When S.M. Arthur, an honorary fellow of the University of Cambridge, wakes up to the realisation that he’s dead, as he does in “Late,” one of five stories collected in Salman Rushdie’s The Eleventh Hour, he takes it rather well. True enough, having only just entered his seventh decade he “had not envisaged this turn of events,” in fact he “had been expecting several more years, twilight years, golden years, whatever people said these days,” with lots of things to do that ghosts don’t normally (or so I suppose) do: “meals to eat, galleries to visit, music to listen to, books to read,” and so on.

Still, being a ghost “at first didn’t seem to change anything,” or not for the worse, “in fact, he felt unusually healthy, well rested, and eager for the day.” Christian theologians have long wondered what kind of bodies people have in heaven: the old sacks they had when they died, or the spry bodies of their 20s, or perhaps (why not?) they’re forever 33, much like Christ himself. Arthur finds his ghostly body in much the same state as ever, except that the “side effects of his various medications had disappeared, the sluggishness he was used to was absent, his eyes felt good.”

It’s never been entirely clear to me why Rushdie is thought of as such a forbiddingly serious novelist, seeing as he is so often so very funny. The imbroglio S.M. Arthur finds himself in — that of the unenterprising chap trying to do the done thing even when plumped straight into confusing new circumstances — is the type of comic scenario of which Waugh and Wodehouse made whole careers. Befitting a Cambridge fellow, Arthur proceeds to grade the various philosophers who’ve tackled the mind-body problem. Descartes, he concludes, seems to have been on to something (“Guess what, René? Mostly right”) while “the old fellow Gautama’s idea turned out to be interesting.”

But how is a ghost to behave? Arthur is clearly facing a situation without precedents. As medical personnel carry away his physical body, Arthur gives it some thought: “It’s so strange, he told himself. All my life I was famous for my punctuality, even for showing up earlier than required, and now that time has slipped my grasp, I’m going to be — well, I am — forever Late. The Late S.M. Arthur.” That thought makes him chuckle, which he realizes mightn’t be quite proper for a ghost. “Control yourself, he thought. You’re a dead man. Dead men don’t have much to laugh about.”

Dignified comportment, then, is to be expected of English ghosts no less than of Englishmen in general. “He didn’t want to wander the grounds of the College in his blue pajamas. If he was a ‘ghost’ now, whatever that was, he did not want to become a laughingstock as well, a phantom in nightclothes.” And so, he grabs an “ectoplasmic variation” of his walking stick, pours into a pair of brown corduroy trousers and a tweed jacket, and floats to the nearest bar for a “half-pint of lemonade shandy.”

But what ought a ghost get up to? A game of croquet on the college green seems indicated, and with eternity to look forward to, he can potter about in the library and “maybe even come up with an original thought.” Ghost that he is, he eventually concludes that he should probably haunt his erstwhile tormentor, the college’s provost, Lord Emmemm. Delightful, really.

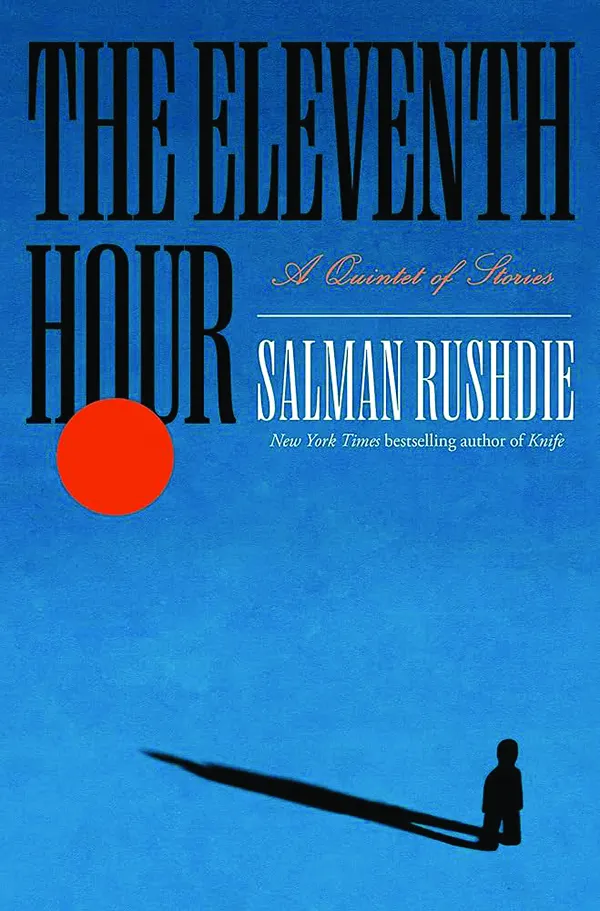

All five pieces in The Eleventh Hour offer reflections on mortality. As the narrator of the story “In the South” puts it, “If old age was thought of as an evening, they were well into the eleventh hour.” Age mellows most novelists, and Rushdie is himself past his 10 p.m. But if his prose style has mellowed slightly in some places, “The Musician of Kahani,” where the musical prodigy Chandni marries Majnoo, the needlessly handsome cricket-playing scion of the multibillionaire Ferdaus family, is full of Rushdie’s familiar themes (magical events), fixations (movie stars), and hysterical sentences (that forgo punctuation with words written in capitals) that suddenly end in something as pedestrian as a list. (“Hospitals, swimming pool, fancy shops, Sophia College, Art Deco buildings, Scandal Point, gardens, sea view.”)

The marriage between Majnoo and Chandni soon enough sours as the Ferdaus in-laws try to micromanage every part of her life while her own father leaves her to lead a life among the followers of cult-leader Shankar, who espouses the philosophy of “POMO,” not “postmodernism” but “The Possibilities of Mankind Movement,” which has as its guiding teaching something called “Free Sex Theory.” “‘Like Gandhiji,’ Shankar said, indicating the ladies. ‘I too am making my experiments with truth.’” Ensconced in Shankar’s compound, “Moon-on-Earth,” Chandni’s father ladles soup for the other followers whilst Shankar trousers their Rolexes.

In the meantime, the Ferdaus family pressures Chandni into pregnancy, which, for the sake of the “family brand,” must be celebrated in opulent style. “And the guest list!” the matriarch Dimmy Ferdaus exclaims to Chandni, “This time we are not only reaching for the top, not even the top-top, we are going so over the top it’s out of sight, baby doll. Royalty, honey pie, European et cetera, our own also obviously, but only the hottest young ones.” The party is to be held at the Taj (“No, not our beloved but overused grand hotel, darling… The Taj itself. Agra, baby.”), where they have escorts “on tap.”

With a celebration like that, everything must be timed to perfection, including the birth itself, so the Ferdaus prevail upon Chandni to have a “voluntary” caesarean section. Before it gets that far, however, the baby’s heart stops beating. Much like Arthur in “Late,” Chandni gets her supernatural revenge. She plays a magical sitar melody which brings ruin upon her enemies: calamity strikes Shankar when tax inspectors find his fleet of 93 Ferraris, the Ferdaus father is indicted for large-scale bribery, the mother succumbs to cancer, and Majnoo’s cricket career is ended when he takes a ball to the head.

This is where Rushdie flounders. He tries to hold it back, but his moralizing shoulders its way to the front. “The present decay of ethical society around the world is a matter of some concern. Words such as ‘good’ and ‘bad’ or ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ are losing their effect, emptying of meaning, and failing, anymore, to shape society,” he writes. “These are days in which ‘shamelessness’ is king.” The narrator of “The Old Man in the Piazza” puts it that, “We have ceased to be the poetry lovers we once were, the aficionados of ambiguity and devotees of doubt, and we have become bar-room moralists.”

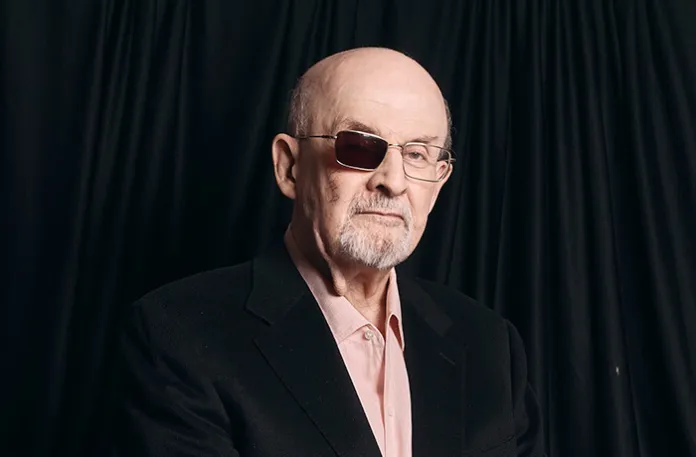

The seasoned reader of Rushdie should know to expect it. His satire had a barbed, not to mention hilarious, bite in his earlier novels — he took on Indira Gandhi’s Emergency in Midnight’s Children (1981), Pakistan’s leaden regime in Shame (1983), religious tradition in The Satanic Verses (1988), the Kashmir question in Shalimar the Clown (2005) — but by the time of Quichotte (2019), the electric current that ran through his early prose had gone. His targets were now those of the low-wattage bien pensant.

Too many easy “messages” litter the pages of the present collection. In “Late,” Lord Emmemm has forced Arthur into chemical castration in a way that rather too lazily resembles Alan Turing’s fate. “The Old Man in the Piazza” is one long lament that people have become overly sure of themselves, much along the lines of the sentence cited earlier. In the story “Oklahoma,” we find Goya seeking refuge from the court of that “totalitarian bastard” Fernando VII, who has changed language “to redescribe rape as love, horror as patriotism, bullying as good governance, war as peace, freedom as slavery, and ignorance as strength.” Here’s Rushdie, reduced to cribbing from a lesser novelist.

REVIEW: THE IMPERIAL W.H. AUDEN

In “The Musician of Kahani,” we’re told, “Let us try to dig a little deeper into this young man’s story, this Majnoo Ferdaus whose choices and actions would unleash such a tumult, such a disaster for all. Let us grapple with him sympathetically for the moment even though, as the story proceeds, it will become harder to feel sympathy for him.” It’s the George Eliot tick: Rushdie frets over moral shortcomings whilst congratulating himself on his capacity to show so much sympathy — the failure of sympathy, in other words, occurs precisely when it’s most loudly proclaimed.

Rushdie the bar-room moralist? Never.

Gustav Jönsson is a Swedish writer based in London.