In a sense, human beings are constantly playing games with one another. Whether finding one’s place in the pecking order, testing another’s mettle, angling for scarce resources or more desirable companionship, or striving to predict and influence others’ behavior, many and perhaps most of our species’ interactions can be fruitfully analyzed through the lens of game theory. One particularly chock-full area of recent research involves the technical term “common knowledge,” referring to cases where just about everybody knows that everybody knows a certain thing, and everyone is aware of that, and so on down an infinitude of self-referential rabbit holes that nonetheless remain socially germane.

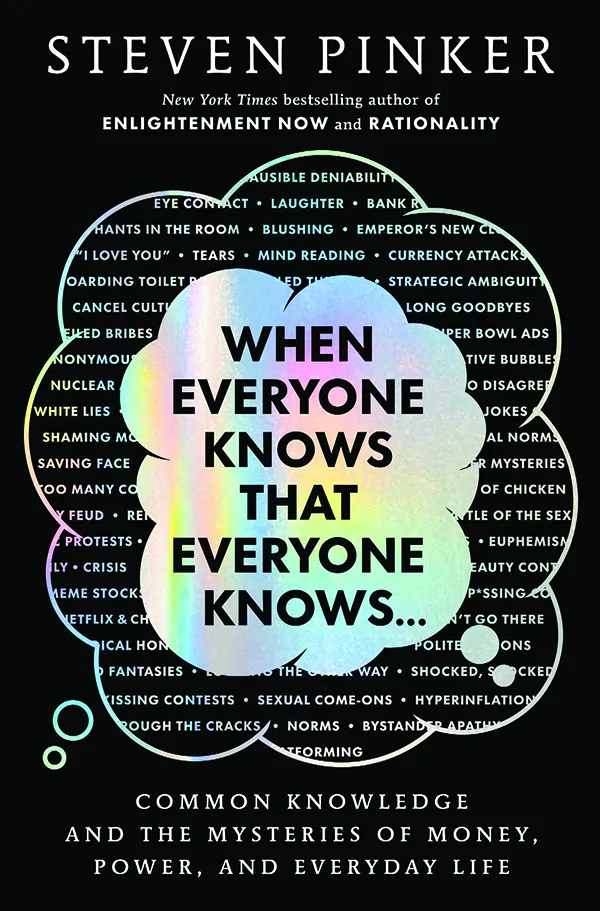

Harvard University cognitive scientist Steven Pinker’s head-spinning new book, When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows . . .: Common Knowledge and the Mysteries of Money, Power, and Everyday Life, intriguingly maps out these recursive complexities of how homo sapiens consistently does its best to figure out what’s what and how to proceed accordingly. “The ultimate subject of my fascination would have to be how people think about what other people think, and how they think about what other people think they think, and how they think about what other people think they think they think,” Pinker writes. “As dizzying as this cogitation may seem, we engage in it every day, at least tacitly.”

Across an array of telling examples and illustrations, ranging from Great Depression-era bank runs to the game show Family Feud to the virtually instantaneous canceling of social media villain Justine Sacco during a single plane ride to the knotty Age of Aquarius poetry of psychiatrist R.D. Laing, Pinker maps out how human beings can’t help but try to suss one another, contextualizing bottomless layers of self-referential knowledge and intentionality, and even often managing to act in concert. As much as “an infinite number of propositions cannot fit into a finite skull,” he concedes, our species maintains an impressive capacity for at very least intuitively keeping track of one another’s respective status and sensibilities.

While officially powerful VIPs, such as CEOs and heads of state, can assert dominance via ostentatious indications of wealth and power, more ordinary people have to walk a tightrope between conveying that they’re no pushovers and yet avoiding the constant risk of being perceived as trying too hard. “They may consciously flaunt the trappings of dominance, like loud motorcycles, muscle cars, or an overbearing demeanor, but that can turn into a social paradox,” Pinker posits. “A self-conscious display of dominance will be seen as its opposite, a sign of weakness: as bluster, bravado, bombast, braggadocio, being a blowhard, or, as they say in Texas, ‘all hat and no cattle.’”

Amid such tireless social showmanship, “What is a friendship, or any other relationship?” he asks. “It’s not as if friends sign a contract. A relationship is a matter of common knowledge. If two people are friends, it means that each one knows that the other one knows that the first one knows that the second one knows … that they are friends.… And because a friendship entails that each of you is there for the other whenever support may be needed, it must be periodically reaffirmed.”

Dating back deep into evolutionary history, long before our complex bureaucratized national and globalized societies, cooperation has proved mutually beneficial more often than not, at least as measured by the health and wealth of history’s victors and survivors. Which is perhaps part of the reason, Pinker speculates, that it’s often socially least disadvantageous for many to save face by way of relatively subtle rhetorical retreats: “When people negotiate in fraught areas of human life, they seldom blurt out their intentions in so many words. They hint, wink, sidestep, shilly-shally, and beat around the bush. They use innuendo, euphemism, and subtext, counting on listeners to catch their drift, connect the dots, and read between the lines.”

“In a nutshell,” Pinker suggests, “Social relationships are coordination games, which we solve with common salience and common knowledge … a social relationship is a long game … for an indefinite number of day-to-day games we might play in the future.” Such resulting hierarchies are structured not only by de facto dominance but by the status derived in part thereof: “If dominance is backstopped up by the implicit threat ‘I could hurt you,’ status is backstopped by the implicit promise ‘I could help you’” in terms of credible leaders earning voluntary deference.

But all of that labyrinthine indirectness takes a ton of time and energy. “Why don’t people just come out and say what they mean?” Pinker asks. “It would be quicker for the speaker, less work for the listener, and freer of the possibility of misunderstanding.” As a cofounder of the Council on Academic Freedom at Harvard in 2023, Pinker has a profound stake in the question: he’s preoccupied with fraught issues of intellectual autonomy and viewpoint diversity that have plunged academia into crisis. The human impulse to censor is well-nigh universal, but so, too, are the benefits of expanding our range of understanding.

“So why don’t we cut the crap?” Pinker wonders. “If common knowledge is necessary for coordination, and coordination is a win-win game, why do we keep so much knowledge private? Why the fig leaves, the white lies, the elephants in the room?”

Simple, he answers: “In reality, calling for complete honesty is the ultimate dishonesty. No one really wants it, sometimes for good reason.” There are hard facts about the world and human social relations that are so inconvenient, painful, or downright shameful that, regardless of their veracity, a lot of human beings simply cannot abide becoming part of common knowledge. “Euphemism, politeness, genteel circumlocution, and other forms of indirect speech make social life possible, but they have a dark side.”

One unavoidable aspect of that dark side in recent years: even serious scholars and scientists trying to address controversial issues responsibly have increasingly become victims of cancel culture mobs. “They were not just criticized, as advocates of any strong position ought to be, but censored, punished, fired, threatened, harassed, demonized, libeled, and in some cases physically assaulted,” Pinker laments. “Worse, for every scholar who is sanctioned, many more self-censor, knowing they could be next.” As many people’s most cherished beliefs emerge not from empirical fact-finding but from moral convictions, troublesome ideas are often renounced and suppressed with fury.

“Norms exist to the extent that everyone knows that everyone knows they exist,” Pinker writes. “A moral norm may be endangered if a threat to it becomes commonly known, and so defenders of the norm feel they must prevent the threat from becoming common knowledge, and if they fail, to punish the threatener as a commonly known example to all.”

For whatever benefits of such social immune response in resisting truly toxic or ungrounded ideas, it has become a mortal threat to the discovery and transmission of knowledge. “The only way that our species has managed to learn anything about the nature of things, and to claw increments of progress out of an indifferent universe, is by a process of conjecture and refutation,” Pinker warns. “Any institution that disables this cycle by repressing disagreement is doomed to chain itself to error … An academic establishment that stifles debate betrays the privileges that the nation grants it and is bound to provide erroneous guidance on vital issues like pandemics, violence, gender, and inequality.”

MAGAZINE: ROCK ‘N’ ROLL’S GREATEST OASIS

And yet that doesn’t mean filters and good manners can or should be dispensed with altogether. Human beings are highly interdependent creatures, and some degree of tact, flattery, and guile is necessary in collective actions ranging from friendships to sports to business to politics; human endeavors tend to require both poetry and prose.

“Authentic human relationships depend on the hypocrisy of keeping many kinds of private and reciprocal knowledge out of common knowledge,” Pinker argues. “The tension between aggressively expanding our knowledge to advance human understanding, and hypocritically keeping some knowledge private to preserve human harmony, is inherent to our condition.” Everyone knows that, or probably should.

Jesse Adams is the writer and consultant behind The Ivy Exile on Substack.