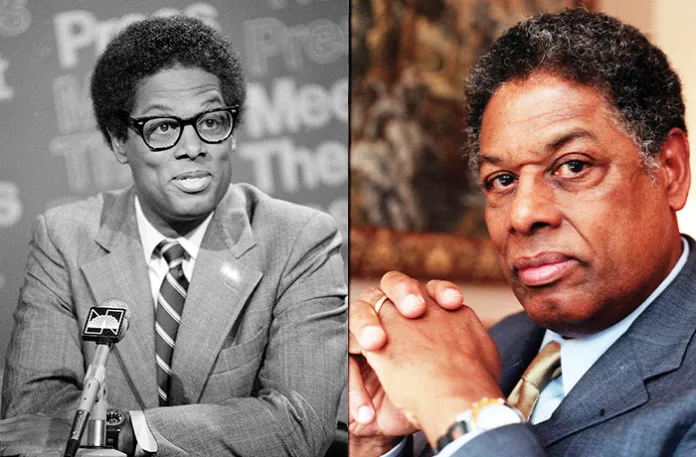

The economist and public intellectual Thomas Sowell turned 95 years old in June. Outside of national politicians and high-profile celebrities, few public figures are as well-known inside the halls of academia as they are outside of them. It is rare for an academic to achieve this status, but considering that Thomas Sowell is exceptional in so many ways, it is almost tautological to describe him as such. He is black, right of center, and despite a halting path through the educational system, something he has commented on over the years, he earned a doctorate in economics from the University of Chicago and has taught at some of the most elite universities and colleges in America.

Whereas academics and intellectuals tend to be a timid bunch, going along to get along, Sowell has consistently and confidently gone his own way. A telling conversation he recounted in his 2000 memoir, A Personal Odyssey, perfectly captures the defining characteristic of his writings and public appearances: his intellectual independence. At Harvard University, after deciding to write his senior honors thesis on Karl Marx, having spent many years reading Marx on his own, Sowell was told by his thesis adviser, Arthur Smithies, that he would not be much of a resource because his knowledge of Marx was limited. Sowell responded, leading to the following exchange:

“That’s all right,” I said. “I plan to do it all by myself anyway.”

“I know,” he said, “but usually the student needs some guidance and suggestions about organizing the work, as well as some helpful readings on the subject.”

“My plan is to ignore all interpreters of Marx, read right through the three volumes of Capital, and make up my own mind,” I said.

“Well, it so happens that Paul Sweezy, the leading authority on Marxian economics, is right here in Cambridge, and I could introduce you to him.”

“That won’t be necessary,” I said.

Sowell went on to explain that he was adamantly opposed to having “anything I did attributed to ideas picked up from Paul Sweezy or anyone else.” Parts of his honors thesis on Marx were eventually published in academic journals.

Perhaps it was his early adoption by extended family, or the experience of growing up in poverty in the segregated South before moving to Harlem, whatever the cause, Sowell’s indifference toward intellectual fads and jargon lends credibility and depth to his body of work.

Having written nearly 45 books, countless articles, including his syndicated column, Sowell has formed an intellectual legacy that is both comprehensive and influential. Among contemporary black conservatives, “If you ask, ‘Who has been the most formative figure in your intellectual development?’ nine times out of 10, the answer will be Thomas Sowell.” In Michael Pack and Mark Paoletta’s book, Created Equal, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas speaks glowingly of Sowell’s influence on his life. “I sought out [Sowell’s book Race and Economics], read it voraciously, and this really had a tremendous impact on my life. Thomas Sowell is incapable of deception, and he is absolutely brilliant. His work is insightful.”

I, too, have been positively affected by Sowell’s writings. As a freshman in college, I was introduced to his work by my dormitory’s resident assistant, who was an economics major. During one of our many conversations, I apparently expressed a Sowell-sounding line of thought on a topic that the RA found so unusual coming from a black student that he quipped, “You’re a fan of Thomas Sowell, too, I see.” I had no idea who Sowell was, but I quickly learned. As a freshman, I was not yet a sophisticated reader of Sowell, but, at the time, I read enough to appreciate that Sowell was completely opposed to the view that black people were doomed to be perpetual victims of America’s racist past.

For the most part, Sowell’s oeuvre revolves around three themes: knowledge, culture, and race. The methodological approach Sowell seems to favor when discussing many of these themes is a version of what can be characterized as empirical analysis. The approach relies on observation, experience, and analysis. In his book, On Classical Economics, he defines the method of empirical analysis favored by classical economists such as Simonde de Sismondi, John Stuart Mill, and Karl Marx, in two ways:

“The issue of analytical generality versus empirical generality was part of an even more basic issue – whether economic principles should be founded on abstract assumptions or factual premises. Those who rejected the abstract deductive approach often pointed to the complexities of the real world as a reason for preferring empiricism. John Stuart Mill saw this as a false dichotomy. Both the ‘theorists’ and the empirical or ‘practical’ men used systemic reasoning, starting from given assumptions, and both derived those assumptions from something in the real world. The only meaningful question, then, was the particular manner in which the initial premises were derived from reality.”

Sowell’s work appears to endorse the version of empirical analysis favored by “practical” men. That is, his approach favors “direct induction from particular cases to a general conclusion.” In Sowell’s writings, experience consists of a collection of particular actions or facts, which are distilled into a kind of collective wisdom and valued for their practical utility. Although experience tends to have a practicality to it, the principles derived from experience give knowledge inductively in the sense that the universal is implicitly within it. Sowell seems to regard knowledge or understanding as a matter of comprehensive explanation rather than certainty. In other words, explaining observable social phenomena by identifying their causes reflects a deep, systemic understanding. We see this to great effect, for example, in Sowell’s early studies on the history of black education. In his collection of essays, Education: Assumptions versus History: Collected Papers (1986), data and Sowell’s own experience are woven together in a compelling and persuasive way to show that academic achievement among black students, historically, has been achieved in all-black schools. The story that Sowell recounts of the all-black Paul Laurence Dunbar High School in Washington, D.C., has been especially insightful in explaining the factors that have harmed and helped black education in America.

Sowell’s empirical, experience-based method forms the foundation of his analysis in Knowledge and Decisions, A Conflict of Visions, and The Vision of the Anointed. Of the three books, Sowell’s Hayek-inspired Knowledge and Decisions is the most philosophically robust — it won the 1980 Law and Economics Center Prize. The book explores the function of knowledge and how it is conveyed and utilized in society through feedback mechanisms. Sowell illustrates the role of feedback mechanisms in various settings such as the economy, morality, and law. These mechanisms allow individuals and institutions to alter their behavior based on real-world outcomes. Ignoring the opportunity to adjust behavior based on feedback, whether at the individual or institutional level, often leads to negative consequences.

As Sowell explains:

“Insulation from feedback takes many forms, not the least of which is duplicity. Administrative agencies have turned the Civil Rights Act’s equal treatment provisions into preferential treatment practices. … A ‘results’-oriented Supreme Court creates constitutional ‘interpretations’ that horrify even those who agree with the social policy announced. Quite aside from the moral issues, doctrines which cannot be openly argued – quotas, judicial policy making, nonenforcement of criminal laws – cannot be subject to effective scrutiny.”

The effectiveness of feedback mechanisms lies in their satisficing role. In the context of decision-making, satisficing aims to meet criteria for adequacy rather than to identify an optimal solution. A satisficing strategy assumes that optimal decisions, behaviors, arguments, and explanations are impossible to achieve in a given context due to the elusiveness of complete or definitive knowledge at any given time. According to Sowell, feedback mechanisms harness and communicate local, fragmented knowledge through a continuous, albeit imperfect, process.

The topic of cultural capital and its diffusion has figured prominently in several of Sowell’s books. In Race and Culture, Conquests and Cultures, Knowledge and Decisions, and Wealth, Poverty and Politics, he elaborates on the concept of cultural diffusion as it applies to various ethnic groups. He points out, for example, that in places as distinct as Australia, Russia, France, and England, Germans have excelled at building pianos. They were the first to pioneer advances in optical instruments and cameras. They also excelled in military skills in countries around the world. The Chinese, Jews, and Lebanese, despite having been discriminated against, thrived economically wherever they migrated due to their cultural capital. Sowell’s discussion of the Germans and other ethnic groups underscores his argument that more than skills are involved in differentiating these various ethnic groups. Behind the skills are cultural values that make the acquisition of new skills a priority and values that make the shedding of obsolete skills imperative. The argument is insightful insofar as it shows that cultural differences are not random or even:

“Germans are just one of the groups who have taken their own particular culture with them when they immigrated to other societies, so that the general environments of those various other societies were not the controlling factor in these groups’ economic or other outcomes in those societies. … To account for radical differences in income and wealth among groups living in the same society, environment can be defined as what is going on around a group, while culture means what is going on within each group.”

Equal outcome advocates have completely ignored Sowell’s point here. It is simply not the case that if it were not for discrimination, the achievements and outcomes of various groups would be even or random. An ethnic group’s culture has a disparate impact on its achievements and economic outcomes all of its own.

On the fraught topic of race, some of Sowell’s most trenchant analysis can be found in many of his books, such as Ethnic America, Black Rednecks and White Liberals, Knowledge and Decisions, and Wealth, Poverty and Politics. In each of these books, Sowell brings to bear on the topic of black American culture many valuable insights and hard truths. In Ethnic America, Sowell does a magisterial job of documenting the history and evolution of various ethnic groups such as the Chinese, Japanese, Puerto Ricans, Jews, Germans, Irish, Italians, and black Americans. What sets the book apart — it was published in 1981 — is the fact that black people are not seen as exceptional to the American story of generational upward mobility. Sowell does not deny the origin story of how black people arrived on the shores of America — rather, he highlights how the grit and ingenuity of black people, in combination with the exceptionalism of America itself, have contributed to their steady advancement:

“The tragic history of slavery, Jim Crow laws, and lynchings against blacks is all too familiar. Yet what is peculiar about the United States is not that these intergroup animosities have existed here – as they have existed for thousands of years elsewhere – but that their intensity has lessened and in some respects disappeared.”

Which is to say, the majority of Americans, both black and white, do not see black Americans as exceptional for having had ancestors who were enslaved. That is not to say a majority of Americans are indifferent toward our racial past. Quite the opposite: It is to say that black Americans as a group have done an astonishing job within the circumstances in which they initially found themselves, but so have many other ethnic groups.

Sowell sums up the issue succinctly by emphasizing that it is cultural traits that account for differences among ethnic groups and that culture is intangible and portable. Culture includes not only customs, values, and attitudes, but also skills and talents that more directly affect economic outcomes, and which economists call human capital:

“But history shows new skills being rather readily acquired in a few years, as compared to the generations – or centuries – required for attitude changes. Groups today plagued by absenteeism, tardiness, and a need for constant supervision at work or in school are typically descendants of people with the same habits a century or more ago. The cultural inheritance can be more important than biological inheritance, although the latter stirs more controversy.”

Both culture and skills are involved in differentiating various racial and ethnic groups. Behind these skills are cultural values that prioritize the acquisition of new skills and emphasize the shedding of obsolete ones, showing, once again, that cultural achievements among groups are far from random or evenly distributed.

The overarching theme that Sowell seems to return to repeatedly on the issue of race is the belief that character, culture, and effort are meritorious. The scales of success or opportunity should not be tipped in favor of black people at the expense of other Americans merely because black Americans descend from slaves. The scales of success should be tipped in favor of merit. This approach to merit, like the belief in the idea of racial color-blindness itself, is aspirational, but it is certainly a worthy goal to constantly keep in mind and strive toward in a country as diverse as the U.S. Importantly, many of Sowell’s insights on race reaffirm the fact that black people are no different from other ethnic groups in America who strive to rise above their humble beginnings. Contrary to the claims of Sowell’s critics, nowhere in his writings does he deny that the majority of black people were introduced to America through slavery. However, he does deny that black Americans are permanently scarred by the experience of slavery and therefore in need of perpetual government handouts.

Time and again, Sowell is ruthless in marshalling facts to analyze a claim or social policy. One claim that he has very little tolerance for is the belief that slavery and postslavery discrimination left a legacy of broken families among black Americans. He convincingly shows that the data on the black family say otherwise. For example, the proportion of black children living with one parent was not significant “during the first hundred years after slavery as it became in the first thirty-five years after the great expansion of the welfare state, beginning in the 1960s.”

Sowell argues that the causal connection between the breakdown of the black family and the growth of the welfare state in the lives of black Americans is empirically verifiable for those willing to look at the historical record. As a matter of fact, the historical record has been evaluated by a number of scholars and writers over the years, going back to E. Franklin Frazier, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, George Gilder, Charles Murray, and William Julius Wilson. The most recent review of the historical record regarding the breakdown of the black family and the growth of the welfare state in black communities has been done by Jason L. Riley of the Wall Street Journal in his book The Affirmative Action Myth. Sowell’s claims about the causal connection between the breakdown of the black family and the growth of the welfare state have been empirically verified as true, many times over.

It goes without saying that Thomas Sowell is a formidable presence in American intellectual life. The books I have mentioned, along with the ideas they convey, represent only the tip of the iceberg in terms of his scholarly reach, accomplishments, and enduring influence. Sowell’s intellectual palette is both wide and deep. Beyond academia, his biography affirms the promise of America for those with initiative and determination: success.

Andre Archie is an associate professor of philosophy at Colorado State University. His latest book is The Virtue of Color-Blindness.