For decades, Mississippi was the poorest state in the union. Like Ireland, its most important export was its own people, leaving in search of economic opportunity elsewhere. Mississippi’s economy started to improve in the early 2000s, when then-Gov. Haley Barbour (R-MS) initiated the Momentum Mississippi program to draw investment into the new sectors of financial services and high-tech manufacturing. The groundwork paid off. The Bureau of Economic Analysis calculated that Mississippi’s GDP grew from $66 billion in 2000 to $139 billion in 2022. In the last five years, Mississippi has grown more than in the previous 15 years.

Mississippi’s rise is part of a wider Southern success story. By May, eight of the 15 fastest-growing cities were in Texas or Florida, the states at the heart of the South’s economic boom. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, the South’s population has grown by 5.6% while the Northeast’s population has grown by just over 1%. The increase in population by roughly 7 million has helped to push real GDP growth to an annual rate of 4.3% since 2020, compared to 3.6% nationally and 2.9% in the Northeast.

While the South booms, the European economies are falling behind the United States. “Europeans can’t afford the US anymore,” Le Monde’s New York correspondent told the French in April 2024. “The gap with European living standards has never been wider.” A 2024 study by Patrick Artur for the Institut Polytechnique de Paris dismissed the idea that differences in the working-age population explain why Europe is lagging. The reasons are structural: a high-regulation, high-tax environment, and aggressive environmental policies that were already raising Europe’s energy costs before the Ukraine war broke out in 2022.

The economic drag of European policies became apparent after the double shock of the 2008 Great Recession and the Eurozone debt crisis, which began in 2009. Between 2010 and 2023, the cumulative growth rate of GDP in the U.S. was 34%, compared to 18% in the Eurozone. Labor productivity grew by 22% in the U.S., but only 5% in the Eurozone. Britain’s relative decline has been even sharper.

“The average U.K. person will this year have a greater income than their U.S. counterpart for the first time since the 19th century,” the BBC claimed in January 2008. That year, strong economic growth and the relative weakening of the U.S. dollar drove British GDP per capita to $47,396, just ahead of the American figure. Since 2008, however, British GDP growth per capita has almost stagnated at around 1% a year — slower than Germany and the Eurozone. Again, policy choices have consequences.

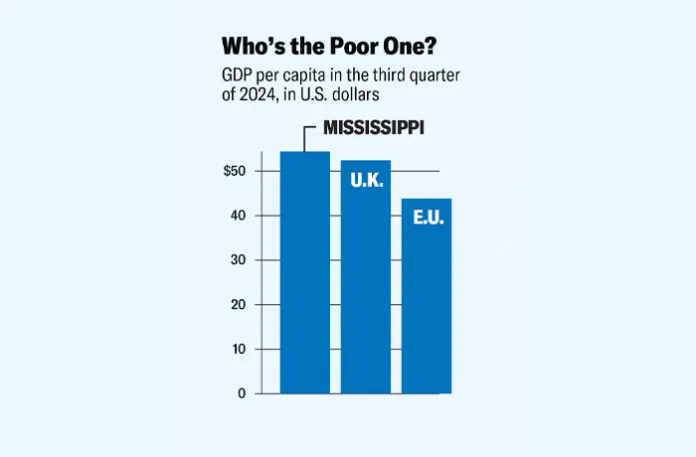

In 2014, Fraser Nelson, then the editor of the Spectator, noted that “if Britain were to somehow leave the EU and join the U.S.,” it would be the second-poorest state in the union in terms of GDP per capita: “Poorer than Missouri. Poorer than the much-maligned Kansas and Alabama.” An analysis by the Financial Times confirmed that Britain would be poorer than Mississippi, too, if London and its suburbs were subtracted from the British figures. A decade of sleepwalking and self-harm later, in January 2025, data from the International Monetary Fund’s Global Outlook Report answered what the media were now calling the Mississippi question: Was your European social democracy actually poorer than America’s poorest state? Mississippi’s GDP per capita income in the third quarter of 2024 was $53,872. Britain’s was $52,423. The EU’s was $43,353.

The Mississippi question

“All the great economic and technological innovation in America is now happening in the South,” Douglas Carswell told me. Carswell, a tall, serious man with a vaguely military manner, served as a Conservative member of Parliament from 2005 to 2017. In 2014, he left the Tories and became the U.K. Independence Party’s first elected MP. This win helped trigger the 2016 Brexit referendum, in which Carswell, a co-founder of the Vote Leave campaign, played a key part.

“The struggle to get Britain out of the European Union was absolutely crucial, but it’s only part of a broader story about liberty and the Anglosphere,” Carswell explained when we met in Washington. “The real battle of our time is whether or not the American republic retains its exceptionalism. And I want it to be part of that.” He looked at a couple of roles in the capital, but he kept noticing that “all the great policy innovations come from the states.” In 2021, however, Carswell left Britain and joined the Mississippi Center for Public Policy, where he is now the president and CEO.

“I wanted to be here because I think that if the conservative movement in America has a future — and that’s an open question — it’ll have a Southern accent,” Carswell said. “It’s fair to say that 150 years ago, the North saved the Republic. I think the South and the Southern conservative model is the best hope of saving the Republic.”

Carswell was drawn to Mississippi as a test bed for free-market theories. He arrived as the effects of regulatory reform and pro-business policies started to snowball. “There have been three really big strategic changes in the past five years,” he said. The recipe for economic revival is labor market flexibility, low taxes, and low-cost energy.

“The first really significant change happened in 2021 when we achieved labor market deregulation,” Carswell said. “We were already an at-will employment state, but there was still a lot of old restrictions dating back decades. Politicians talk about workforce development because that makes it sound like they’re doing the developing. But actually, occupational licensing reform is the key thing.”

Occupational licensing meant that the labor market was theoretically free but actually restricted. “You needed several hundred hours to get a license to cut someone’s hair,” Carswell said. In 2021, Mississippi’s universal occupational licensing law shaved off the regulatory restraint. “The law means that if you are licensed and credentialed in another state, you can automatically get approval in Mississippi.” This, in turn, raised pressure inside Mississippi for Mississippians to ask the authorizing board, “Why the heck should I have to do 500 hours of training to become a hairdresser when Bob from across the state line can get a license?”

The second factor was tax cuts. In 2022, income tax in Mississippi became a flat rate of 5%, falling to 4% in 2026. In 2025, the state passed legislation that could lead to eliminating income tax entirely. “Why does that matter? One, if you’re an employer investing in Mississippi, it means your payroll is significantly lower,” Carswell said. “Two, if you’re making a long-term investment decision in Mississippi, you’re making it for a 20- or 30-year period. We’re already seeing the positive benefits of the 5% corporate tax rate. So big investors now know that these costs are going to go down further.”

The tax cuts attracted a flood of investment. “There’s been $42 billion worth of inward investment in the past five years in Mississippi,” Carswell said. In the last six months alone, the Mississippi Economic Development Council reported, GE Aerospace expanded manufacturing capacity at its Batesville site. Delta Utilities, a Louisiana-based natural gas supplier, bought three local distribution sites with the aim of upgrading the infrastructure. Howard Industries, a Mississippi-owned manufacturer of electrical distribution technologies, announced a $236 million expansion at sites across three counties to meet demand for power from data centers and electric cars. Northrop Grumman expanded its in-state presence by opening a research lab at Northeast Mississippi Community College’s Corinth campus. Averitt Express, a freight distribution and supply firm, announced a $9 million expansion.

The state announced the largest grid upgrade in Mississippi history and engaged Entergy Mississippi to build a $1.2 billion, 754-megawatt combustion turbine power plant on the site of a former electric plant in Warren County. This encouraged Amazon, which had already committed to investing $10 billion for data center campuses in Madison County, to invest $3 billion in a new data center in Warren County — the largest single private investment in the county’s history. Toyota, which intends to invest $10 billion over the next five years at plants in West Virginia, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Missouri, announced a $952 million investment at its Blue Springs plant, where America’s first electrified Toyota Corollas will be assembled.

The third factor is low energy prices. “Mississippi’s energy costs are low, largely by sidestepping and avoiding the Obama-era and Biden-era green renewables,” Carswell said. “There’s a little bit of those around, but basically, energy is not subsidized. And Mississippi is a very sunny part of the world. I dare say that at some point, home-installed solar paneling will become economically viable. In fact, Tesla’s already starting to sell. But the idea that you should have government-sanctioned renewables is for the birds. That’s why electricity costs are so low, and it’s why you get data centers.”

In the last quarter of 2024, Mississippi was the second-fastest-growing state in America. In the first quarter of 2025, it was the fifth-fastest. University enrollments are rising as students avoid the woke campuses of the Northeast. The population is rising, too. Like Ireland, Mississippi is importing people for the first time in decades.

“The idea that America deindustrialized and the jobs all went to China and Vietnam is nonsense,” Carswell said. “They went south. Mississippi and Alabama combined now make more cars each year than the U.K.” He paused. “If only the U.K. did something similar.”

Millstones and milestones

England is about the size of New York state. Like an American state, Britain is both subject to a federal regulatory system — in Britain’s case, through its voluntary subscription to EU standards — while having considerable leeway in setting its own regulatory terms. Like New York state, Britain’s economy depends on the financial services industry in its capital. Like Mississippi, Britain specializes in a couple of strategically important industries — in Britain’s case, defense technology, biotechnology, and artificial intelligence. Unlike Mississippi, Britain is an innovator. Could Britain adopt the Mississippi model?

“It doesn’t matter whether you live on a rock in the North Sea or in the most fertile part of Italy,” Carswell said. “If you’ve got the right human capital, you can create wealth. If you get rid of restrictions, you will create wealth. The U.K. is even more blessed by natural resources than Mississippi, and it’s got phenomenal universities.”

The obstacles are not just regulatory but also cultural. When Carswell was in Parliament, his fellow Conservatives dismissed him as a “maverick” for defending national sovereignty and free markets, ideas that Britain once distributed around the world. “It’s been quite a revelation for me to come to a place where conservatives actually want to do conservative things,” he reflected. “Lawmakers in Mississippi compete to come up with conservative ideas. They’re very approachable. Send them a text message, and they’ll say, ‘Can we meet to discuss that idea?’ British Conservatives regard people advocating for actual conservative policy as a mild irritation, at worst an embarrassment.”

He suspects that the crunch is coming. “I don’t think [late British Prime Minister Margaret] Thatcher would have been possible without a sense of crisis. You needed to have a sense of desperation.” The scale of Britain’s problem is, however, much greater. “Thatcher came in with a script and an agenda to right a country that was sinking economically. An incoming right-of-center government has an even bigger task. Britain is not just failing economically. It is in catastrophic demographic and social shape.”

Britain has accumulated the kind of high taxes and high regulations that should induce economic contraction. Growth has been sustained, Carswell said, by “vast quantities of stimulus.” Economic revival becomes a double problem. Tax cuts and supply-side reforms are not enough: The economy still faces “one heck of a fiscal hangover.” Add to this a large number of low-skilled workers and “a huge problem with welfare-dependent foreigners living in the country.” Economic restructuring cannot succeed without addressing the hitherto “sensitive subject” of immigration. “It can’t be swept under the carpet,” Carswell said. “You’re going to have some element of remigration. It needs to be done. If you are in the country illegally, you need to leave. America does that now.”

The American precedent is much on Carswell’s mind as Britain’s crisis deepens. Nigel Farage, who, based on current polling, will win the next elections and lead his Reform U.K. party into government, now holds Carswell’s old parliamentary seat, Clacton in Essex. Carswell believes that Reform U.K. will achieve office but fears that, like the first Trump administration, it may struggle to wield legislative and bureaucratic power.

“Trump 1 went to war with the administrative state, underestimated its intransigence, was thwarted, and ended up having to hire family members because it couldn’t trust anyone. You can complain to the TV cameras that you’re being thwarted by the judges and the civil servants, and nothing gets done. Then you’re in real trouble.” Carswell is trying to ensure that when the British elect a leader to dig them out of the ditch, he will have the tools to effect rapid legal and bureaucratic change, as the second Trump administration did in its opening months.

In March, Carswell published a long paper in the London Telegraph, laying out the nine “milestones” for structural reform in Britain, with 34 specific policy “stepping stones.” The first three milestones would restore democratic legitimacy by reining in the civil service and the courts; empower the prime minister by creating an American-style Department of the Prime Minister; secure the borders, expel illegal immigrants, and revise immigration law; undo the “Blairite legislative legacy” that has hived off power to unaccountable nongovernmental organizations and bureaucrats; cancel climate change legislation and bring in a Free Speech Act.

The second three steps are “radical deregulation” and the Mississippi cure for the economy. Though Britain left the EU in January 2020, some 19,000 EU regulations remain on the books. Drug approvals, for instance, take 12-18 months longer in Britain than in the U.S. Britain now has its highest taxes since World War II. Income tax and red tape must be cut, corporation tax reduced, and employment law loosened. Universal healthcare is part of the social compact, but it is bankrupting the country. It can be secured by a “Singapore-style” hybrid, in which taxpayers pay a low single-figure sum into a mandatory health savings account. Mississippi, which still tops the league for poverty among U.S. states, could benefit from that.

BBC EXISTS TO SUSTAIN ITS MONOPOLY

The last three milestones are education reform, including vetting Muslim schools that teach extremism; increasing defense spending and realigning foreign policy toward the Anglosphere; and paying for all this through DOGE-style cuts across the bureaucracy.

“If the laws of physics are the same in the U.K. as they are in America, which they obviously are, then all of this can and should be applied,” Carswell said. “A 90-day at-will labor law would solve a lot of Britain’s labor force problems. You’ve got even more hydrocarbons underneath Britain than there are under Mississippi. The South is blessed with lots of oil and gas, but Britain’s got even more. Why the hell aren’t you using it? And the U.K. can’t afford not to have tax cuts. Do it right, and you create a virtuous circle.”

Dominic Green is a Washington Examiner columnist and a fellow of the Royal Historical Society. Find him on X @drdominicgreen.