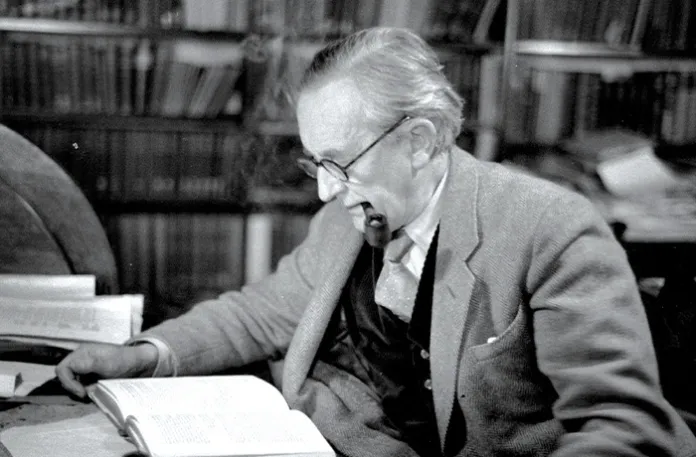

J. R. R. Tolkien was a poet at heart. Charmed by the sound of language, he was influenced by everything from the poem The Hound of Heaven by Francis Thompson to the plays of William Shakespeare to the Book of Isaiah to Anglo-Saxon works such as Beowulf and Christ I, a 10th-century Old English poem that begins with these lines:

“Hail Earendel, brightest of angels,

Sent to men over middle-earth,

And true radiance of the sun,

Fine beyond stars, you always illuminate

From yourself, every season!”

Tolkien called the lines “remote and strange and beautiful,” saying they made something come alive within him. They inspired one of his early poems, published in 1914, when he was only 22 years old. According to his son Christopher Tolkien, the literary executor of his father’s work, Christ I set in motion his writing career.

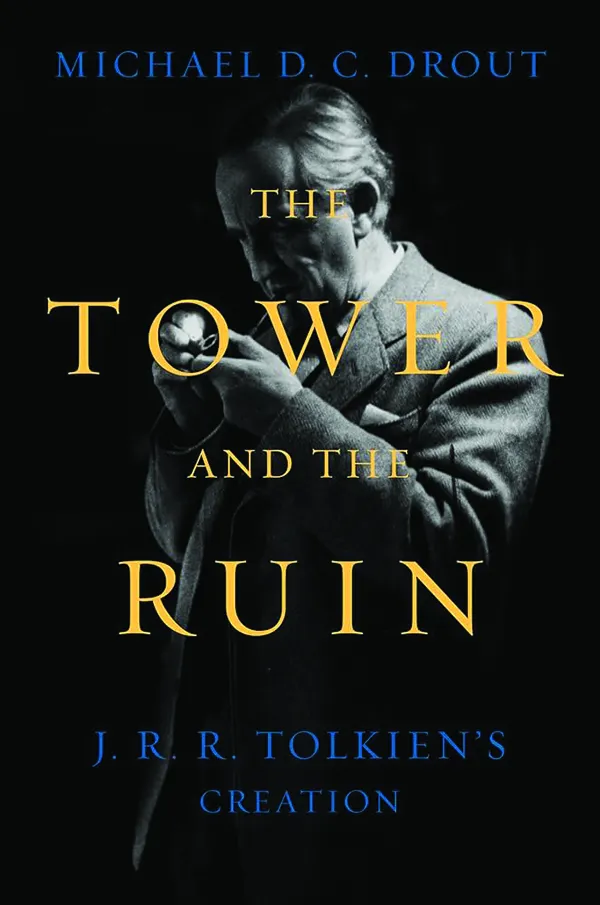

In his new book, The Tower and the Ruin, J.R.R. Tolkien’s Creation, English professor Michael Drout delves into Tolkien’s life and work while reminiscing about his own father and son, making his latest a moving blend of scholarship and memoir.

Tolkien was orphaned and raised by a priest, Father Francis Xavier Morgan. Morgan grounded him in religion and insisted he study at Oxford University before he was allowed to date Edith Bratt, his childhood sweetheart. They eventually married and had four children.

Tolkien studied Anglo-Saxon, Middle English, and philology at Oxford. He later taught there and became a member of the “Inklings,” a group of professors who shared their work. C.S. Lewis was another member. Tolkien’s The Hobbit was inspired by a musical-sounding line that came to him while he was grading papers and seemingly out of thin air: “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.” Tolkien said he continued writing to find out what hobbits were. Published on Sept. 21, 1937, The Hobbit sold out by Christmas. Its popularity prompted the U.K. publishing house George Allen & Unwin to ask for a sequel.

Although The Hobbit seemed to write itself, it took 17 years and many revisions before Tolkien’s masterpiece, The Lord of the Rings, came out in 1954. Comprising about 1200 pages and published in three volumes, the book is high fantasy and populated mostly with hobbits, elves, orcs, wizards, and dwarves. It is set in the imaginary land of Middle-earth and was partly inspired by the Finnish epic poem Kalevala, which combines culture, mythology, and folklore. (Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha was also inspired by Kalevala.)

Critics such as Edmund Wilson panned the trilogy, saying it is an out-of-hand children’s story. The book, though, was written for adults. Darker than The Hobbit, the trilogy, Drout says, is threaded with a feeling of heimweh, or homesickness, and deeply felt sorrow.

Drout says there is a feature in Tolkien’s work that engages readers more than in other works of modern literature. The purpose of his book is to understand that quality which he suggests comes from Tolkien’s ability to create far-fetched yet believable stories and his ear for poetry. Tolkien often wrote in an archaic style, immersing his prose in poetry, using the historical present tense, and infusing his writing with religious symbolism. His sentences have a musical quality and tend to be long and loaded with alliteration, metaphors, and Anglo-Saxon literary devices, such as runes, riddles, and kennings.

In one particularly poignant chapter of Drout’s book, the focus is on Faramir, a character in The Lord of the Rings who is mortally wounded and whose distraught father, Denethor, believing his son’s wound to be fatal, asks for his men to burn himself and his son. Drout seems to identify with Denethor’s sorrow, as he too nearly succumbed to despair when his son, Mitchell, died.

LIES, DAMNED LIES, AND POLARIZATION

Ultimately, Tolkien was a world-builder. He created Middle-earth, approximately 15 languages, and close to 1,000 characters, as well as six different kinds of creatures. Scholars say reading Tolkien feels like entering another universe. He frames his work around fabricated documents and histories. These give his books authenticity, making them seem like a reference to an ancient manuscript.

Tolkien said he starts with a word or phrase whose resonance catches his attention. He then follows the sound of the words — often not knowing the settings, plots, or characters of his stories until he has written several drafts. Then, as Drout describes it in this informative book, the words lead him to bright and profoundly engaging worlds. It is for the rest of us to explore them.

Diane Scharper is a regular contributor to the Washington Examiner. She teaches the memoir seminar for the Johns Hopkins University Osher program.