In August 1944, while the renowned physicist Albert Einstein was living in comfort and safety in his adopted America, his first cousin Robert was hiding out in the woods in Nazi-occupied Italy. As a Jew and therefore a wanted man, Robert had agreed with his Italian wife, Nina, and their adult daughters, Luce and Cici, that his best means of evading capture was to leave their Tuscan villa, Il Forcado, and lie low in the surrounding countryside. The women would have no real cause for alarm if German troops came knocking. They were Christian and not on any hit list, and if asked where Robert was, they would simply say he was away. With news reports saying American and British ground forces were only 20 miles south of nearby Florence, the family was daring to believe their luck was changing: surely now the Germans were less likely to pay a visit and beat a retreat.

But events unfolded differently. Early in the morning of Aug. 3, it was not the Allies but rather a heavily armed unit of German soldiers that turned up at the villa. What’s more, they did not come knocking. Instead, they smashed open the front doors. The German captain announced they had orders to arrest Robert. When Nina professed ignorance as to her husband’s whereabouts, she was locked in the cellar with her daughters, her sister, and three of her nieces. After enduring hours of panic and uncertainty, Nina, Luce, and Cici were separated from the other women and questioned again, this time more fiercely. Eventually, the Nazis’ patience ran out. They machine-gunned the three women, then set the house on fire.

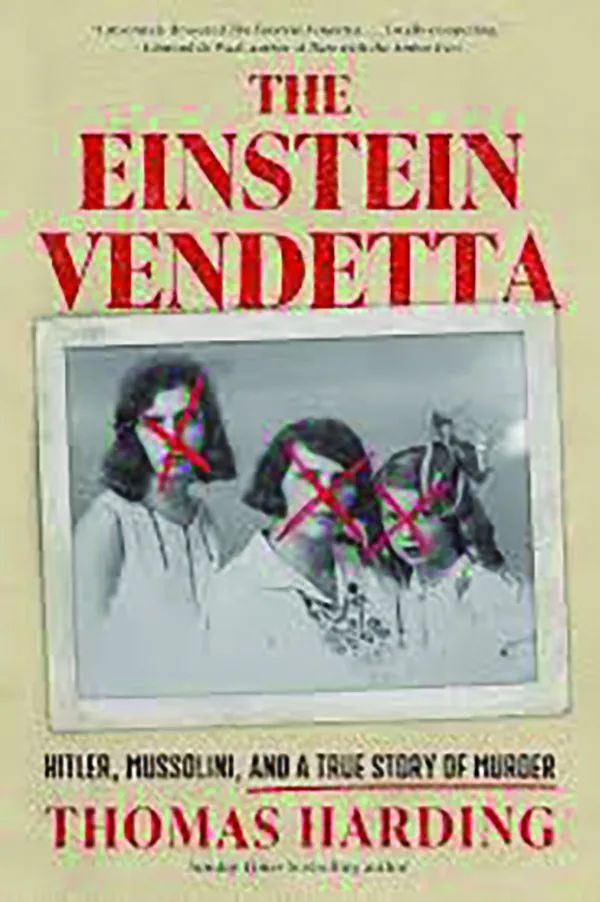

This wartime atrocity and the long, cold shadow cast by it form the subject of Thomas Harding’s latest book. The Einstein Vendetta snares us with its opening depiction of an agonizing ordeal that culminated in brutal triple murder. It later branches out to chart various individuals’ investigations into tracking down the perpetrators of the crime, in a bid to seek justice and solve a decades-old mystery.

Harding takes a calculated risk in his first section by splicing together two narrative strands. Chapters relaying the tragic plight and last hours of the three women alternate with the broader backstory of Robert’s origins. A lesser writer toggling back and forth in this way might frustrate his reader. However, Harding maintains momentum and keeps us invested. He describes how Robert forged a close bond with Albert (“some might call them brother-cousins”) while growing up in the same house in Munich in the 1880s and 1890s. After a move to northern Italy, Robert followed in his father’s footsteps and studied to become an electrical engineer. He met and married Nina in Rome, then relocated to Germany with his new wife.

But then World War I broke out, shattering all prospects of domestic calm. Robert enlisted and fought on the Western Front, much to the chagrin of Albert, who was by then a Swiss citizen who had long since divested himself of any semblance of German patriotism. As Albert wrote to his sister, “He was not as careful as I was in choosing his fatherland.”

Robert chose his fatherland again at the end of hostilities, when he and Nina decided to return to Italy and, in time, buy Il Forcado. But their rural idyll was threatened and then their lives destroyed by aggressors with warped notions about fatherland, fantastical ideas concerning race, and the dogmatic belief that they could act without mercy toward anyone who stood in their way.

Harding’s second section, which details the aftermath of the murders, is compellingly bleak. Broken by grief and guilt, Robert came out of hiding and went in search of trigger-happy Germans. Finding none, a partisan fighter and a priest had to talk him out of committing suicide. He soldiered on until July 1945; then, almost a year on from the loss of his nearest and dearest, he took a fatal overdose of sleeping tablets. “Thus ended the drama of that family, totally annihilated by Nazi ferocity,” a priest declared.

Not that Harding ends the drama there. It is at this juncture that he widens his focus to both chronicle the hunt for the killers over the years and examine the attendant complexities of the case. In doing so, he elevates what would otherwise have been a straightforward tragic tale into a riveting quest for the truth.

Harding shines a spotlight on a range of investigators and their dogged detective work. He begins in 1944, six weeks after the murders, with Maj. Milton Wexler of the newly formed U.S. Fifth Army War Crimes Commission. Wexler visited the crime scene and conducted interviews with the surviving family members, who told him that they believed the murders were not random, spontaneous killings but a targeted, premeditated hit job. If the Nazi regime could not assassinate Albert, one of its most loathed enemies, then it would take out its wrath on his close relative. And if Robert could not be eliminated, then his wife and children would suffice.

Harding brings in other investigators who grappled with the case in the 21st century: in Germany, a judge, a journalist, and a public prosecutor; in Italy, a historian and the country’s most famous Nazi hunter; and in Canada, an expert in fingerprint analysis. TV shows, online photographs, and fresh trawls through dusty archives produced new leads. Three German men emerged as plausible candidates for the captain who issued the command to kill Robert’s family. But which one was the culprit? And, after so many years, what measures can be taken to prove his guilt?

The Einstein Vendetta is a work of meticulous research. Harding drew on investigative reports, official records, and written testimonies. He also managed to speak with several eyewitnesses, some of whom are now nonagenarians. At the outset, in his author’s note, he explains that his book is an attempt to “reach for the complete truth.” It is no great spoiler to reveal he does not fully achieve this — too much time has passed and too many key players are dead — although it is not for lack of trying. Where hard facts are not available, Harding, for the most part, convinces with strong theories. Unfortunately, though, he is unable to prove conclusively that Hitler initiated the kill order or that the murders were carried out because of a vendetta.

This may render Harding’s title something of a misnomer, but it does not detract from the overall quality of his book. His account of how an elegant villa became a house of horrors is a queasily gripping piece of narrative nonfiction. Illuminating tangential passages provide context on Italian topics such as the rise of fascism, Jewish persecution, and what Harding calls “the myth of the Good Italians,” which was perpetuated in the postwar years when the country was in denial about, and trying to move on from, its alliance with Nazi Germany.

Best of all is the book’s final section, which exerts a thriller-like grip. Harding’s treatment of the investigations comprises open and closed cases, possible suspects and unreliable witnesses, fact-finding trips far and wide, and a momentous discovery in a secret cupboard — one an Italian journalist dubbed the “Wardrobe of Shame.” Harding introduces this part with a quote from Albert: “The important thing is not to stop questioning.” Harding’s rigorous questioning might not always yield answers, but it does give his propulsive study satisfying heft.

Malcolm Forbes has written for the Economist, the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post. He lives in Edinburgh.