For all the puns, the globetrotting, the exhuming of forgotten American sins and the pomo blenderization of science, poetry, journalism and junk culture, Thomas Pynchon’s now 60-plus-year oeuvre is largely obsessed with one two-headed monster of a question: Where does violence come from, and what does it look like when it encroaches on our allegedly otherwise peaceful world?

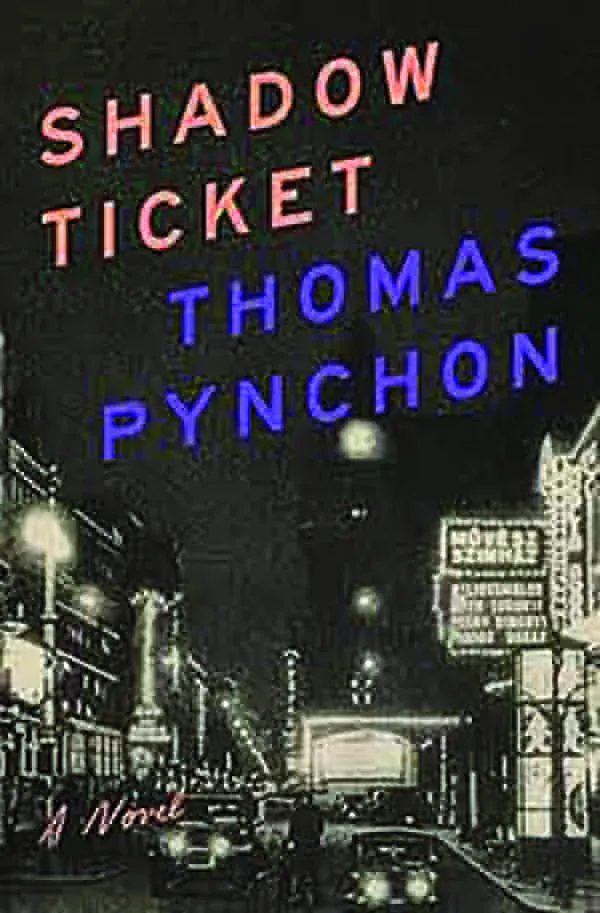

In Shadow Ticket, his first novel in 12 years, the 88-year-old master explores the explicitly political dimension of this question. Given the inexorable temptation toward polemic, miscalculation, and outright crankdom on this subject for any novelist, even one of the greats, this is a perilous venture. Fortunately for all literate people, he has succeeded, delivering an unlikely late-career masterpiece in the shape of an at first glance slight, 294-page detective novel full of cheese puns.

Shadow Ticket, like generational peer Philip Roth’s own as-the-shot-clock-runs-down masterpiece The Plot Against America, returns to the period and preoccupations of Pynchon’s youth. It’s 1932 at the brutal dawn of the Great Depression and amid a nihilistic interwar cultural bacchanal. Prohibition reigns, but everyone knows it’s a sham and the federal “prohi” crusaders are on the take. Childhood, romance, and neighborhood social bonds are mediated by mob cliches. Midwestern business machers whisper in fear of the Bolshevik revolution coming next to their shores in the form of Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Crouching and scratching his head, ape-like, at the center of this brewing maelstrom is Hicks McTaggart — a middling dick in the service of “Unamalgamated Ops,” a corporatized rent-a-cop service that caters to the booming business in infidelity among the country’s young and precarious middle class. McTaggart operates out of Milwaukee, where white ethnic tensions are very much alive in the form of the Italian-controlled “Third Ward” from which all anarchist violence is assumed to flow and the beer halls and bowling alleys where newsreels depicting the rise of a “certain German Political Celebrity” meet a warmer reception than they otherwise might.

Through a series of Pynchon’s typically labyrinthine and obscurant plot contrivances, McTaggart is, under duress, given the book’s titular “shadow ticket,” a contract to track down the disappeared heiress to the country’s preeminent cheese baron, Bruno Airmont. (For fans of Pynchon’s famously slapstick-poetic naming conventions, this book does not disappoint: There’s “Thessalie Wayward,” a psychic secretary; “Zoltan von Kiss,” a questionably supernatural Hungarian con artist; “Squeezita Thickly,” a nauseating, parodic hallucination of Shirley Temple.)

Shortly into his investigation, McTaggart discovers that the Old World is very much alive around him. A rogue Austro-Hungarian U-boat, having roamed the seas unaccounted since the end of the Great War, surfaces from Lake Michigan and absconds with a neighborhood Milwaukee tough (“Stuffy Keegan,” another perfect name). Sicilians — real ones, not the movie kind — haunt McTaggart’s investigations, not to mention what counts as his love life. And a new, eerily clean bowling alley pops up on the fringes of the city, where “a dance floor full of Lindy-hopping youth” gets their kicks to a swingtime rendition of the Horst Wessel Song.

Inevitably, McTaggart is drawn back to Europe, slipped a mickey, and unceremoniously dumped aboard an ocean liner bound for Tangier and ports of call beyond. Here, too, the past won’t let go: “Passageways long after hours clamor with what sounds like an immense unsleeping crowd,” Pynchon narrates, one character elaborating that the liner was “converted during the War to a hospital ship … Still populated by casualties physical and psychical and those in whose care they were conveyed … unquiet stowaways with broken odds and ends of unfinished business from the War, common to all being a hope no longer quite sure and certain that injustices would be addressed and all come right in the end.”

Slipping between pitch-perfect hard-boiled patter, situational comedy, and these flights of existential pathos, Shadow Ticket delivers a familiar punch for Pynchon’s faithful. Where it differs, and shines, is in its economy and clarity. This book is the work of a writer who hasn’t grown woollier with age, but more refined and urgent, distilled to exactly what this story requires but retaining his signature gnomic charm. A sneering FBI agent, alluding to McTaggart of “the future U.S. we in the Bureau expect to see before long,” sends him away with the customary door prize for new immigrants at Ellis Island, a Jell-O mold of the Statue of Liberty. “Where do you start eating it? The head? The torch?”

On the trail of the cheese heiress, the gumshoe eventually lands in Budapest, metonymic for Europe’s rupture and bitterness in the wake of the Treaty of Trianon that truncated Hungary’s borders and set off a century of ethnic irredentism. Here, fascism isn’t just a pop culture specter on a newsreel or phonograph. It’s the “Vladboys,” a psychotic motorcycle gang with delusions of petty grandeur under a trans-European Reich, or Heino Zäpfchen, a “Judenjäger” who hunts down the detective story’s driving MacGuffin in the form of a dashing Jewish clarinet player.

“Heino gets to make the final call,” a wiseacre journalist expounds to McTaggart by way of exposition. “If he says they’re a Jew, whatever they were when he made the collar, by the time he brings them in, they’re a Jew.”

The brutality meted out during this story, like that in Pynchon’s bibliography going back to the hallucinatory sadism of his besieged, colonial African manor in 1963’s V., is libidinal. Ideology — whether the collared party is, in fact, a Jew — is immaterial. What matters is the kill, the moment of violence, the sexual release toward which Pynchon’s more impressionistic dark passages always seem to be sliding. A neutered husband finds himself on the other end of his wife’s pistol. A father and daughter share a decidedly unwholesome moment on the dancefloor. Russian agents guard a dark secret “beyond trivialities of known politics or history … so grave, so countersacramental, that more than one government will go to any lengths to obtain and with luck to suppress it.”

Critics have curiously dismissed Shadow Ticket as a minor work, citing its lack of cathartic resolution and heavy reliance on schtick-y humor, as if these weren’t the bedrock of this American master’s life’s work. In fact, the book might be too clean a synthesis of his themes and obsessions to satisfy his own reputation for sprawl, ambition, and authority. It’s funny, it moves, and most importantly, it leaves bare its author’s intentions, for once and possibly for all.

As civilization’s horizon dims at the eastern edge of Europe, soon to come for the rest of it, McTaggart and the heiress he’s pursued are too busy conforming to dime-store noir scripts to say the words that Pynchon puts in their mouths: “What one of them should have been saying was ‘We’re in the last minutes of a break that will seem so wonderful and peaceable and carefree. If anybody’s around to remember. Still trying to keep on with it before it gets dark … Those you could have saved, could’ve shifted at least somehow onto a safer stretch of track, are one by one robbed, beaten, killed, seized and taken away into the nameless, the unrecoverable. Until one night, too late, you wake into an understanding of what you should have been doing with your life all along.’”

At the end of the book, history literally disappears. Roosevelt is overthrown by General MacArthur shortly after his election, leading to the long-dreaded capital-R Red Revolution in America. The novel’s cast of characters realizes that maybe they’re stuck in the Old World for good, although an unexpectedly stirring final epistolary chapter suggests — surprise — America’s renewal in the West, a theme explored contiguously to this novel’s timeline in 1990s Vineland.

In a 1993 New York Times essay about sloth, Pynchon wrote that “In this century we have come to think of Sloth as primarily political, a failure of public will allowing the introduction of evil policies and the rise of evil regimes, the worldwide fascist ascendancy of the 1920’s and 30’s being perhaps Sloth’s finest hour.” He nails the vice to the wall as “a deliberate turning against faith in anything because of the inconvenience faith presents to the pursuit of quotidian lusts, angers and the rest.”

ABANDON ALL HOPE, YE WHO ENTER HERE

Despite being on its surface a political novel about borders, parties, and ethnicities, Shadow Ticket is really a case study in the moral laxity and cynicism that allows society’s malcontents to do violence in their name. The musical genre, the language, the slang might change, but the gangsterism and the screaming id remain the same. “Better if somebody tells you now,” one grizzled old P.I. tells McTaggart’s protégé in the novel’s closing pages. “Innocent and not guilty ain’t always the same.”

In other words, the letter of the law and one’s immortal soul might forever remain at odds, a principle that in true noir fashion more often benefits Pynchon’s villains than his heroes. And yet still, the latter wander and wisecrack, rarely so stirringly as in Shadow Ticket, both an essential kiss off to the 20th century and testament to a life’s work in tragicomic humanism.

Derek Robertson is a writer based in Brooklyn.