As the federal government shutdown enters its fourth week, it is already the second-longest on record. A weary American public should start thinking not just about how to stop this shutdown but how to prevent these embarrassing episodes in the future.

Shutdowns have not always been part of the political landscape. Although our country has had 22 of them, they are a relatively recent phenomenon. The first shutdown took place only about half a century ago, under President Gerald Ford. Ford vetoed a spending bill that had been passed by the so-called “Watergate Baby” Congress, elected after President Richard Nixon’s resignation in 1974. An emboldened Democratic Congress flexed its muscles against a weakened presidency, overrode Ford’s veto, and ended the impasse.

Three factors have contributed to the rise of shutdowns in the ensuing years. First was the 1974 Budget and Impoundment Control Act, which increased the power but not the responsibility of Congress in the budget process. Second was an interpretation of the Antideficiency Act by Jimmy Carter Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti that limited the ability of agencies to spend unappropriated expenditures. This change meant that if the previous appropriations bills expired without new appropriations being approved, the agencies could no longer spend money in expectation of those approvals, so the government would “shut down.”

A third factor was the election of a Republican Congress in 1994 after decades of Democratic rule. With control of Congress now regularly contested, spending disagreements gained more political import. A legislator consigned to the minority for a long period might be more inclined to compromise than a legislator expecting to be back in the majority after the next election. As a result, spending fights have become more bitter, and legislators more obstinate, in this era in which control of Congress is more fluid.

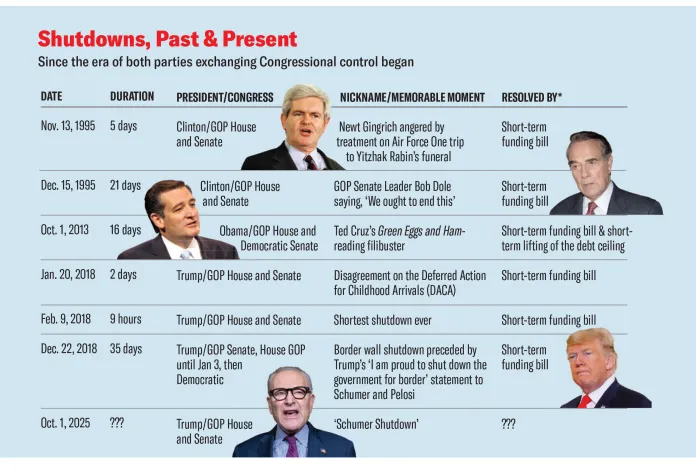

A review of subsequent shutdowns reveals some predictable patterns. According to the Congressional Research Service, shutdowns usually — 15 times — end quickly with a short-term funding extension. In addition, shutdowns rarely end with major legislative changes. They can highlight issues, but they have not substantively changed policy in any of the post-1994 shutdowns.

A recurring shutdown issue is the question of blame. For the most part, shutdown blame is typically not based on who has the White House or which side starts it but on something else entirely: When Republicans start them, the media blame the Republicans, and when Democrats start them, the media blame … the Republicans. According to a 2019 CNN analysis of seven shutdowns on which there was public polling, Republicans have, in all but one instance, taken more of the blame in the dispute. This pattern suggests that the liberal-leaning media have more sway over how the public views the shutdown than the relative merits of the two sides’ arguments.

This does not mean that behavior is not a factor. In the Bill Clinton–Newt Gingrich shutdown of 1996, Gingrich’s snit about being snubbed on exiting the plane headed to Yitzhak Rabin’s funeral contributed to his refusal to negotiate, and to the Republicans losing the public relations battle in the ensuing shutdown. Gingrich himself recognized his mistake, joking at the 1998 Gridiron dinner that he “mishandled the Air Force One episode. Maybe shutting down the government was a little overkill. I didn’t realize the correct answer until I saw the recent Harrison Ford movie. Rather than telling the press my feelings were hurt and closing down the government, I should have that night simply taken over the plane.” While Clinton is now seen to have won that shutdown, it’s worth noting that he was uncertain about the outcome going into the dispute. As Clinton wrote in his memoir My Life, “With the government shutdown looming, it had been far from clear that I would prevail or that the American people would support my stance against the Republicans.”

Even though Republicans usually get tagged with the blame, that blame does not necessarily have a lasting effect. Republicans lost the PR war in the 2013 Obamacare shutdown, in which Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) worked with House Republicans to create a showdown to try to end the Affordable Care Act. Cruz was blistered by the late-night comedians for his effort: Jon Stewart mocked Cruz’s filibuster reading of Green Eggs and Ham, saying, “To express your opposition to Obamacare, you go with a book about a stubborn jerk who decides he hates something before he’s tried it.” And Stephen Colbert created a Green Eggs and Ham-inspired rhyme to tout Cruz’s political opponent: “I will not eat them in a box. I will not eat them with a fox. I will not eat them with a fork. You should vote for Beto O’Rourke.” As Cruz likes to point out, though, Republicans did not suffer as a result, winning the next two elections, the 2014 congressional midterm elections and the 2016 presidential race. This recognition that they can survive the rigged blame game makes Republicans less likely to yield.

Democrats may not admit that the media prove decisive in apportioning blame during shutdowns, so they have their own mythology of why they come out on top. For them, the shutdown was the key to Clinton’s political comeback in the 1990s, when GOP Sen. Bob Dole eventually yielded on the Senate floor, saying, “We ought to end this. … I mean, it’s gotten to the point where it’s a little ridiculous as far as this senator is concerned.” Nearly two decades later, Barack Obama and his team studied Clinton’s successful 1995 shutdown playbook in preparation for the 2013 episode. In Democrats’ minds, they have nothing to fear in a shutdown. In fact, they can be confident that it is a game-changer, even when, in this case, it is the Republicans decrying a “Schumer Shutdown.”

Politics aside, shutdowns are reflective of a larger structural budgetary problem. Every shutdown in history has taken place since the passage of the 1974 Budget and Impoundment Control Act. As a result of that legislation, Congress now creates a largely aspirational budget in the form of a budget resolution, while the actual spending decisions are made by the appropriations committees. This flawed approach has led to ever-higher levels of spending and debt. Since the act started, annual federal spending has gone from $269.4 billion (approximately $1.8 trillion today), which was less than 20% of GDP, to nearly $6.8 trillion, representing about 24% of GDP. With all this spending comes great heaps of debt. In this period, the debt has gone from about $475 billion to $37 trillion, with the debt-to-GDP ratio growing from 31% to about 124%.

A rational review of this history should lead to the conclusion that frequent shutdowns demonstrate the desperate need for reforms that put teeth into the budget process. Congress should be required to meet its budget deadlines, with automatic continuing resolutions going into effect if they do not. Such a reform, which was championed by former congressman Chris Cox in the 1990s, would force Congress to make real spending choices. It had over 200 sponsors, from both parties. As Cox, for whom I once worked, observed, process reform could give politicians cover for tough decisions by allowing them to say that “the process made me do it.”

Cox’s proposal did not become law in the 1990s, but it’s important to recall that the debt was much more manageable then. As Cox recently told me, there is now far greater potential for his reforms because of the deleterious impact of the ever-growing debt. According to Cox, “Exhibit A in recent weeks is the record price for gold, and the fantastic run-up in the price over the last year.” Cox noted that the increases are “driven in no substantial part by central banks moving out of Treasurys and into gold.” Such a development has not only domestic but also geopolitical implications. As Cox put it, “Not only have Russia and China long been conniving to dethrone the U.S. dollar as the global reserve currency, but now many other nations are (for purely safety reasons) abetting the cause by building up their gold stocks and becoming less reliant on the U.S. dollar.”

THE PRESIDENTS AND IRAN, A HISTORY

Despite the need for this reform, both parties need to recognize that there is a political groundswell for change. This will take real work. As Cox observed, “The vast majority of the American people must first be convinced that this connection exists before there will be pressure on Congress to deal with the problem.” To make this happen, he said, “people within and without the halls of government need to be making the case that inflation is an evil, regressive tax that hurts everyone (though surely seniors and the poor hardest) and that profligate policies in Washington are at the root of it all.”

It’s too soon to see how this particular shutdown will end, although history suggests that a short-term funding extension is once again the most likely outcome. Regardless of what happens this time around, the frequency of these shutdowns, coupled with our worrisome long-term debt and spending trajectories, shows that the results of any one shutdown are far less urgent than the need to reform the system that brings them about.

Tevi Troy is a senior fellow at the Ronald Reagan Institute and a former senior White House aide. He is the author of five books on the presidency, including, most recently, The Power and the Money: The Epic Clashes Between Commanders in Chief and Titans of Industry.