As you have begun to read this article, I will assume you are a reader. By this, I mean you regard reading creative works of literature as a good, sometimes delightful, and often beneficial way to spend your time. You know that reading delivers aesthetic and intellectual sustenance. You understand that it is not simply about achieving a minimum level of comprehension as one navigates modern life. Being that person, you will relish Good Bones: Glorious Relics from the Age of Reading, a collection of essays written over a span of a quarter century by literary critic Brooke Allen. They are elegant, erudite, and witty. They are also about good or very good writers whose work would be more valued if our civilization were not rapidly abandoning the best aspects of its traditional artistic culture.

In her preface, Allen writes, “We are in the middle of a seismic cultural change, as transformative as that which followed the appearance of the printing press half a millennium ago. And just as that invention turned the Western world into a literary society, we are now transitioning into a post-literate one … The authors I’ve covered in this collection, though all were famous in the very recent past, are figures that will probably disappear in the post-literate society, if they have not done so already.”

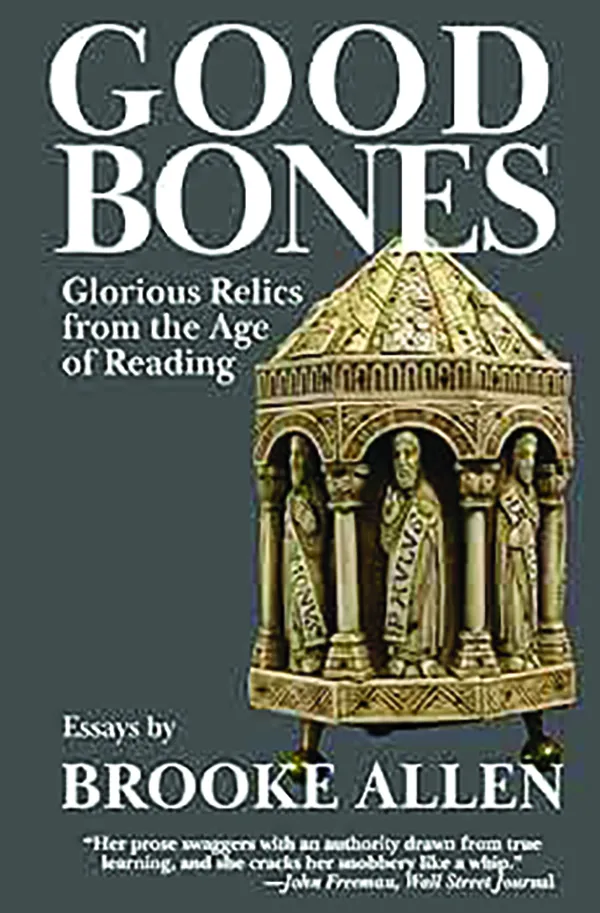

With each essay, and by bringing them together in one jewel-laden volume, Allen is engaged in an act of literary preservation and respect. On her cover is a photograph of a beautiful 13th-century ivory reliquary casket carved with the figures of eight apostles and symbols of the four evangelists. It is a sadly apt choice, for the artists and the works contained are, as she writes, “beautiful relics, the sacred bones of a literary culture being ground into dust by technology.”

The essays differ sharply from one another, which is natural since they were written over many years and for several distinctly different publications. The first and second essays, for example, which discuss the madness and probable fakery of August Strindberg and the grating and overweening narcissism of George Sand, focus on the writers and their lives more than on their works. By contrast, the section on Madame Bovary is not really about Gustave Flaubert himself so much as it is a fascinating disquisition on translation per se, its insuperable compromises with perfection, and the fact that there is no such thing as a definitive version other than the original words.

Poetry can hardly be translated at all, which is one way to define it, but prose, too, especially dialogue, is also baffling. It can be rendered precisely in no language nor even at any time in history other than those in which it was written. Should a translator, to take one difficulty, render the imagery of the colloquial French in Flaubert’s great novel in precise English, sacrificing the verve of the vernacular? Or should he neglect precision and opt for equivalent colloquial English, capturing the energy of our argot but leaving the reader with only an approximate sense of what the original actually says?

Such stuff is dry as dust, perhaps even meaningless, to those uninterested and unpracticed in reading. But for people who still spend time with literature, Allen’s observations are permanently fresh, acute, and necessary. Her writing and her subject matter together evoke a small, exclusive literary world. They flatter the reader by dealing uncompromisingly with matters inaccessible to most people today. It is wrong to think of this as snobbery, as one critic on the back cover does. But it is a form of elitism — that form of which Harold Nicolson pleaded guilty, an elitism not of social class but of learning and culture.

Allen’s tone is elegiac, which is appropriate given that she is writing of an elevated world that is vanishing because few people today can any longer be bothered to pay attention to it. Books are often published not because they are well-written or have intrinsic merit, but at least partly because of extrinsic political or ideological factors, such as that the author is of an approved race or gender, or that their argument or narrative hews to some voguish agenda or advances some grievance mongering.

Reading Allen’s collection is an experience akin to being given one delightful little gift after another. It is chock full of sparkling literary anecdotes — one critic aptly described her work as “the most high-level, erudite gossip imaginable” — such as Shelley referring to James Henry Leigh Hunt dismissively as a “wren” compared to the “eagle” that was Byron. Richard Burton (the 20th-century actor, not the 19th-century adventurer) was, one discovers, an expressive, funny, and sometimes venomous diarist; he refers to Lucille Ball as Milady Balls and describes her as “a monster of staggering charmlessness.” To him, Lawrence Olivier is a “past master of professional artificiality … A mass of affectations.” Burton also describes doing bedtime exercises with his wife, Elizabeth Taylor, writing, “It is especially droll when we do running on the spot as she has to hold her breasts … It’s a very fetching sight and were it to be open to the public would fetch a lot of people. Like ten million.”

Allen does not just preserve but also rescues reputations. Of the poet John Betjeman, for example, she writes that the academic obsession with differentiating “major” poets from “minor” ones, deprecating the latter, serves no one and harms the public, which reads for pleasure rather than for careerist motives. She agrees with Edmund Blunden that the distinction between major and minor poets is especially unhelpful of Betjeman, who, like Dylan Thomas, was doubtless a minor poet, “but a very, very good one.” She discusses his sympathetic brilliance in delineating English social class distinctions, as shown in Betjeman’s poignant recollection of a children’s party in his poem “False Security”:

Can I forget my delight at the conjuring show?

And wasn’t I proud that I was the last to go?

Too overexcited and pleased with myself to know

That the words I hear my hostess employ

To a guest departing, would ever diminish my joy,

I WONDER WHERE JULIA FOUND THAT STRANGE

RATHER COMMON LITTLE BOY?

It is almost confounding to find some authors included as old bones. Can it be that “that old, old parrot,” Somerset Maugham, “with his flat black eyes, blinking and attentive, his courtly politeness and his hypnotic stammer,” will really disappear from view? Yes, sadly, it can, even though, in my 20s, my peers and I would have been embarrassed not to have read him. Allen, however, quotes Elspeth Huxley, wisely noting, “One of the surprises of advancing age is to discover that part of one’s lifetime has turned into history, a process which one generally assumes has come to a halt about the time one was born.”

Despite her mission to save her authors from oblivion, Allen is unsparing when she finds fault; Eudora Welty’s dialogue, she says, “is disgustingly folksy and conscious; none of the many voices can be differentiated from one another; the themes are obvious and uninteresting. Worse, the narrative has a smug confidence in the virtue of its own sentiments and values that neutralize the work’s integrity.” It is a good thing that Welty wrote other stories good enough to salvage the acclaim she is due.

HUGO GURDON: WORSE AND WORSE ON OBAMACARE

No matter how sharply Allen skewers her subjects and their works where necessary, however, she includes them because, with all their lapses, their work is important — important for being creative, attempting and sometimes achieving beauty and originality — and it will be a great loss to us all when it drops down the oubliette.

Allen’s collection of bones is a small treasure.

Hugo Gurdon (@hgurdon) is the editor-in-chief of the Washington Examiner.