday, the flight will be rescheduled for Saturday.

Like the veterans who flew them, most of World War II’s bombers are gone. More than 3,500 B-29s were built to fly in World War II and the Korean War. But only Fifi still flies. She’s one-half of the B-29/B-24 Squadron based in Fort Worth, Texas, where the vintage warbirds share crews, maintenance, volunteers and a hangar.

Fifi’s other half, the B-24 Liberator Diamond Lil, is almost as rare. Of the more than 18,000 Liberators built in World War II, Lil is one of only two still flying.

Both planes are part of the larger Commemorative Air Force, a group that was founded in the 1950s when a bunch of pilots got heartsick at the thought of the former warbirds being recycled into aluminum ingot “to make beer cans,” group president Steve Brown said. They collected $1,500 and bought their first P-51 Mustang from the Air Force.

“And the warbird movement was born,” Brown says. One by one, they added to their fleet. Fifi, for example, was found at a Navy base in California, where she was to be used as a missile target.

Now the Commemorative Air Force has 162 planes that are based at volunteer squadrons throughout the country. The group has restored WWII fighters such as the P-51 Mustang, the P-40 Warhawk and the P-47 Thunderbolt, and bombers such as the B-25 Mitchell made famous by the Doolittle Raid, the B-17 Flying Fortress and the B-24 Liberator.

These aren’t static displays, either.

“We believe in flying our aircraft,” Brown says.

Patience, time and money

To keep each warbird in the air requires time, money and a fiercely loyal body of volunteers. It also requires patience, camaraderie, a sense of humor, a bit more patience and understanding significant others.

Of the volunteers who keep Fifi and Diamond Lil running, only a handful are “die-hards,” members who are with the aircraft basically as full-time volunteers, on the road for weeks at a time, living out of hotels and restaurants as they fly the bombers from state to state. Nobody draws a salary except for a few full-time mechanics the organization hires. Everyone else works for free, in response to a calling they’ve all heard.

“I always said I wanted to do this, but you have children and family and you work. I got away from it, but it’s always in the back of your mind,” says Curtis Wester. Wester’s dad was a barnstormer in the 1930s and would take his young son flying with him. Wester first saw Fifi in 1978. His thought was, “Man, I want to fly on that. And it took me 36 years to get there, but I did it. I did it.”

They do it for the effect they see the plane has on veterans, and now, as veterans die, on their adult children. It’s what crew member Phil Pardon calls “getting rid of a few ghosts.”

“You never know when something you do will change a person’s life,” adds crew member Jim Harner. A veteran will come aboard, and “they’ve not spoken to anybody about the war in 60-65 years. And you realize that being in the airplane has brought them back.”

On one tour stop in Punta Gorda, Fla.,”this guy walked up, maybe in his early 50s, and he was carrying a bag of pictures and papers and stuff,” Kim Pardon says. “He said his father had died before he was born. So there’s the huge line to get into the B-29 cockpit but we immediately took him to the front. Took him up and he sat in his father’s seat. And he just cried. And Brad Pilgrim [another volunteer] said, ‘You can sit there as long as you want to.’ He was there for quite a while.”

These days the crew doesn’t see as many World War II veterans. But they get scores of kids, a generation that has never seen a plane this big run on propeller engines.

Amarillo is the last stop for this six-week tour before the crew begins to prepare the planes for their historic flight in Washington. The last tour group of the day, as Amarillo melts into an early spring sunset, is a gaggle of teens and pre-teens from a nearby Civil Air Patrol unit. The kids line up, grinning in uniform alongside Fifi’s nose before scattering to climb into the fuselage.

A hardcore group

After closing time, at the end of a long day before their final dinner together, the crew still has one labor-intensive task ahead: Move Fifi about a quarter mile to a wider tarmac and park her for the night. From start to finish, it takes more than an hour. The crew has to be meticulous with even the smallest moves of their 71-year-old charge. Taxiing with just a few turns nevertheless requires that they run through a full pre-flight checklist before firing Fifi’s four thunderous engines.

“You don’t do anything fast in this airplane,” co-pilot Al Benzing says. Outside the window, a fire truck idles nearby, ready in case an engine catches fire.

Besides patience, perhaps the most important quality for a crew member is acceptance that a 71-year-old aircraft is likely to do what it wants and that you’re just along for the ride.

Over the years the crew has made only a few modifications. Five years ago, they replaced Fifi’s original under-performing, fire-prone, engines, which flight engineer Shad Morris calls “the junkies.” But otherwise, from the B-29 logo in the wheel to the block lettering on a wall of indicator lights and levers, Fifi’s almost completely restored parts are original.

Except the “turbulence indicator,” a dancing Hawaiian dashboard girl whose grass skirt bobs as soon as Fifi’s engines begin to shake and rumble.

“Required equipment,” says Benzing, smiling. “You ought to see the one we have on Lil.”

“All these old airplanes – there’s something about them,” Morris says. “They all smell the same. They almost all sound the same. They feel the same and they are all kind of built the same … in the sense that they weren’t supposed to be flying 75 years later.

“Cars rust. Tools will rust when they get old. Airplanes will too. They will corrode. They are not designed to be around that long. But thanks to technology and the devotion of this really hardcore group of people that you’re sitting with right here,” Morris says, waving his hand over the rest of Fifi’s crew. “This is the hardest of the hardcore. Just really burned up with it. I think that’s the key to keeping them flying. Obviously it does take a lot of bucks. Money does make the world go round. But it’s all for nothing if you don’t have the really passionate, hardcore people that are doing it for free, or most of it.”

During the plane’s move, Morris, lead pilot Paul Stojkov and Benzing work through Fifi’s pre-flight checklist, increasing power to each engine to run all four through accelerating rotations per minute, and listening for any problems. Without a headset, you can barely hear your own voice above the sound.

“Number one is not happy,” Stojkov notes.

Finally, Benzing calls out to ground control to request permission to get moving.

“Superfortress 529 Bravo, roger taxi,” control responds.

Fifi lurches forward and vibrates under her own weight.

“Boy, the little kids out there are jumpin’ and runnin,” Stojkov says, looking over his right shoulder and through Fifi’s glass-enclosed nose. Just outside the flight line, a bunch of Amarillo school kids run along the airfield’s chain link fence, lit gold by the sunset. They wave their arms and holler out as Fifi rolls past.

An hour later, once the plane is parked and locked and an entire post-flight rundown has been completed, the crew is … starving. They head to Jorge’s Tacos Garcia, a popular Amarillo restaurant that has pushed together four tables for them. The storytelling begins over margaritas and platters of cheese enchiladas.

Finding new recruits

One of the topics is how to get new members. Of the volunteers who understand and love the aircraft, not everyone has the ability to take the time off or has the resources to fly the tour.

“That’s the big thing,” Benzing says. “You have to be available. And you have to be able to get along. It’s long, hard, days, and you’re going to be out for weeks at a time. Not everybody does well on that.”

The group needs new pilots, ground crew and maintainers. Benzing, a retired commercial pilot, can count on his hands the number of pilots rated to fly both Fifi and Diamond Lil. And only half of those pilots are available to tour, he says.

“We’re always looking for new people, because it’s hard to find people that meet all the requirements,” Benzing says.

To keep a steady flow of future crews, the Commemorative Air Force is opening a warbird flight school in its new national headquarters at Dallas Executive Airport, to get interested pilots started on their single-engine vintage aircraft and get new blood flowing in the organization.

The squadron also runs ground schools, so it can increase the number of members who can volunteer to keep both types of aircraft flying. One hour of flight for Fifi costs more than $12,000 in fuel and operating costs and requires roughly 100 hours of down-time maintenance. Diamond Lil costs a bit less to fly, but not much. So both airframes’ lifeblood is the volunteer labor force that keeps them touring. A 30-minute flight on Fifi starts at $595 and goes for upwards of $1,400, depending on which of the 10-seat positions a passenger wants; Diamond Lil’s seats start at about $400. The crews try to keep the planes on the road as much as possible to earn the money to keep them flying.

“If you can turn a screwdriver they’ll give you something to do,” says Jim Neill, 75, one of the tail section scanners. “If not, they’ll give you a mop and a broom.”

Years ago, some of the crew saw Neill admiring Franklin Mint die-cast models of bombers in a store and asked if he had thought about working on the real thing.

Now he’s a “die-hard.”

“I have two mistresses,” Neill says. “Fifi and Diamond Lil.”

While the rest of the crew is celebrating their last night on the tour, new recruit Todd Erskine is thinking ahead to the morning flight home — his first as a crew member. Most of the volunteers have at least a decade over Erskine, a young nuclear engineer who saw Fifi and bought a commemorative ride last year in honor of his late U.S. Marine Corps grandfather, Master Tech Sgt. Robert Erskine, who died in 2010.

The elder Erskine was a mechanic with VMF-124, a Marine fighter squadron of Corsairs that were sea-launched from U.S. aircraft carriers and attacked enemy aircraft and ships in the Pacific.

After that first paid flight as a passenger, he decided to volunteer for some of the bomber’s winter servicing. And then he was hooked. It was time to become a full crew member.

Erskine has no flight training, so he’s been studying the duties of the scanner role, such as making sure the engines are clear, and running the long-line between the ground crew and the pilots that allows them to communicate as Fifi is firing her engines.

“The reason I started out with the Commemorative Air Force is really [for] remembering my grandfather and his generation, and what they did with what they had,” Erskine said.

Inside the B-29, there are seats for eight in the front, but it gets tight fast when more than two people try to move around at once. A long, skinny tunnel connects the nose to the tail section, where three crew member “scanners” sit. The rest of the tail section seats are kept open for paying passengers.

“They are the only ones who can see our [landing] gear, our flaps, smoke from the engines and oil leaks,” Benzing said. The tunnel connecting both sections is only wide enough for one person at a time to shimmy through, but that tunnel design was what allowed the B-29 to keep a pressurized cabin while dropping bombs.

Spending all day with the crew, staying together for meals at night, you have to have camaraderie. On the flight home, when at 7,500 feet, Morris “asks” the crew in the back whether they are cold.

“How are you guys doing in the back”? Morris calls out.

“We are doing fine,” they says over the headsets.

“Is it cold back there?’

“No it’s fine.”

“How about now?” Morris plays, opening the air intakes and blasting his friends with a frigid gust.

“Hey!!”

One of the trademark characteristics of the Superfortress is her globe of glass at the cockpit, giving the bombardier and pilots a 180-degree view.

It creates an odd juxtaposition: As Fifi turns to the runway for takeoff everything shakes. Metal seats and storage boxes rattle — but the view through the glass nose is perfectly still.

Morris pushes the throttle to full and the center line starts to ribbon away into a fast blur as the violent energy of Fifi’s propellers gathers speed and launches her into graceful flight.

Once airborne, Fifi’s engines still deafen and her whole body still squeaks — but even after 71 years there’s a smoothness to the miles and dotted clouds passing underneath her that can rival today’s commercial flight.

Homage to history

While Fifi, the more modern B-29 “flies more like a Boeing,” the Liberator … “that one flies like … something else,” Benzing said.

The Boeing-built B-29 Superfortress is famous for ending the war, while the Consolidated-designed B-24 Liberator is famed for pounding targets like a heavyweight boxer. Crews of 10 or 11 men would ride cramped and cold to make space for the Liberator’s 8,000 pounds of bombs. Diamond Lil is a B-24A model, one of the earliest, and she is an unwieldy creature both in taxiing and flight. Benzing regularly has to push back when Lil “seemingly of her own volition” noses up or fights to drift off course.

“I would hate to have to fly her in formation,” Benzing says about the U.S. Army Air Forces pilots and crews who did, flying 14 hours at a time in heavy clouds and terrible weather, required to hold tight diamond-shaped formations to defend against enemy fighters. Liberator pilots were often known by their swollen left-arm muscles, developed from hours of gripping the wheel left-handed.

On tour, Lil has always been in the shadow of the shinier, sleeker Fifi, and during World War II, could never garner the attention that the B-17 Flying Fortress did. That has changed with the publicity generated by the life story of B-24 bombardier, crash survivor and Japanese prisoner of war Louis Zamperini in the bestselling book and 2014 movie “Unbroken.”

On May 8, one of the waves of planes that fly over Washington will commemorate the deadliest B-24 run of the war: the Aug. 1, 1943, over Ploesti, Romania. For weeks before that raid, scores of U.S. B-24 crews practiced flying 100 feet off the ground over their bases in North Africa. They flew that riskily to be ready for a surprise attack against Hitler’s main oil refineries in the town. But the Nazis got wind of their plans, and the attacking force was met by prepared enemy fighters, smoke screens and heavy anti-aircraft fire. B-24s were cut in half by attacking aircraft and spun out of control to the ground.

Morris looks at some of the historic paperwork from that day to put it into perspective.

“Took off at 7:00 [a.m.] At 9:05, saw B-24 explode and crash giving off black smoke. Continued on,” Morris reads from a mission report from the deadly raid. “That’s just two hours into the mission. They ain’t even there yet. 12:10 p.m., 240 feet.”

“Two hundred forty feet?” another crew member asks, incredulous.

“Yep,” Morris continues, “saw two B-24s headed nose over into the ground.”

Time to fly

The last morning of the tour, Fifi has two more honor flights to make and then she will head for home. But the weather is not cooperating. Strong wind gusts buffet the plane and threaten to keep it on the ground even as its giddy 9:30 a.m. passengers admire her from a distance.

It’s here where Dave Howe is looking out the air terminal window, hoping he will fly today.

The hours pass, giving the roomful of passengers time to get to know each other. It gives Howe a chance to walk out to Fifi up close and stand where his father stood 70 years ago.

In the cold, Howe rushes up to the fuselage.

“Hello, old girl,” he says, with a forceful, emotional pat of her siding.

Dave Howe’s father, Clarence, was a radio operator with the 444th Bomb Group at Tinian Island. He didn’t like to be called Clarence, so he went by C.M., and he didn’t care much for authority. He ended the war a master sergeant, but not before getting demoted and re-promoted three stripes during his time of service.

Dave Howe has his father’s streak in him, and it took until he was almost 26 before father and son could see eye to eye. “He and I had just made friends,” Howe says, eyes welling. “I was grown up by then and all the teenage angst was behind us and all that stuff. And he got killed.”

Dave’s father died in a car accident in 1970.

“That was the biggest loss in my life — him getting killed at that particular time.”

At 11:30 a.m., the crew is still in an adjoining conference room at the private air terminal, watching as the temperatures and cloud ceiling lift. The winds are finally giving way, so Stojkov begins to give the pre-flight brief, which begins with reminding passengers of the past.

“When you’re up there today, it’s a beautiful day in Amarillo.” Stojkov says. It wasn’t like this in the war. “Think about what it must have been like back in ’44, ’45, being 18, 19, or 20, scared out of your wits and somebody is trying to kill you, literally trying to kill you.”

Dave Howe’s younger sister, Sue Montgomery, is imagining it. She’s standing beside a new friend, Korean War veteran LTJG Ed Bethel, a VF-781 pilot assigned to fly Grumman F9F-5 Panthers off the aircraft carrier USS Orsikany from 1952-53. Bethel traveled for hours to make this flight, and is alone. As he waits for the bomber ride, he tells war stories, including the two times he had to eject from his aircraft — once busting right through the Panther’s canopy.

“Thank you for your service,” Sue says, her blue eyes welling like her brother’s.

Finally it’s time to fly. The air terminal opens, and the crew asks if everyone has someone to walk out with to Fifi.

Sue takes Ed’s arm. “My adopted family,” she says. And together they step into the Amarillo sunshine toward their bomber.