Twelve years ago, when the National Assessment of Educational Progress reading scores came out, the Magnolia State surprised no one by landing 49th out of 50 spots. Mississippi is a state with its share of major struggles. Located in a region of the country known as the Deep South, it stands out for some uncomfortable reasons. It ranks as one of the most poverty-stricken states in the nation. In terms of health system performance, Mississippi scored dead last on the Commonwealth Fund’s 2025 scorecard. And even if they’re not from the area, most Americans have at least a small understanding of the tenuous race relations that have plagued the state since its early-19th-century establishment.

For these and other reasons, Mississippi and its people must apply hard work toward vast improvement across the board, and education is no exception.

More than a decade after the abysmal NAEP ranking, Mississippi is now shocking everyone, including those in the state, with an unprecedented turnaround in reading and even math scores. According to the Urban Institute’s 2024 figures, adjusted for demographics, Mississippi now ranks first in reading for fourth grade and fourth in reading for eighth grade. And in math, Mississippi ranks first for both fourth and eighth grade. The twofold question on everyone’s mind is: How did Mississippi get here, and how can other states copy the success? As scores for reading plummet in other states, the Magnolia State is now, rather unexpectedly, a role model for educational improvement.

What is now dubbed the “Mississippi Miracle” began in 2013 under then-Gov. Phil Bryant. During the legislative session, the Literacy-Based Promotion Act was passed. It was implemented during the 2014-15 school year and amended in 2016. According to the Mississippi Department of Education website, the LBPA “places an emphasis on grade-level reading skills, particularly as students’ progress through grades K-3. Beginning in the 2014-15 school year, a student scoring at the lowest achievement level in reading on the established state-wide assessment for 3rd grade will not be promoted to 4th grade unless the student qualifies for a good cause exemption.” The four key components of the LBPA are providing teachers and school districts with the appropriate resources and sufficient training, early identification of students who struggle with reading through proper screening, the creation of an individual reading plan for those identified as struggling, including specialized instruction, and requiring that third grade students pass a state reading test, known as the gate test, to move on to fourth grade. And if third grade students fail the test and are held back, they won’t receive a repeat of the previous year but will instead receive support tailored to their individual needs in order to ensure a final, successful outcome.

Without a doubt, the most controversial aspect of the LBPA was and still is retention for third graders who fail the end-of-the-year reading test. In 2015, the Hechinger Report, a site that covers, among other things, innovation in education, published an article titled “As Mississippi delivers bad news to 5,600 third graders, stressed-out parents say there must be a better way.” The piece delves into how exasperated parents feel as their nervous third graders prepare for the gate test. It also deals with the aftermath for parents whose children were told they’d have to repeat third grade. It’s not an easy situation. Holding back students for any reason is never a pleasant experience for anyone involved, including educators and parents. But both legislators and Bryant felt especially strongly about this major element of the LBPA. Bryant struggled with dyslexia as a child. School and especially reading did not come easily for him. Bryant had to repeat third grade. In 2012, Bryant signed a bill that requires dyslexia screening for kindergarten and first grade students so early intervention can take place. At the time, he said, “It can be treated. You can overcome this. And one of my great joys and passions today is reading.”

According to Anne Wicks of the George W. Bush Institute, the end-of-year gate test and retention features of the LBPA were a tough sell: “When it was first implemented, many parents fought against the so-called third grade gate, arguing that retention would hurt their kids’ mental health more than promotion would help their education. But Bryant and state leaders held firm, convinced that their new approach would benefit students.” More than a decade after enactment, the strict demands of the LBPA are bearing excellent fruit that serve as a model for the rest of the nation. But that doesn’t mean the real-life experiences of the students and families are easy.

The Mississippi Miracle is personal to me and my family because we live in the state. We are transplants from the Midwest because my husband’s career led us here more than a decade ago. Now, we are parents of two young sons. Like most parents, education is important to us. But our journey has been different from the majority of families. Our oldest son, who is 9, has a speech delay. We noticed it early on, and he began to receive speech therapy and early intervention from the state when he was 2. This was all done with a future in mind that included attending public school and learning alongside his peers in a regular classroom setting. But how it would look for him when he entered school was a mystery to us. From the start of his schooling career, he has had an individualized education plan. IEPs are not unique to Mississippi — they are used nationwide in the public school system. They are for children who need some form of special education help, whatever that may be. In our son’s case, it is therapy with a speech-language pathologist to aid him in his educational journey. When he entered second grade, we were told that at the end of third grade, he would have to take the gate test to even pass to fourth grade. He did not qualify for a good cause exemption. All this combined caused more than a small amount of alarm. If some children without IEPs fail the test, how would our son, with a speech IEP whose main struggle is reading comprehension, fare as an 8-year-old when faced with make-or-break testing? Needless to say, both the preparation and the worry became almost equally paramount in our lives.

At the start of third grade, his teachers and speech therapist placed an emphasis on the end-of-year testing. But this wasn’t just a discussion about a looming date on the April calendar. Instead, it was a continual focus on reading and comprehension instruction, specialized for our son as needed, encouraging him to read at home, and unhindered communication between us and his teaching and therapy team. Our son had tons of support as he went through his year. Even with an IEP, he did not, and was not allowed to, receive help during his gate test. We, as a collective group of teammates, were thrilled when he passed the state gate test on the first try. It was a joy to know all that work led to a major win. He is now in fourth grade, and I’m happy to report he is not only excelling in reading and math, but has markedly improved year over year in a way that we had only dreamed of at the beginning of third grade. There are sure to be many factors for that, but a major one is the support and instruction he received through a sometimes strenuous third grade year.

Our experience as parents is just one of many in the state. There are certainly those who aren’t fond of the strict requirements of the LBPA. And it’s important to remember that it is indeed tough for those children who must repeat the grade. It’s imperative that special support be given to students who are faced with retention. They should not be shuffled through in any way whatsoever.

Is a third grade pass or fail test worth it? Based on the soaring reading scores for fourth graders in the state of Mississippi, it seems the answer is a resounding yes. Other states should waste no time in trying to replicate what is clearly a winning formula.

The idea of making big, sweeping changes in education seems next to impossible, given all the factors in play. Far beyond the legislative changes and money allocation, there must be a concerted effort across the board by not just administrators and teachers, but also students and parents. It is truly a team effort. But given the impact on students’ present and future, it is more than worth it. Other states looking to follow Mississippi’s lead should know the changes did not happen overnight. As Tenette Smith with the Mississippi Department of Education said, “Some people call [improvements in reading proficiency] the ‘Mississippi Miracle.’ It has nothing to do with a miracle.”

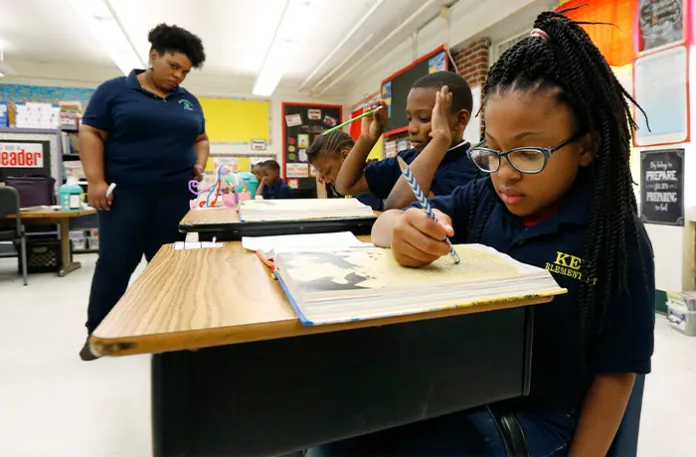

The total cost of the yearly investment in the state’s literacy program stands at $15 million, up from $9.5 million that was allocated in its first year. As reported by Education Week, 60% of that money “goes to coaching and intervention services staff.” The literacy coaches hired by the state must meet tough requirements and be proficient in what is called “evidence-based reading.” Lucindy Cunningham, a teacher in Greenville, Mississippi, sees these coaches as a major asset: “Prior to the 2013 literacy act, she wasn’t expected to teach in alignment with the evidence on reading. Having a literacy coach made that shift easier, she explained. She ticks off some of the ways these coaches have supported her: showing her how to set up literacy centers in her classroom that focus on the core components of reading; identifying useful resources, such as those from the Florida Center for Reading Research; explaining how to interpret data from reading assessments and apply it to improve reading achievement; and supporting effective ways of teaching writing.” Now, regular teachers can meet the guidelines and teach evidence-based reading as they’re well-supported by coaches who aren’t there to compete but to aid them as well as the students. As Wicks discusses in her essay on Mississippi’s success, the “balanced literacy” approach of teaching was the standard for decades before the LBPA was enacted. And even now, many school districts around the nation still use it. What Mississippi did was instead switch to the “science of reading” approach. Literacy coaches sent to school districts, especially the ones struggling the most, ensured the science of reading was taught in the classrooms. This bolstered student learning. Wicks praises this as Mississippi “embedding professional development in the classroom.”

Teachers themselves also receive continuing education. As reported by Education Week, “Another component of the state’s literacy act was to overhaul its professional development related to reading instruction. The state now provides to all K-3 general ed teachers and K-8 special education teachers a yearlong, master’s level professional development course grounded in the science of reading.” For teachers who have been used to the “balanced literacy” approach, the science-based focus is new. But one only needs to look at how the professional development translated to classroom instruction and, eventually, higher reading scores. Support for teachers by way of instructing them and providing literacy coaches has paid off.

Another helpful tool has been the Literacy-Based Promotion Act Implementation Guide. The Mississippi Department of Education prepared this to clearly define what the law requires and the responsibilities of all the players involved, at every level, from the state to the individual classroom teacher.

The Mississippi Miracle is a multipronged campaign to increase literacy across the state that has only been achieved through hard work and dedication. And it’s been a success in a state with much less to spend on education and more poverty than most other states in the union. As has been noted, it is possible for other states to copy the success. But whether states want to give it their collective all is another story entirely: “More than 20 states now have a law or policy in place designed to improve reading outcomes, and others are debating creating the same. Some states have banned poor practices or required the use of high-quality curricula, but they haven’t included the kind of robust commitment to educator capacity that Mississippi did with its investments in coaching and training. Other states have considered adopting Mississippi’s policy on third grade retention but have not established that the repeated year will be structured in a way that ensures kids get what they need.”

THE ENEMY OF YOUR ENEMY IS NOT YOUR FRIEND

Because this Deep South literacy “miracle” is actually no miracle, it requires that legislative changes then become real-life commitments at the state and local levels, among administrators, teachers, students, and parents. At times, it requires some tough love and temporary but severe disappointment in the form of retention. However, the goal of helping children succeed is worth it for the short-term and even long-term benefits. My own family has seen it in our son’s life as he not only passed the gate test but has grown leaps and bounds in the area of reading comprehension. It is aiding him to this day as he more confidently approaches reading at both school and home.

Fifteen years ago, no one could have predicted that the Magnolia State would be a leader in education. But it is. And the gains are not just in better scores now, but in brighter futures for children and their families, and a stronger state as a whole. Will other states follow suit? As Mississippi has demonstrated with its own success, it really is all up to them.

Kimberly Ross (@SouthernKeeks) is a contributor to the Washington Examiner’s Beltway Confidential blog and a contributor to the Magnolia Tribune.