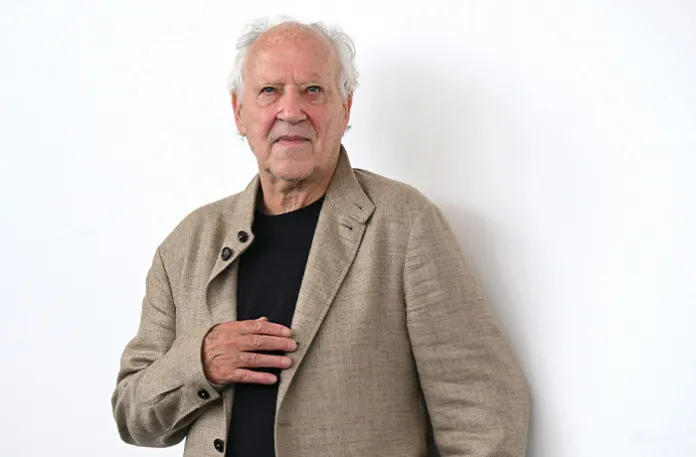

Werner Herzog has become a beloved icon in a culture that would absolutely not accommodate a young Werner Herzog. He was an ambitious, unpredictable auteur; now cinema is far more corporate and predictable. He was a fearsome risk-taker, shooting in warzones, threatening Klaus Kinski, and eating a shoe, and now health and safety protocols would constrain him. Still, we listen to a man like Herzog, perhaps to tell us what is going wrong.

The Future of Truth is a short and digressive book that does the last thing we expect from the output of beloved cultural icons — it challenges us. In a time where “fake news” and artificial intelligence have made a lot of us concerned about defending facts against falsehoods, Herzog has turned a skeptical eye toward facts.

This has been a key theme of Herzog’s career. “All my life my work has been involved with the central issue of truth,” he writes. “I have always vigorously opposed the foolish belief that equates truth with facts.” In his “Minnesota Declaration,” Herzog dismissed the primary significance of “the truth of accountants” and celebrated “ecstatic truth,” which is “mysterious and elusive, and can be reached only through fabrication and imagination and stylization.”

The Future of Truth develops this theme. Art, Herzog reminds us, does not just report on what has happened, or what is happening, but animates it. Herzog uses the example of his friend Bruce Chatwin, who was a dubious journalist inasmuch as he would blend facts with fabrication, but a brilliant writer inasmuch as he could draw out aesthetic and philosophical meaning. In Patagonia might have contained elements of fabulation, but its poetic resonance still meant that it imparted more truth than a dry but accurate account of life in South America could have done.

After all, there is nothing necessarily interesting about facts. “There’s a book for people like you,” Herzog reportedly snarled at a critic who questioned his bona fides as a documentarian. “It’s called the telephone book. Everything in it is true.” That Herzog reading the telephone book in his iconic Bavarian drawl could be eminently listenable is perhaps beside the point.

Truth, Herzog suggests, can also arrive more revealingly when an element of artifice is involved. One chapter discusses Family Romance, a Japanese company that provides actors to “fill in” as partners and friends for lonely or secretive people, which Herzog made a film about in 2019 called Family Romance, LLC. Journalists who wanted to report on Family Romance asked to speak to one of their clients. The “client” turned out to be an actor himself. Yet the owner of Family Romance argued that an actual client would have been dishonest in an attempt to save face. Only his actors had deep insights into the kind of people who would hire them.

Yet at what point does deception become inexcusable? At the beginning of his film Lessons of Darkness (1992), Herzog writes that he attributed a quote which he had written to Blaise Pascal. “By using Pascal’s name,” he writes, “I give the quote the gravity it needs.”

“What’s critical here,” Herzog adds, “Is that I told the media about my attribution.” But that doesn’t mean the viewer got around to hearing that.

Does it matter? A good quote is a good quote, whoever wrote it. But artists like Werner Herzog do not need shortcuts to evoke profundity. And if misleading the audience can be legitimate, how can we distinguish between the honorable and the venal falsehood? How can we distinguish between the harmless and the harmful act of fabrication? Again, In Patagonia was a great book, but it would have still been a great book had Chatwin treated his subjects’ lives more carefully.

Of course, Herzog is not attempting to excuse falsehoods in general. He disdains the vacuous dreams of techno-optimists or the sinister mistruths of Holocaust deniers. But how can we “learn to tell fake news from the real thing?”

“We need to reinvigorate critical thinking,” writes Herzog. For him, this is not just an analytical exercise but a spiritual exercise. It does not just demand the scientific tips and tricks of epistemology. It demands that we become broad-minded and contemplative: reading real books and walking — “foot travel with almost no gear, elemental, dictated by deep need.” Herzog is getting at something true here. Critical thinking is not just about the granular business of distinguishing fact from fiction; it is about assessing their context and significance. It does not just demand intelligence and rigor, but at least some kind of wisdom.

Walking has a deeper significance for Herzog. For him, the search for truth is as much about the journey as it is about the destination. This might be because the process enriches us. But it is also because “ecstatic truth,” for Herzog, does not appear to be something that we can ever grasp in its totality. Rather, it is something “far beyond the reach of fact” which we can glimpse but never quite behold. As we walk, it appears and disappears behind the trees.

There is something to this. Has anybody ever closed their eyes, on their deathbed, in the blissful knowledge of complete comprehension? Cultists and lunatics. There is some extent to which truth will always elude us, just as one can never actually touch a rainbow.

Still, I closed The Future of Truth feeling a slight defensiveness on behalf of those narrow-minded phonebook browsers. Instead of the derisive term “the truth of accountants,” let us think about the truth of detectives. There are few more timeless themes than murder. Poets, painters, and directors can reflect — and have reflected — on the social and psychological implications of murder. But if one takes place, you don’t call a poet. This is not only for the basic reason that you want the murderer jailed. It is because broad truths spread out from narrow truths. The narrow truth is insufficient, but it is essential.

A more specific example is troubling me. Klaus Kinski, who acted in many of Herzog’s films — such as Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1976) and Fitzcarraldo (1982) — embodied and, in doing so, illuminated ecstatic truths. He behaved, on camera, as no human would behave. In a literal sense, he barely even looked human. But no one has ever represented archetypes as compellingly as this volatile and destructive performer. A more “realistic” actor could not have come close to representing desire, hubris, and insanity with the style that Kinski could.

MAKING MAGIC: REVIEW OF ‘THE MASTER OF CONTRADICTIONS’ BY MORTEN HØI JENSEN

In 2013, one of Kinski’s daughters, Pola Kinski, alleged that her father had raped and abused her. Her sister, Nastassja Kinski, has said that she believes her (as, indeed, has Herzog). The point is not just that the truth of such incidents matters — as if anybody would deny that. It is that mere facts can have their own tremendous urgency. My point is not that Herzog would disagree. It is only that it deserves restating.

That said, we should celebrate Werner Herzog for his restlessly inquisitive career. In his 80s, he remains a challenging and thought-provoking commentator on the modern world. To read or watch his work is to be informed but also to be inspired — to be inspired, that is, to take up one’s pack and walk, in a metaphorical sense, with one’s own intellectual or artistic work, or in a very literal sense. He is correct that the search for truth will only end with the extinction of intelligent life. For all that man has learned, and for all that man has lied about, the truth is still out there, glimmering between the trees.

Ben Sixsmith is the online editor at The Critic.