After the Battle of Gettysburg ended, 43-year-old Basil Biggs, a prominent member of the black community in the once-thriving town, returned to his tenant farm to discover the cost of the largest battle of the war. Gettysburg’s prewar population was around 2,400, 8% of it black; within days, it had been swallowed by 165,000 soldiers. What remained of Biggs’s farmhouse was the remnants of a makeshift hospital: carpets, floors, and furniture soaked through with blood. Walking his land, he found his livestock slaughtered, crops destroyed, and 45 shallow graves of Confederate soldiers. On the first of the battle’s three days of horror, he had fled on a borrowed horse, along with most of Gettysburg’s black citizens, fearing enslavement at the hands of Robert E. Lee’s army. Their return revealed that even absence had not spared them: The battle had effectively destroyed him anyway.

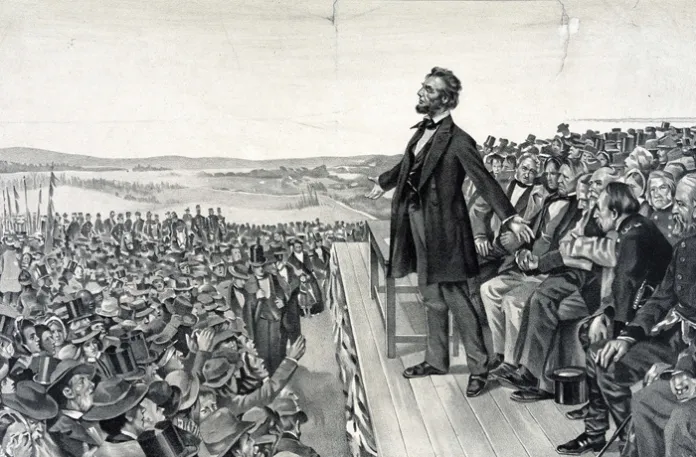

In recent decades, Gettysburg has come to be understood less as a military encounter than as an emancipatory turning point. It was not only the clash between the South’s greatest general and the North’s newly appointed commander, George Meade — elevated to lead the Army of the Potomac just three days before the fighting began — but also the site of consecration for the “new birth of freedom” Abraham Lincoln would famously proclaim in his address dedicating the ground months later. For while Ulysses S. Grant’s capture of Vicksburg the day after Gettysburg was arguably more strategically decisive, splitting the Confederacy and securing the Mississippi; while Shiloh was more psychologically shocking, awakening both sides to the industrial horrors to come; and while Antietam was more politically vital, giving Lincoln the opportunity to issue the Emancipation Proclamation — Gettysburg became something else. It became symbolic. More than a battlefield, it was recast as the foundation of a new America, born of sacrifice and moral clarity.

This unique significance — a convergence of roads as much as ideas — is the justification for Tim McGrath’s Three Roads to Gettysburg: Meade, Lee, Lincoln, and the Battle That Changed the War, the Speech That Changed the Nation. Rather than a conventional campaign history, McGrath offers a three-pronged biography, tracing the lives of two generals and a president toward a single moment. It is an ambitious structure, intended to mirror the battle’s claimed centrality not just to the war, but to the nation’s moral self-understanding.

If Gettysburg itself is often said to be greater than the sum of its parts, McGrath’s book, by contrast, is inevitably less. Given the scale of his ambition, it is neither the best biography of any of the three men nor the most compelling narrative of the battle itself. Each subject is necessarily condensed; little emerges that is new. And yet, ironically, the book’s very limitations illuminate something important. In attempting to stabilize Gettysburg’s meaning, McGrath instead exposes how unsettled it remains — how much “unfinished business” still clings to the battle and its legacy.

At the heart of this struggle is a deceptively simple question: Who is Gettysburg about? For decades, the answer was primarily Lee. Gettysburg was framed as the high-water mark of the Confederacy, the moment before hubris tipped into catastrophe with Pickett’s Charge on the third day. This romanticisation was captured memorably by William Faulkner, who wrote that “for every Southern boy” there is an eternal instant “when it’s still not yet two o’clock on that July afternoon in 1863,” defeat not yet inevitable and honour still intact. In such tellings, the battle’s significance as part of a struggle over slavery and the future of American democracy receded. Lee became the tragic hero: too brilliant, too beloved, too convinced of his army’s invincibility.

As Shelby Foote — Faulkner’s close friend and the author of perhaps the most evocative narrative account of the Gettysburg campaign in Stars in Their Courses — put it, the battle was “the price the South paid for Robert E. Lee.” In this formulation, Southern defeat becomes almost metaphysical and self-inflicted. Meade, by contrast, all but disappears: Lee defeats himself. The questionable nature of this was recognised even at the time. After the loss, General Pickett dryly remarked: “I’ve always thought the Yankees had something to do with it.” Meade himself, with characteristic fatalism, predicted his erasure in a letter to his wife: “I suppose after a while it will be discovered I was not at Gettysburg at all.”

McGrath seeks to redress this imbalance, but is only partially successful. He restores some agency and dignity to Meade, a man who had little national profile before the battle and whose star dimmed almost immediately after it — not least in the eyes of Lincoln, who blamed him, perhaps unfairly, for allowing Lee to escape. Where Meade does exist in the popular imagination, he is a prickly, methodical, uncharismatic engineer — a builder of lighthouses rather than legends. Yet, McGrath shows that he shared more with Lee than is usually acknowledged. Both were West Point men; both had seen combat in the Mexican War; both were effective engineers; both assumed their military careers were behind them before the war erupted; and both were capable of genuine compassion toward the men under their command.

Meade could also act decisively. General Francis A. Walker, then a lieutenant colonel, described Meade’s decision to send Winfield Scott Hancock to Gettysburg as “one of the boldest in the history of the war.” And while photographs of Meade as a gaunt, thinning-haired man in the autumn of his years, marked by a perpetually choleric disposition, contrast starkly with contemporary descriptions of Lee — “coat buttoned to the throat, sabre-belt buckled round the waist, and field glasses pending at his side” — we learn that as a young man Meade wore his hair long, in ringlets, like a cavalier, and was a gifted raconteur. The flattening of his image is itself part of the story McGrath is trying, imperfectly, to correct.

Yet, by including Lincoln as the third road — indeed, by beginning and ending with him — McGrath ultimately seeks to make Lincoln the book’s true protagonist. Gettysburg becomes less a military contest than a moral hinge: the moment at which the war’s meaning crystallised into a struggle over freedom itself. The battle, in this telling, imposes an enduring obligation — what McGrath calls the “opportunity and responsibility of living up to Lincoln’s challenge” — on each succeeding generation of Americans. This is where the book is least convincing. Whether because of the brute gravitational pull of Lee, the engrossing twists and turns of his decisions in the battle’s narrative, or the enduring power of the “Marble Man” image in American memory, Lincoln never quite dislodges him. Nor does the idea of Gettysburg as a great liberator survive close scrutiny — including McGrath’s own.

A telling anecdote toward the end crystallises the problem. After Basil Biggs returned to his ruined farm, it was the local black community that carried out the grim task of exhuming and reburying the dead from both sides. For four months, they dug up bodies, identified what they could by the fabric of uniforms — wool for Union, cotton for Confederate — and confronted the war’s physical residue. Then, in 1865, Biggs bought land on Cemetery Hill, the very ground Pickett’s Charge had targeted. When he began sawing down a grove of trees to build fences, the town historian rushed to stop him. These, he explained, were the trees Lee had pointed to as Pickett’s objective. They had survived the cannonade and should be saved. Biggs left them standing. His reaction was not recorded.

How should Biggs’s decision be read, especially when interpreting the battle through a moral lens? As an act of reconciliation? Of prudence? Of resignation? Or as evidence that Lee’s shadow still lay immovable across the battlefield, shaping not only its memory but its meaning long after the guns fell silent? For all its later sanctification, Gettysburg was not immediately understood as a moral turning point. For decades, it functioned as a site of Southern mourning and national ambiguity rather than emancipation. The idea of Gettysburg as the war’s redemptive moment is, in many ways, a retrospective construction — powerful, but reductive.

HOW THE CIVIL WAR BECAME INEVITABLE

McGrath ends by insisting that the future remains “in our hands.” Yet, the story he tells invites, in reality, more difficult questions. Whose hands have ever truly held Gettysburg’s meaning? And how much can be illuminated by viewing a battle of such scale and consequence through the lives of just three men, however significant?

Perhaps Gettysburg can only be approached by widening our focus: to the soldiers who fought in it; to the civilians who witnessed it; and to those for whom the battle was later said to have brought liberation, but who faced many more trials long after the guns fell silent. These experiences do not resolve neatly into a single narrative, moral or otherwise. The impulse to fit Gettysburg into one story — redemptive, tragic, or triumphant — risks doing precisely what history warns us against: mistaking commemoration for understanding.

Francis Dearnley is an executive editor at The Telegraph of London and one of the hosts of its award-winning war podcast Ukraine: The Latest.