Earlier this month, President Donald Trump issued a pardon for Adriana Camberos, a businesswoman who had been convicted of fraud in 2024.

Amid the thousands of pardons the president has granted during his current term, which have encompassed Jan. 6 rioters, cryptocurrency kingpins, a former Puerto Rico governor, and even a former Honduran president, this one stood out: Trump had already commuted the sentence imposed on Camberos for a similar offense four years earlier, but she returned to her fraudulent ways and found herself in prison a second time. And for a second time, according to the New York Times, Camberos enlisted the help of two attorneys who had previously served in the Trump administration, including one who had represented Rudy Giuliani.

Trump has taken pardon abuse to staggering new heights, issuing various forms of clemency at least an order of magnitude more frequently than any of his predecessors. But former President Joe Biden also granted several deeply problematic pardons, and presidents over the course of recent history have been no strangers to the practice. It used to be the case that presidents would sheepishly announce the bulk of their clemency decisions during their final months in office as lame ducks, but the second Trump administration has proudly and consistently been handing them out throughout his first year in office.

So what on Earth is going on? How and why have clemency grants spiraled so far out of control? And, given the pardon clause’s seemingly unassailable place in the Constitution, can the genie possibly be put back into the bottle?

I would humbly submit that we can and must take action to rein in a presidential privilege that has fundamentally transcended its original bounds. In a superb new book, University of Virginia law professor Saikrishna Prakash explores the evolution of the pardon power and offers suggestions on how to rationalize it. “As presidents wield the pardon pen,” Prakash writes, “they advance their ideological and personal agendas, bolster their electoral bases, inflict psychic wounds on opponents, and wreak havoc upon the rule of law.”

Yet we needn’t proceed down this path. As Prakash puts it, “Considerable good also could arise from a different pardon regime.” He urges us to “reform the pardon power in a way that generates far less heat and far more acclaim.”

It will surely be an uphill battle, but, to borrow a phrase from elsewhere in the Constitution, it’s a necessary and proper one — that is, if we want to restore balance to our liberal order.

But we must start by examining how we got here in the first place.

Origin story

The practice of a sovereign issuing clemency to his subjects dates back to the Bible, Ancient Mesopotamia, and probably earlier, but the peculiarly American version of the pardon power derives directly from our British ancestors. As Prakash puts it, the pardon clause is “a regal remnant that, in some respects, renders the president more powerful than the British monarch of the eighteenth century.”

At common law, the British tradition of clemency anchored itself in mercy, reconciliation, and law enforcement: By providing leniency to some, the king ensures compliance by most. Specifically, Prakash finds, pardons helped “secure soldiers, exile miscreants, and fill the Crown’s coffers,” at least in cases where clemency recipients paid a fee for the privilege. They also greased the skids for parliamentary appropriations and for the king’s favored courtiers, who, “in exchange for their access and influence … charged hefty fees to would-be pardon-seekers.”

The colonies swiftly adopted their forebears’ customs. New York, Maryland, North Carolina, and Delaware granted their governors the exclusive power to pardon, while New Hampshire, Virginia, Vermont, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and New Jersey required the participation of the legislature. The principal justifications for the practice during the Revolutionary Era included rehabilitating loyalists and integrating them into the new country. Gen. George Washington set the tone, sometimes approving a death sentence, allowing a noose to be placed around the condemned’s neck, and only then granting a reprieve.

But as the constitutional conventions gathered steam, a heated debate erupted over the proposed language for a federal pardon authority, namely, that the president “shall have the power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.” The Anti-Federalists objected vigorously, arguing that the clause awarded the president “absolute power” and “unrestrained power,” insisting that this “unlimited” prerogative be confined by “proper restrictions.” George Mason refused to sign the Constitution in part because of the pardon power, while a North Carolinian delegate feared the president might spearhead “a combination against the rights of the people, and may reprieve or pardon” his clique, thus rendering the clemency “perverted to a different [sinister] purpose.”

Others disagreed. Alexander Hamilton generally favored the “benign” power because the criminal code “partakes so much of necessary severity, that without an easy access to exceptions … justice would wear a countenance too sanguinary and cruel.” At the same time, Hamilton allowed that “there are strong reasons to be assigned for requiring the concurrence of [the legislative] body” in certain instances. The debate raged for months, and Prakash suggests that “had states voted clause by clause, some of them might have spurned the Pardon Clause.” But the Constitution, of course, was ratified in its totality.

A brief history of presidential pardons

Presidents Washington, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson all exercised their constitutional clemency authority, which included a multiplicity of forms springing from the Constitution’s single sentence. Reprieves are delays of a judicial sentence in the interest of justice. Full pardons wipe the slate clean entirely. Commutations reduce punishment — lucky Ms. Camberos has the unique distinction of receiving both a commutation and a pardon. Remissions diminish or eliminate financial penalties. Amnesties pardon groups. Preemptive pardons precede conviction: Blanket pardons forgive all offenses, while conditional ones depend on certain contingencies.

One charming example from our first president:

“Whereas the said Joseph Hood hath by his petition to me set forth that he has already sustained an imprisonment of many months before his trial and hath an aged mother to maintain, and the character and conduct of the said Joseph Hood is certified to be otherwise fair and honest, and the said Joseph Hood by his said petition hath besought a remission of so much of the said Judgment of the Court as subjects him to further imprisonment. Therefore, I George Washington, President of the United States, in consideration of the premises herein before set forth have thought proper and by these presents do grant unto the said Joseph Hood a full, free and entire pardon of the said offence whereof he so stands convicted.”

Washington, in particular, employed a deliberate and methodical manner of evaluating pardon requests, consulting with Cabinet members, trusted counselors, and even the chief justice of the Supreme Court. He granted the first amnesty to most of the participants in the Whiskey Rebellion in western Pennsylvania in the 1790s. Along similar lines, Hamilton opined that “in seasons of insurrection or rebellion, there are often critical moment, when a well-timed offer of pardon to the insurgents or rebels may restore the tranquility of the commonwealth.” Overall, Prakash reckons that Washington employed a “measured, cautious, thorough, inquisitive” approach to considering clemency.

His successor, Adams, pardoned another set of Pennsylvania tax rebels days before their execution in 1798, prompting accusations from Jefferson’s camp that he was courting favor in a swing state ahead of an election. If so, it failed, and Jefferson pardoned the journalist James Callender, who’d been convicted under Adams’s Sedition Act. This, too, prompted allegations of partisanship, as Callender had lambasted the Federalist Adams and exposed Hamilton’s extramarital affair. These parochial pardons would echo down to contemporary times. “In the years and decades to come, would every president leaving the Oval Office issue a flurry of pardons to allies?” Prakash wonders. “A rabid, partisan official who expected a pardon at the end of a president’s term might be steeled to purpose, pursuing enemies and presidential agendas with extra zeal, knowing that forgiveness would come soon.”

Skip ahead two generations to 1863, when President Abraham Lincoln issued a blanket amnesty to Confederate soldiers and civilian officials, provided they swore an out to “abide by and faithfully support all acts of Congress passed during the existing rebellion with reference to slaves, so long and so far as not repealed, modified, or held void by congress, or by decision of the Supreme Court,” as well as the corresponding presidential proclamations. This balance between rehabilitation and contrition broadly satisfied most people, but Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, a Tennessee Democrat more sympathetic to the South, removed many of the guardrails Honest Abe had erected. Johnson’s opponents grumbled that his indulgence empowered Southern recalcitrance and stifled Reconstruction.

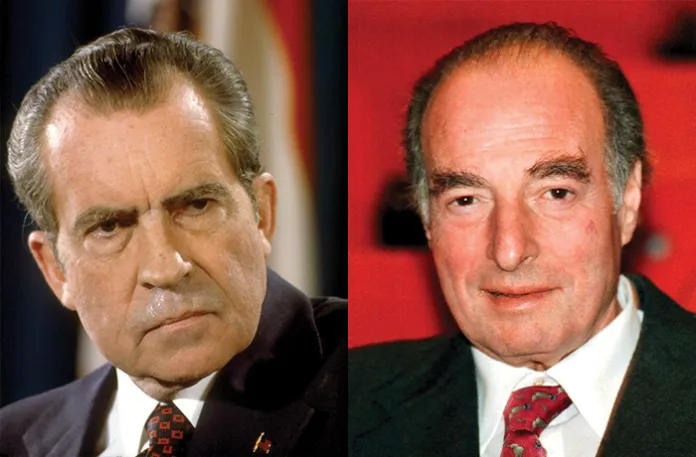

Far more controversially, a century later, President Gerald Ford pardoned his own predecessor after Richard Nixon resigned over the Watergate scandal. Ford sought “domestic tranquility” and reckoned that a trial would “cause prolonged and divisive debate over the propriety of exposing to further punishment and degradation a man who has already paid the unprecedented penalty of relinquishing the highest elective office of the United States.” But Democratic critics pounced, with Minnesota Sen. Walter Mondale lamenting that the pardon meant “we may never know the full dimensions of Mr. Nixon’s complicity in the worst political scandal in American history.”

Pardon disputes would haunt Presidents George H.W. Bush, who issued clemency to former Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger and others implicated in the Iran-Contra scandal, and Bill Clinton, who pardoned 16 Puerto Rican terrorists, his half-brother, his former business partners, and a tax-outlaw financier named Marc Rich, whose ex-wife had donated generously to the Democratic Party, the Clinton Presidential Library, and Hillary Clinton’s Senate campaign. But following a quarter-century of relevant quiet, a storm was unleashed.

The inexcusable Biden and Trump pardons

“If entropy is an iron law of physics,” Prakash writes, “then corruption is an iron law of politics. All political institutions tend toward corruption, with awesome powers given for noble purposes perverted to promote the narrow interests of officials.” At no time was this truer than on Jan. 19 and 20, 2025, when outgoing President Biden and incoming President Trump issued a raft of deeply problematic clemency orders, which Prakash characterizes as “grounded in partisan considerations, most prominently a profound distrust of the opposing administration.”

Biden kicked things off in December 2024, when he pardoned his son Hunter Biden unconditionally for any and all “offenses against the United States which he has committed or may have committed or taken part in during the period from January 1, 2014 through December 1, 2024.” Hunter Biden had been convicted of gun crimes and had pleaded guilty to nine tax charges. During the presidential campaign, his father had pledged to “abide by the jury decision” and vowed not to pardon him. But a month after losing the election to Trump, Biden reversed himself, bemoaning that “my family has been subjected to unrelenting attacks and threats, motivated solely by a desire to hurt me.” The day before he left office, Biden added insult to injury by issuing blanket preemptive pardons for his two brothers, his sister, and their spouses.

Trump, as is his wont, one-upped his predecessor the next day, granting a blanket amnesty to the participants in the Jan. 6 Capitol riot. Like Biden, Trump broke a campaign promise not to pardon everyone. Days before the inauguration, then-Vice President-Elect JD Vance insisted that “if you protested peacefully on Jan. 6 and had Merrick Garland’s Department of Justice treat you like a gang member, you should be pardoned. If you committed violence on that day, obviously you shouldn’t be pardoned.” But Trump granted “a full, complete and unconditional pardon to all other individuals convicted of offenses related to events that occurred at or near the United States Capitol on January 6, 2021.”

Amid the celebrations, even the new president’s Republican allies were dismayed. “Pardoning the people who went into the Capitol and beat up a police officer violently, I think, was a mistake, because it seems to suggest that’s an OK thing to do,” Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) cautioned. Sen. Thom Tillis (R-NC) found it “surprising to me that it was a blanket pardon” and said, “I just can’t agree.” In general, the pardons both reflected and bred distrust of the American criminal justice system. “Biden and Trump were sending the same message,” a former U.S. attorney told PBS NewsHour. “Trump was saying it was a corrupt system the last four years, and Biden was saying it’s about to be a corrupt system. And that’s a horrible message.”

Since then, things seem only to have gotten worse. In March 2025, Trump pardoned Trevor Milton, an electric vehicle entrepreneur convicted of fraud and ordered to pay hundreds of millions in restitution, five months after Milton and his wife had donated $1.8 million to Trump’s campaign. In October, the president issued clemency to Changpeng Zhao, the founder of the cryptocurrency exchange Binance, who’d been convicted of money laundering and whose company became entangled with World Liberty Financial, a crypto firm linked to the Trump family. Numerous others have followed, leading critics to suggest a “cash for clemency” operation in full bloom.

But money represents only one way that the pardon power has become corrupted. As Prakash writes, “Much as Carl von Clausewitz said of war, pardons have become the continuation of politics by other means.” In this case, both Biden and Trump misused their clemency authority in furtherance of certain policy goals. In 2022, Biden issued a blanket amnesty for anyone convicted or accused of marijuana possession, and, two years later, commuted almost all prisoners on death row, stating at the time that “America must stop the use of the death penalty at the federal level” except in very rare cases. By using the pardon power to undermine congressional statutes, Biden once again embarked on a new and dangerous constitutional journey. Prakash frets, rightly, that these “policy pardons” will open the door to a future president amnestying all illegal immigrants or tax evaders and come perilously close to an outright, and unconstitutional, suspension of law.

Given this parade of horrors, what should we do now? Can this breach be repaired, and, if so, how?

How we fix it

It’s worth noting at the outset that no separation of powers or checks and balances apply to the pardon power. “The constitution,” Prakash observes, “does not impose many limits, and, according to established judicial doctrine, Congress cannot impose any additional ones.” Thus, from the get-go, our options to mend the pardon clause are limited.

But limited doesn’t mean nonexistent, and there are several paths forward, however narrow they may be.

First, the legislative branch must insist that the executive follow appropriate procedures in granting clemency. In 1894, in an effort to rationalize the process, Congress established the Office of the Pardon Attorney within the Justice Department. Under these guidelines, generally speaking, the pardon attorney considers five factors: “post-conviction conduct, character, and reputation”; the “seriousness and relative recentness of the offense”; “acceptance of responsibility, remorse, and atonement”; the “need for relief”; and “official recommendations and reports.” In the case of commutations, the pardon attorney considers the “disparity or undue severity of sentence, critical illness or old age, and meritorious service rendered to the government,” including cooperation with investigators.

There’s no good reason why Congress can’t insist that the pardon attorney do its job and issue public, written justifications for every act of clemency undertaken by the White House. Perhaps these justifications will be self-serving, perhaps they’ll be incoherent, but the administration should, at a minimum, be forced to go on record to defend its decisions.

Second, the president should expand the circle of pardon reviewers and deciders to other trusted advisers, including the Cabinet, select members of Congress, and other professionals within the pardon attorney’s office. The chief executive could still retain ultimate authority to render clemency decisions, but his proclamations would have the input and guidance of a wider, possibly bipartisan and multibranch set of counselors. As Prakash argues, “The more people or institutions that can grant pardons, the more mercy, calibration, and reconciliation we will see.”

Unfortunately, Congress’s ability to constrain the White House is limited. Appropriately enough, in the 2024 Trump v. United States case, the Supreme Court held, relying on a ruling from 1870, that “the President’s authority to pardon … is ‘conclusive and preclusive,’ ‘disabling the Congress from acting upon the subject.’” Still, even without formal power to compel change, Congress and the people at large can employ moral and political suasion to demand better behavior by the White House.

Finally, in a worst-case scenario, a constitutional amendment restricting the president’s exclusive pardon authority may be necessary. Just as certain colonies required legislative acquiescence to pardons, a fed-up public could decide to require Congress’s input into executive clemency orders. Alternatively, an amendment could restrict the types of crimes for which pardons and commutations are available, excluding, say, treason or murder, or barring presidential family members from receiving clemency. While mustering the support of two-thirds of Congress and three-quarters of state legislatures would be a tall order indeed, especially with both parties reluctant to unilaterally disarm, pushing the amendment’s effective date out by several terms would lessen the blow.

In the end, we can surely pull back from the brink. As Prakash concludes, “We must either make our peace with our clemency dystopia or push for pardon reform, perhaps even constitutional amendments. If our presidents have shifted from faithful law enforcers to political creatures moved by personal or partisan motives, we must reconsider and reform how America dispenses mercy.” Amen to that.

Michael M. Rosen is an attorney and writer in Israel, a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, and the author of Like Silicon From Clay: What Ancient Jewish Wisdom Can Teach Us About AI.