Ours is an era in which elected officials, like public figures more generally, have by and large abdicated their responsibility to model good behavior. Once, politicians felt compelled by the sweeping visibility of their office to demonstrate an outward sense of virtue, decorum, and etiquette. It would have been inconceivable for President John F. Kennedy to have cursed in public — it was even shocking to hear the comparatively salty and sweaty Richard Nixon do so in private on those notorious audiotapes. George H.W. Bush dressed the part of a president, and Bill Clinton tried to. Presidents not only sought to project confidence in times of crisis, as they still strive to do, but also to communicate dignity and propriety every time their likeness might be captured by a camera.

Things change. Over the course of his three presidential campaigns and pair of administrations, Donald Trump has sanded down our seemingly innate resistance to hearing and seeing presidents do unpresidential things. Trump can deploy bad language or summon rude jokes, and the nation shrugs. To his many admirers, such behavior is an indication of the urgency of our times — there is no time for pearl-clutching when the country is on fire. That may be true, but this toothpaste cannot be put back in the tube: Even if America is made great again, it seems unlikely that any future aspirant or occupant of the highest office in the land will corral his or her baser impulses — just consider the conduct of Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-CA), the 2028 Democratic presidential contender and Trump social media imitator.

This makes all the more startling, in a heartening way, Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy’s recent exhortation for air travelers to dress their best in advance of Thanksgiving as part of a “civility campaign.”

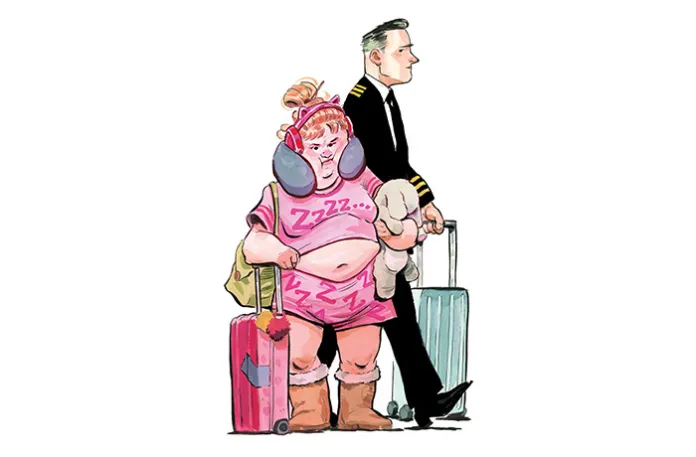

“Maybe we should say ‘please’ and ‘thank you’ to our pilots and to our flight attendants,” Duffy said. “I call this just maybe dressing with some respect. Whether it’s a pair of jeans and a decent shirt, I would encourage people to maybe dress a little better, which encourages us to maybe behave all a little better. Let’s try not to wear slippers and pajamas as we could to the airport.”

So, as it turns out, the Trump administration has not altogether neglected its obligation to “nudge” — to invoke an Obama-era term popularized by Cass R. Sunstein and Richard H. Thaler in their book of that title. Nudging can be very bad, and sometimes, as when the public was all but compelled to receive the COVID-19 vaccine to participate in the main currents of society, it can be far more than nudging. But Duffy’s nudging was not only mild but entirely salutary. In recent years, numerous well-publicized incidents over the years have seen airplanes become sites of teeming incivility. If even the very modest suggestion that travelers wear “jeans and a decent shirt,” to say nothing of a coat and tie, can work to improve passengers’ manners, who can complain? There is nothing but good that can come from encouraging travelers to start caring about how they come across in public.

Of course, most travelers by air, train, subway, bus, or rideshare would be surprised by the notion that they are operating in “public” at all. Over the last quarter-century, private habits have increasingly intruded on public activities, including travel, and especially when it comes to manners of dress. Just as contemporary movie theater operators redesigned their venues according to the principle that ordinary people will only buy tickets if offered a reasonable approximation of the La-Z-Boy in their living room, the leaders of airlines and other forms of mass transit have long seemed resigned to the fact that their patrons do not want to look good when utilizing their conveyances but merely want to be comfortable. Indeed, most people take no more effort in dressing for travel than they do in going to the gym or working in the yard — perhaps less. Theoretically, part of the joy of travel, even travel with a utilitarian purpose, such as a business trip, is making contact with strangers the traveler would not meet in the ordinary course of life, but the notion of wanting to leave a good impression on such people — on engendering a compliment about one’s tie or luggage, or representing well one’s home city — is a luxury that cannot be afforded by those to whom a pair of Crocs or flip-flops is the only essential travel companion.

In the specific case of air travel, the fact that pilots and flight attendants still don uniforms represents something of an aberration — a final confirmation of Tom Wolfe’s observation, in his 2000 book Hooking Up, about the radically divergent fashion styles present in luxe apartment buildings on Manhattan’s East Side at the turn of the millennium. Wrote Wolfe, “A doorman dressed like an Austrian Army colonel from the year 1870 holds open the door, and out comes a wan white boy wearing a baseball cap sideways; an outsized T-shirt, whose short sleeves fall below his elbows and whose tail hangs down over his hips; baggy cargo pants with flapped pockets running down the legs and a crotch hanging below his knees, and yards of material pooling about his ankles, all but obscuring the Lugz sneakers.” So, like the airline personnel still compelled to wear uniforms even as their passengers dress like slobs, the doorman retained a sense of propriety that was deemed eminently skippable by the apartment building’s luxe but louche inhabitant.

The purveyors of casual dress — in truth, the overwhelming majority of the U.S. population at this point — have advanced like an invading army in spaces where taste and decency once reigned. Previous generations understood that to dress well en route to a destination, whether to a place of employment on a commuter train or to a Thanksgiving get-together via a cross-country flight, was an acknowledgment that the activity was more than simply a means to an end. If travel were merely a matter of being conveyed from one place to another, perhaps a degree of sartorial slovenliness or at least inattentiveness could be excused, but if it was an occasion, a custom of adulthood whose necessity should not obscure its charm, it made perfect sense that previous generations wished to look their best. Nice luggage was a popular graduation gift for good reason. Car coats and driving gloves were less common but not unheard of.

Indeed, many activities we take for granted today were regarded by our forebears as occasions. Indeed, in the little book To Manner Born, To Manners Bred, an etiquette guide prepared for students at Hampden-Sydney College but available to anyone who wishes to look and thus behave more appropriately, an entire section is devoted to explicating “what to wear when.” Even today, many readers might not be surprised that a jacket or blazer with a tie or a suit is commended for church, or that a suit, “preferably dark,” is suggested for a funeral, but they will be surprised to find that some version of dressing up is advised at many other events.

For example, an athletic event is marked as a “casual” occasion, but the book notes that “at Hampden-Sydney a jacket and tie are traditional at football games.” (I can confirm that this practice was not unique to a tony Virginia college such as Hampden-Sydney: My mother attended her first Ohio State University football game in 1968 wearing a fur coat, and she never ceased to be amazed by the gradual takeover of branded sweatshirts and gear among the cheering fans.) In fact, there is a specific passage advising on the proper attire for “Travel when Representing the College”: “Jacket or Sweater with Tie (athletic trip), Jacket or Blazer with Tie, or a Suit (meeting or program).”

Dear reader, you do not have to be an alum of Hampden-Sydney to honor the spirit of this advice. By dressing better when on a plane, train, bus, or other form of mass transit, the public has nothing to lose and everything to gain, including their self-respect. The last point is not insignificant. Although Duffy’s exhortation frames dressing better as a first step toward acting better, thus making it something one does for others, the truth is that wearing a coat and tie, or a blouse and skirt, at bottom improves the morale of the wearer. That such attire works as a check on rude behavior is a bonus — the assumption being that if a lady has taken the trouble to wear pearls or a gentleman has taken the time to tie a bowtie, they will be less likely to act in such a way to muss their carefully worked-out appearance.

In the end, perhaps it is not surprising that the Trump administration, nominally so indifferent to the imposition of societal standards, is the source of this welcome plea for a more put-together populace. After all, the president alternates between two costumes from which he seldom deviates: his suit and his golfing attire. For all his uncouthness, the president has done his part to honor at least one tenet of the traditional role of commander in chief as role-model-in-chief: to avoid looking like a slob. That Duffy has vocalized what is implicit in Trump’s wardrobe is a cause for celebration. All is not lost. This Christmas, may visions of sugar plums dance in your head — and visitors bedecked in overcoats, scarves, and furs appear at your doorstep. Leave the slippers and pajamas at home.

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.