In January 2020, a few weeks before the entire world experienced one of the greatest social and economic disruptions in memory in the form of the COVID-19 pandemic, a billionaire wrote an email.

“When 70% of Millennials say they are pro-socialist, we need to do better than simply dismiss them by saying that they are stupid or entitled or brainwashed; we should try and understand why. … When one has too much student debt or if housing is too unaffordable, then one will have negative capital for a long time and/or find it very hard to start accumulating capital in the form of real estate; and if one has no stake in the capitalist system, then one may well turn against it.”

The author of that email, tech investor and entrepreneur Peter Thiel, was speaking of the need to listen to the causes propelling a growing economic disillusionment among younger generations. At the time, millennials were the youngest generation that had fully aged into the workforce. Generation Z was just barely stepping into entry-level roles, and much of the generation had yet to graduate high school, let alone college. And that was all before they experienced the largest economic disturbance since at least the 2008 Great Recession that supercharged the very issues that Thiel identified as a barrier toward the accumulation of capital: student loan debt and unaffordable homes.

But while Thiel correctly observed that economic conditions were driving a generation of young people away from the principles of free enterprise and free markets that undergird America’s economic might, his email does not capture the full picture. It is one thing to say that heavy debt and the inability to buy and own a home are driving people away from capitalism, but it is another to recognize that interest in socialism as an alternative is as much due to the education that debt paid for as it is to the economic conditions that made it attractive.

Surveys from major pollsters have consistently shown that, while Thiel’s 70% assessment may be a bit of an exaggeration, younger generations are far more likely to support socialism or oppose free enterprise than older ones. A 2022 Pew Research Center study showed that 73% of respondents aged 65 or older held a positive view of capitalism, as did 62% of those aged 50-64. Among the first age group to include millennials, 30-49, that support dipped to 53%. Among respondents aged 18-30? Only 40% held a positive view of capitalism, while 44% felt drawn to socialism, the highest of any age group.

As Thiel noted, this generational shift against America’s traditional economy, in which people are free to invest and take risks as they choose, cannot simply be dismissed as the folly of youth. The reason that pro-socialist sentiments were able to take hold was due, in no small part, to failures of the system as it is now. But it was also the fruit of a political and cultural project that long predates the economic difficulties that young people face today.

On Oct. 18, hundreds of thousands of people turned out to protest against the Trump administration, using the self-righteous slogan “No Kings” as their rallying cry. This was the second such protest of the year, but with a much larger turnout than the June 14 event.

While the protest numbers were impressive, running into the millions, one could not say the crowd was dominated by socialist-curious young adults. Instead, it was largely made up of baby boomers, a generation that came of age at a time when significantly more people were attending college, who made public demonstrations, political protests, and social rebellion an integral part of their early adulthood.

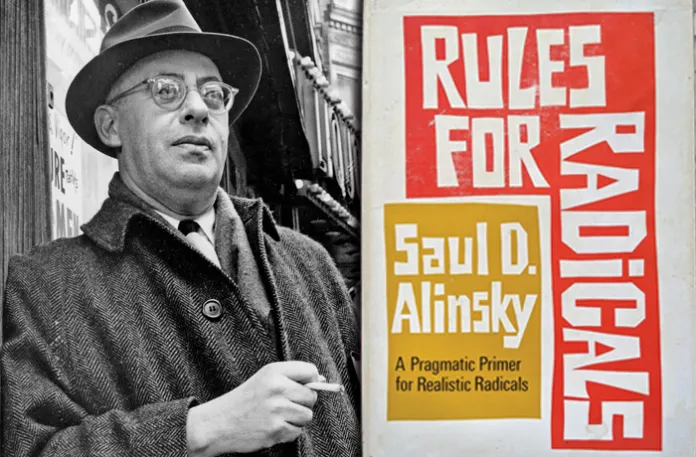

But while the crowd was largely composed of people in their 60s and 70s reliving their fondly remembered days of protest of their youth, that didn’t mean young people disillusioned with their lot in life did not also join the “No Kings” fray. In this way, the Oct. 18 protests were part of a decadeslong social and political movement that has entrenched itself in the college campuses, following the guidebook of social organizing, Rules for Radicals, written by Saul Alinsky.

It is hardly a secret that American higher education has been a bastion of leftist and progressive thought and activism for decades. In the 1960s, the University of California, Berkeley, famously descended into chaos as the “Free Speech Movement,” spurred by support for the Civil Rights Movement and opposition to the Vietnam War, staged a highly publicized and disruptive demonstration that culminated in mass arrests. In 1968, students at Columbia University likewise occupied campus spaces, grinding regular teaching and other activities at the university to a halt and precipitating a large police response.

Today’s socialism-sympathizing millennials and Gen Zers were not even born when Jack Weinberg and Mario Savio, the architects of the Berkeley Free Speech Movement, plunged the California university into chaos. Nor were they born when antiwar protesters at Columbia shut down the New York City campus in 1968. These disruptions were the doing of the very baby boomers who flooded the streets for the No Kings rally this year.

But today’s college students and recent graduates were educated by many of the same radicals of that era. Bill Ayers, a founder of the Weather Underground, a violent left-wing group that carried out bombings at several federal facilities in the early 1970s, was a professor for years at the University of Illinois Chicago after receiving a doctorate in education from, of all places, Columbia.

It is the impulse of youth to rebel against what came before, and Ayers, the Weather Underground, and the disruptive protests of the 1960s were part of that trend. But while Ayers spent his idealistic youth as a domestic terrorist intent on overthrowing the U.S. government, rebelling against the establishment, he spent the rest of his career institutionalizing the ideas that had driven him to violence in his younger days. One might say that as he matured, he realized the best way to achieve his political ends was not to destroy the established order, but rather, to co-opt it, corrupt it, and replace it.

In this way, Ayers, whether consciously or not, admitted the project of his youth was a failure. Instead, he vindicated the approach of another Chicago radical in Alinsky, a mentor to one Hillary Rodham Clinton and an inspiration to former President Barack Obama. While Ayers sought the overthrow of the existing political order by force, Alinsky’s guidebook of political and community organizing sought to undermine and replace that order from within its own rules. As Alinsky put it, his rules “make the difference between being a realistic radical and being a rhetorical one who uses the tired old words and slogans.”

One can see the influences of Alinsky in many of the leftist social movements of the 20th and 21st centuries: the Vietnam War protests, Occupy Wall Street, and Black Lives Matter, to name a few. But just as Ayers shifted from bombings to academia in the 1980s, the Alinsky model of community organizing evolved from the work of students and outside disruptors and became entrenched in academic programs themselves. Thus, Alinsky’s ideas found their way into college curricula everywhere, as public and private classrooms alike cultivated and trained “radicals” committed to social upheaval, from the undergraduate level up through various graduate programs, and including at the nation’s most prestigious institutions.

The law schools at Harvard University, New York University, and Columbia are among the institutions that have integrated the Alinsky model of community organizing into their course curricula. Harvard offers a program of study titled Law and Social Change, which it describes in phrases that might as well have been plagiarized from Alinsky’s book.

Here is a sample: “People are at the heart of social change. So, then, are deliberate strategies to organize people, to mobilize groups with shared interests, to forge social movements, and to connect these efforts to law. The question of how law can facilitate organizing – how law can contribute to the building of social movements by enabling associations to meet, raise funds, speak, and act or by offering targets and arenas for action – is an important theme. The role of intellectuals and intellectual movements in social movement work is also an important area of study.”

Not coincidentally, Rules for Radicals has become required or recommended reading in courses at numerous institutions, many of which explicitly use Alinsky’s book as the model for community organizing. The University of Texas at Arlington, a public institution, listed the book as recommended reading for a class on “Community and Neighborhood Organization.” The current course description says the class places “special emphasis” on “poverty and minority communities and neighborhoods.”

Jeff Miller, a professor at Utica University, cited Alinsky as his inspiration for his course “Community Organizing,” which is offered as part of the course of study for the university’s communication and media major with a concentration in social justice. “I start with Alinsky’s simple definition that power is the ability to act, and that this is power to do, not power over,” Miller said in a university profile on the course. “So, in the context of a free and open democratic society, power means being recognized, if not respected, in the public decision-making process, where most decisions tend to be about allocation of resources, of who will get what.”

While examples of the book’s placement and influence in specific courses abound, the broader project of community organizing for political and social ends for the “have-nots” against the “haves,” as Alinsky put it, has instead found a place with the “haves.” It is an ironic twist of fate that what Alinsky described as a book about seizing power and giving it to the people has not been taken up by its supposed beneficiaries nearly as enthusiastically as it has by those who are in positions of power and influence. It has morphed into a guidebook for maintaining power and keeping it away from those who would challenge the Left’s institutional control of education, pop culture, government bureaucracy, and nongovernmental organizations.

Likewise, when it comes to the modern Left, there is a paradox within the ranks of those young people who identify with it, thinking that to be on the Left is somehow still countercultural. Unlike the aged generation that mainstreamed campus radicalism decades ago in the 1960s and 1970s, those who embrace the Leftist or socialist project today are fooling themselves in their belief that they are rebelling against the status quo; what they are really doing is conforming to the cultural establishment.

In this sense, Ayers’s project of institutionalizing his radical ideas was successful. The self-described “small ‘c’ communist” came of age in an era where supermajorities of the public opposed communism and socialism. When he realized that a campaign of violence would not achieve his ends, he switched tactics, joining a cadre of like-minded academics all over the country who turned college classrooms into training grounds for radicalism. Few can argue with the results. Ideas that were once considered radical have ceased to be anything beyond orthodox in academic circles. They have become or are increasingly becoming the cultural and social norm.

At its core, the Rules for Radicals playbook for community organizing is about how to communicate radical ideas in a way that extends and popularizes their appeal. But even among the naive and impressionable college students and recent graduates who have been taken up by its promise of social change, empowering the “have-nots” against the “haves,” that message can take hold only if there is a widespread belief that society is so fundamentally broken that radical social change is required.

Which brings us back to the Thiel email from 2020.

To understand why young people in particular are interested in socialism, one only needs to look at how socioeconomic circumstances have provided the fertile ground in which the seeds of radical change, once sown, would germinate, take root, and spring into life.

The leftist capture of higher education is not a new phenomenon. Ayers, after all, taught at UIC throughout the 1990s and 2000s. The Marxist feminist activist Angela Davis, who, for a long time, was a card-carrying member of the Communist Party USA, taught at the University of California, Santa Cruz, through much of the same period, 25 years after she was fired from a teaching position at the University of California, Los Angeles.

But what is new is the interest in a radical upheaval of the nation’s economic system. Even in institutionally radical academia, socialism or communism preached and organized along lines laid down by Alinsky did not gain hold of young people until fairly recently. Even among millennials, long considered a liberal demographic, support for socialism has support among a substantial minority, but it is a minority position nonetheless.

In 2000, according to the Federal Reserve, people under 40 held 9% of the nation’s wealth. The same age group also held nearly 18% of the nation’s real estate wealth. But in 2010, after the 2008 financial crisis, that age group held only 4% of the nation’s collective wealth. While that age group has seen a slight recovery since then, the 7% of wealth it now holds is still below what it was in 2000. In the same time period, the share of the real estate market held by those under 40 fell by one-third in 2010 to 12%, where it has stayed ever since.

The wealth held by older generations has vastly increased. In 2000, people 70 and older held 20% of the nation’s wealth and 18% of real estate. In 2025, those percentages increased to 26% of real estate and 32% of all wealth.

The generational divide in wealth accumulation explains a large part of the appeal of socialism to young generations. One can point to a myriad of reasons for lower wealth among younger people — enormous student loan debt, excessive consumer spending, a lower marriage rate, a lack of new housing construction — but when economic stability seems further and further out of reach and this experience is common among peer groups, it is easier and easier to believe that the system is what must change.

When older millennials and the tail end of Generation X came of age at the turn of the century, that was not the case. Economic stability and wealth accumulation felt within reach. But then the economy crashed, the housing market was turned upside down, Obama’s promise of hope and change never panned out, and social isolation skyrocketed with the advent of the smartphone and later the pandemic.

THE MAGA COALITION NEEDS ITS INFIGHTING

Amid all of that socioeconomic chaos, the promise of radical change, the sort preached and taught by Ayers, found a built-in audience in the college students who already believed the deck was stacked against them.

Their solution, pressed by radical teaching at colleges and readily believable because of their circumstances, is to tear down the deck. Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals provides students of revolution with their textbook.

Jeremiah Poff is the Restoring America editor for the Washington Examiner.