Marco Rubio’s presidential campaign, and perhaps his political career, ended in ignominy Tuesday after a crushing defeat in his homestate of Florida at the hands of Donald Trump.

The charismatic freshman senator began his campaign last year with many Republicans believing he had a strong chance not just of uniting the party but also of going on to beat Hillary Clinton.

But on Tuesday night, in abandoning his White House bid, Rubio said: “This may not be the year for a hopeful and optimistic message.”

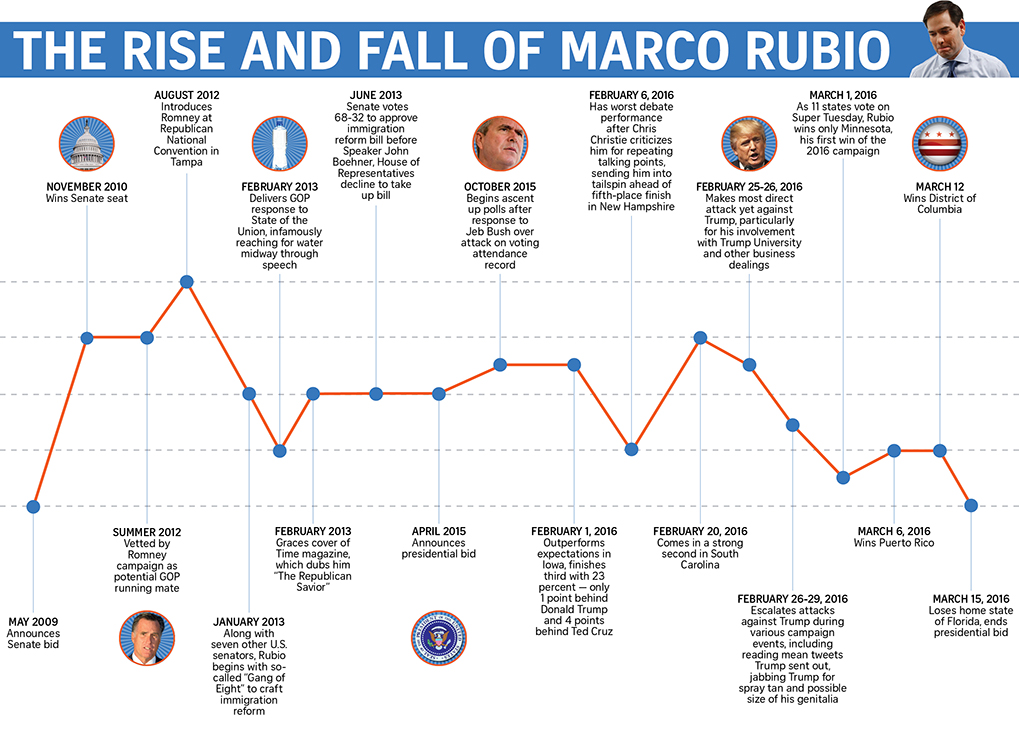

His dramatic rise and fall has been genuinely meteoric.

A one-time darling of conservatives, Rubio came to the Senate as part of the Tea Party wave in 2010. As the son of Cuban immigrants who is fluent in Spanish, Rubio was seen by many political observers as the future of the Republican Party in a nation undergoing rapid demographic change.

His inspirational speeches drew comparisons to the Barack Obama of 2008. But after a flirtation with Democrats on immigration reform, some strategic miscalculations, and taking around $50 million in heavy fire from his GOP opponents, Rubio struggled to find a constituency for his optimistic message at a time when the electorate was more animated by anger against political elites.

Having declined to run for reelection to the Senate, he’ll find himself out of political office by early next year. Rubio’s future prospects were uncertain following Tuesday’s loss.

“Rubio represented what many people have said should be the future of the GOP. Unfortunately, the party tends to pick its fruit before it’s ripe,” said Isaiah McGee, an Iowa Republican who backed the senator. “Ironically, he was cast as the establishment candidate, when in fact he would’ve been more conservative than the establishment would’ve liked. It’s probably also the reason why he struggled.”

Rubio didn’t make many mistakes or commit serious gaffes in a presidential campaign that lasted a year — though when he did stumble, as in the debate leading up to the New Hampshire primary, he did so badly and it proved costly.

The politically gifted senator ran a mostly disciplined campaign, generally excelled in the televised presidential debates, and maintained high approval ratings and competitive poll numbers despite enduring tens of millions of dollars in negative attacks from his Republican competitors, more than any other candidate in the original field of 17. But in the end, Rubio just couldn’t win enough votes, where and when he needed to.

These results could be attributable partly to Rubio’s lead role in negotiating the bipartisan, “Gang of Eight” comprehensive immigration reform legislation. The bill, which passed the Senate but stalled in the House, would have provided a path to citizenship for some illegal immigrants, an apostasy that some GOP primary voters found unforgivable. They also could be due to his opponents highlighting his lack of executive experience and the trouble some of his supporters had in identifying his accomplishments as a legislator.

Data curated by InsideGov

As the losses in primaries and caucuses mounted in March, an avalanche of bad press and the reality that Rubio’s path to the nomination had virtually vanished crushed a candidate that had until then so adeptly managed expectations and the media narrative surrounding his campaign. It was a disappointing end to the 44 year-old senator’s White House bid.

Rubio’s campaign began with so much promise. He delivered a rousing speech, rich in classic, American themes of confidence and optimism about the future, from Miami’s historic Freedom Tower, once referred to as the “Ellis Island of the South” because it processed so many Cuban immigrants like his parents. By the time Rubio’s campaign ended, he would only win Minnesota, Puerto Rico, and Washington, D.C., coming in no better than second in the crucial early primary states.

“He had no true base,” McGee lamented.

In hindsight, Rubio could have chosen a more successful strategy to carve his path to the 2016 nomination.

The Floridian possibly might have performed better if he had deployed a stronger grassroots operation in the states that were favorable to him and that he needed to win. The trajectory of the Rubio campaign might have headed upward had he scored just a few percentage points better in Virginia on Super Tuesday. Instead he came up short — yet again, this time to Trump — and the senator’s March death march continued.

But viewed another way, Rubio surviving as long as he did, becoming one of the final four candidates to contend for the nomination, was somewhat remarkable, a testament to his resiliency as a presidential candidate. Trump, the New York celebrity businessman, has been in command of the race since July. But it’s Rubio whom the rest of the field treated as the frontrunner that stood between them and the Cleveland convention.

In more than one presidential debate, it was Rubio, not Trump (or Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas,) who had to fend off multiple attacks from multiple candidates. It was Rubio, not Trump or Cruz, who endured $27 million in attack ads from Right to Rise USA, the super PAC supporting ex-Florida Gov. Jeb Bush. Another $9 million or so was thrown at Rubio by the collection of super PACs supporting Cruz, led by Keep the Promise I.

All told, the Rubio campaign estimates that the senator’s opponents spent more than $50 million to knock the Floridian out of the race, including $15 million in Iowa alone.

Still, Rubio defied expectations to finish third in the Hawkeye State, just one point behind Trump. He surpassed projections again in South Carolina, garnering second place, ahead of Cruz. Rubio finished a disappointing fifth in New Hampshire but came in second in Nevada — again, ahead of Cruz. At this point, heading into the March Super Tuesday primaries, the political chatter about who should drop out focused on underperforming Cruz.

“No other candidate has endured the level of attacks launched against him by both Republicans and Democrats,” said Adam Hasner, a Republican former member of the Florida legislature who has backed Rubio since his campaign began last March. “Through it all, Marco’s faith has ensured that he has maintained an unrivaled level of personal strength and confidence that is truly inspiring.”

From its inception, Rubio built his campaign around the goal of becoming the consensus Republican as other candidates dropped out or were deemed unacceptable for some reason or another. The senator would run on the sunny slogan that the U.S. was one election away from turning what has been a challenging first 15 years of the 21st century into a “new American century.” The 20th century is often referred to as an American century because of the rise of U.S. as a global superpower and its influence over international affairs following World War II.

In April of 2014, a little more than 11 months before Rubio would launch, his advisors explained the senator’s approach in interviews with the Washington Examiner.

The goal was to become the first choice of “many” GOP primary voters and the second choice of “even more,” his team explained. “We have gone to great lengths over the past couple of years to avoid at all costs becoming the flavor of the month,” senior strategist Todd Harris told the Examiner for a story that posted on May 1 of that year. “We thought that it was important to take the long view.”

As the 2016 contest unfolded, the senator implemented a strategy that was built around harnessing positive media and momentum that, at just the right time — say, the few weeks leading up to first votes in Iowa — would overwhelm the competition. Hence, an almost maniacal attention to managing expectations in order to avoid peaking too soon and running out of steam, as happened to Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker and retired pediatric neurosurgeon Ben Carson.

It’s unfair to say that Rubio didn’t have a grassroots operation. But his campaign’s theory of the race flowed from its candidate’s unique strengths as a communicator who could connect with a broad audience. The approach stood in stark contrast, for instance, to Cruz.

Cruz periodically loses control of his campaign’s message and narrative, something that didn’t happen to Rubio until the final weeks of his campaign as losses in primaries piled up. But what Cruz did do was create a grassroots juggernaut. This strategy has garnered him more victories over Trump than any other candidate, beginning with the Feb. 1 Iowa caucuses.

And yet for all the Monday-morning quarterbacking directed Rubio’s way, his strategy nearly worked. He charged into New Hampshire on Feb. 2 with the momentum of a frontrunner, despite finishing third in Iowa. Rubio was sitting in second place in New Hampshire, and rising three to five points a day in internal polling, before he ran into New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie in that debate in Manchester.

That one bad moment, just three days before New Hampshire voted, was his first error in nine debates going back to the first faceoff in Cleveland last August. But that was all it took to turn a possible first or second place in New Hampshire into a disappointing fifth behind Trump, Kasich, Cruz and Bush. Not only did that set back Rubio’s plans for snagging an early state victory, it kept Kasich and Bush in the race.

Rubio’s stumble, combined with their continued presence, halted a rush of endorsements and donors that were poised to join senator’s campaign and forced him to fight through a divided field that hurt his cause, in South Carolina and in the states that voted afterward.

“They had the horse but they didn’t get the trip and that’s mostly because of strategy. They got clogged up in a crowded race in New Hampshire with three other candidates fighting for the same space and put themselves in a spot where one bad debate could beat them,” said a Republican strategist who requested anonymity in order to speak candidly.

“They’d planned on South Carolina being their coming out party but it’s a lot easier to win there if you’re building on success. By not playing harder in Iowa they made their South Carolina strategy less likely to work,” this operative added.

A few days before the Palmetto State voted, Gov. Nikki Haley backed Rubio, a major blow to the rest of the field other than Trump, who would win easily.

This helped Rubio recover from the New Hampshire disaster; he finished second, ahead of Cruz, and a lot of the money and endorsements that had held off after the senator’s Granite State stumble started rolling in. But after another second place finish in Nevada a few days later, the Rubio campaign reassessed its strategy with regard to Trump.

Rubio was consistently rated in public polling as the most liked, well thought of candidate in the GOP field. He regularly did better than his competitors in hypothetical matchups with Clinton, the Democratic presidential frontrunner. Rubio often led polls when GOP voters were asked to name their second choice for the nomination. In early March, he was even winning the battle over Cruz among movement conservatives over who should step aside to allow for a cleaner shot at taking down Trump.

But none of this was adding up to victories over Trump. Rubio throughout the campaign had avoided picking a fight with the frontrunner in favor maintaining a positive message focused that was mostly focused on the issues. The exception to that was his willingness to mix it up with Cruz. But after the Nevada caucuses on Feb. 23, Rubio was under pressure to make a play for first place by directly challenging Trump, the candidate in the lead.

The Rubio campaign agreed that the time had come to do so. At first, it worked.

During a debate in Houston on Feb. 25, Rubio caused Trump fits with attacks on his business record and lack of substantive policy proposals. He was declared the winner of the debate and opponents of Trump everywhere cheered him. The next morning, at a packed campaign rally in Dallas, Rubio expanded his attacks on Trump to include the kind of personal insults that the New Yorker had used so effectively to derail others.

It appeared to be working. Television news coverage of Rubio increased, just to see what attacks on Trump he would fire off next; attendance at his campaign rallies reached their highest yet, and the senator came within three percentage points of defeating Trump in Virginia on March 1. Cruz won Texas, Oklahoma and Alaska, garnering more delegates, but Rubio was competitive that night and even finished ahead of Cruz in Georgia.

Two subsequent events appear to have damaged Rubio beyond repair.

The March 3 debate in Detroit was not his finest hour. Although Rubio’s merciless attacks on Trump that night might have actually inflicted lasting political damage on the real estate developer that accrued to the benefit of Cruz and Kasich, the senator’s standing with voters plummeted. They deemed the shots he took to be too personal and insufficiently substantive.

In states where polls had shown him to be competitive, like in Kansas and in Michigan, the bottom dropped out. Rubio was swept in the March 5 Super Saturday contests, and failed to win even one delegate from the four states that voted on March 8. The negative momentum, goaded by nonstop negative press coverage, was too much to overcome.

The Republican strategist said Rubio faced several struggles in this campaign, and that many really had nothing to do with him but can chalked up to bad timing. “Thematically, he has had another struggle that is just a structural problem for our party,” this operative said.

“The voters want a candidate with a sharper edge than Rubio and the donors want a candidate who is more experienced and moderate,” the strategist added. “The thing that made Rubio everyone’s second choice, and the strongest general election candidate, is the same thing that made him the first choice of too few people in the primary. That’s not his fault, it’s just a product of our schism.”