I recently walked into my politics class at Sarah Lawrence College prepared to discuss civic protest. The prompt was Minneapolis, where a recent immigration enforcement surge has sparked mass demonstrations, a general strike, and the fatal shooting of two civilians by federal agents.

I planned to cover basic principles: the right to protest, the obligation to remain nonviolent, the distinction between civil disobedience and coercion. My students rejected the premise almost immediately.

“What are we supposed to do?” one asked. “Hold signs while people are being shot?”

“You’re asking us to play by rules that only we follow,” another said.

They cited the Black Panthers. They invoked Stonewall. They argued, confidently, that throughout American history, violence or the credible threat of it was what forced change. Several endorsed armed confrontation with Immigration and Customs Enforcement as both effective and ethically justified.

This view dominated the discussion.

I have spent 20 years studying these attitudes in survey data. But numbers do not argue back. What I encountered that day around the seminar table was the data made flesh: Students who spoke about political violence not with reluctance or regret, but with moral certainty.

Where did they learn this? Twenty years ago, I would have said: Not from mainstream American politics.

In 2005, my co-authors and I published Culture War? The Myth of a Polarized America, drawing on extensive polling data to make a simple claim: Despite the heat generated by political elites and cable news, ordinary Americans were not deeply polarized. They were broadly moderate, tolerant, and pragmatic. The supposed culture war was real among activists, donors, and other political elites, but most citizens stood apart from it, often confused, politically disengaged, and largely uninterested.

That argument remains true in one crucial sense: America’s center has not radicalized — it has checked out. But something else has changed. The rhetoric of delegitimation and deep affective polarization that once floated above ordinary Americans, confined to cable news and activist circles, is now being absorbed by their children.

Consider what my students are hearing from elected officials.

Last month, Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner issued a statement that would have been unthinkable from a major American law-enforcement official a generation ago. Speaking about federal immigration agents, Krasner declared: “In a country of 350 million, we outnumber them. If we have to hunt you down the way they hunted down Nazis for decades, we will find your identities. We will find you. We will achieve justice.”

This was not a call for lawful accountability, but a threat of extrajudicial pursuit with language more suited to revolutionary tribunals than a constitutional republic. His sheriff followed with a blunt endorsement: “You don’t want this smoke.”

These were not rhetorical slips uttered in haste. Krasner chose his words deliberately. He did not call for investigation, prosecution, or judicial review. He invoked the language of collective pursuit and moral retribution, explicitly likening federal officers enforcing U.S. law to Nazi war criminals.

That comparison is not merely offensive. It is profoundly un-American.

This was not fringe rhetoric shouted from a street corner. It came from elected officials in a major American city charged with enforcing the law. And it was cheered by many.

The language matters. Krasner did not promise accountability within constitutional bounds. He promised pursuit. Not the rule of law, but moral vengeance. He framed government agents not as public servants subject to restraint and due process, but as enemies to be exposed and hunted.

My students are watching. And they are drawing conclusions.

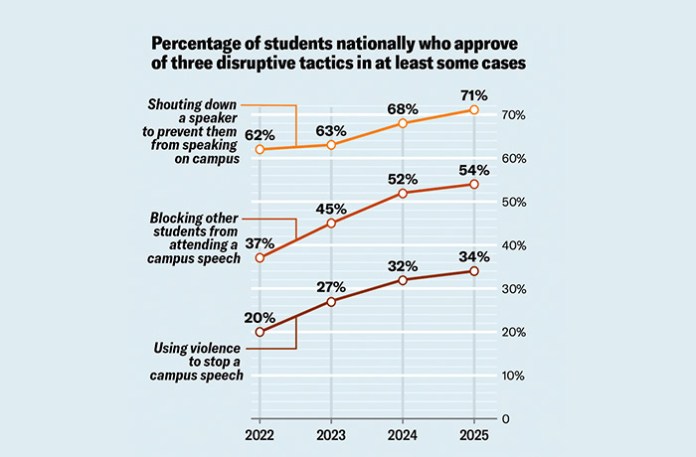

The survey data confirm that what I saw in my classroom is not an isolated case. Over one-third of students now say using violence to stop a campus speaker is acceptable. Nineteen percent of adults under 30 believe political violence is sometimes justified, compared with just 3% of those 65 and older. Republican and Democratic students increasingly converge in their willingness to excuse force, even as they target different opponents. It is a generational shift.

The centrist middle has not radicalized, as Gallup numbers confirm what I argued two decades ago. In 2025, 45% of Americans identified as political independents, the highest share ever recorded, while Democrats and Republicans each claimed just 27%. Independents remain disproportionately centrist. What has collapsed is not moderation, but attachment. The center has not migrated to the extremes. It has exited the arena altogether.

But while the center checked out, the elites kept talking. And a generation grew up listening.

What I am describing is the erosion of a foundational American norm: The belief that political opponents, however wrong they may be, remain legitimate participants in a shared civic order, and that conflict must be governed by law rather than resolved through intimidation or violence.

What we are witnessing is not ideological polarization so much as affective polarization, the transformation of political disagreement into moral hatred in which opponents are no longer seen as mistaken fellow citizens but as illegitimate and dangerous enemies. When that norm collapses, politics does not become more just, it becomes more primitive.

Participation in contemporary political institutions increasingly demands ideological signaling, tolerance for escalation, and comfort with moral absolutism. The costs of engagement rise while the rewards for restraint diminish. Over time, institutions cease to reflect the public at large and instead reward the most intense and uncompromising participants.

When moderates disengage, the committed inherit the institution.

This is not abstract. In Philadelphia’s 2025 primary, the one that gave Krasner a third term, turnout was just 15%. A small activist cohort selected officials empowered him to speak in the name of the city. The same pattern now repeats across school boards, city councils, party committees, and faculty senates nationwide.

Intensity is mistaken for mandate. Activism is mistaken for consensus. And the rhetoric that fills the void is teaching a generation that opponents are not fellow citizens to be persuaded, but enemies to be defeated.

What my students did not recognize and what many political actors now seem to have forgotten is that America was never founded on consensus. It was founded on the management of disagreement.

The Revolution itself unfolded amid deep internal division. Families split. Neighbors turned on neighbors. Loyalists were harassed, dispossessed, and exiled. The Founders did not emerge believing unity was natural. They emerged believing conflict was permanent.

The Constitution was built for that reality. It did not assume that citizens could always persuade one another, or even that they trusted one another. It assumed the opposite. Its purpose was to contain conflict, to prevent disagreement from hardening into violence.

Separation of powers, checks and balances, federalism, and slow deliberation were safeguards designed to make self-government possible even when persuasion failed. The American experiment was never a bet on harmony. It was a bet on restraint.

What has changed in recent years is not the existence of division, but the growing belief, especially among the young, that moral certainty licenses coercion and precarious action. That opponents are not merely wrong, but dangerous, illegitimate, and undeserving of protection.

There is a tradition of confrontational activism in American life that did not cross that line. But my students barely know it.

Another Larry, Larry Kramer, understood it. When Kramer founded ACT UP during the AIDS crisis, he rejected polite appeals to a government that had abandoned a dying population. ACT UP disrupted the FDA, blocked traffic, and courted arrest. The confrontations were aggressive and theatrical. They were also nonviolent.

That discipline was not incidental. It was the source of the movement’s moral authority. ACT UP’s power rested on the asymmetry of vulnerable citizens demanding recognition from an indifferent state. Kramer used incendiary rhetoric but understood that legitimacy would collapse the moment force entered the picture.

ACT UP forced attention without licensing retaliation. That distinction is why it changed policy rather than hardening opposition.

What we are seeing now is different.

In Philadelphia, Krasner borrows the aesthetics of moral urgency while discarding the restraints that once made such movements legitimate. He speaks the language of justice while encouraging the logic of faction, dividing the world into the righteous and the condemned. Both Larrys invoked Nazis. Only Kramer understood that the comparison obligates nonviolence, not vengeance.

My students see the confrontation and miss the constraint. They draw the lesson that escalation, not restraint, is what gives politics meaning.

When politics becomes a moral emergency, restraint looks like complicity. Law looks like obstruction. Violence begins to feel justified rather than tragic.

None of this excuses federal misconduct. Enforcement actions, deaths involving federal agents, and resistance to investigation deserve scrutiny. These realities help explain why incendiary rhetoric resonates. But explanation is not justification.

Assaults on ICE officers have risen sharply. Agents operate in cities where elected officials speak openly about pursuit and retribution. Decisions are made in environments thick with fear and reciprocal escalation.

If political violence concerns us, and it should, then it must concern us consistently. Violence against immigrants is unconscionable. Violence against federal officers is also unconscionable. A moral framework that excuses one while condemning the other is not principled. It is factional.

Accountability is not vengeance. The rule of law is not a weapon to be wielded only against one’s enemies.

American social movements have involved confrontation. But they succeeded when they preserved moral asymmetry, when they exposed injustice without abandoning restraint. When movements surrender that restraint, they trade legitimacy for power, and power for escalation.

That is not reform. It is the logic of faction. And as the United States approaches its 250th anniversary, this is the story we need to tell honestly.

America was never founded on unity. It was founded on a far more demanding proposition: Deep disagreement could exist without violence. The Founders did not expect citizens to persuade one another. They expected them to restrain themselves.

The Constitution was designed to make that restraint possible even when passions ran hot and trust ran thin. Self-government, in this view, was not expressive or therapeutic. It was procedural. It depended on legitimacy, limits, and the refusal to treat political opponents as enemies.

What is new in our moment is not disagreement, but the normalization of moral delegitimation: the belief that opponents are not merely wrong, but evil, and therefore undeserving of restraint. That belief has long existed among political elites. What has changed is that a generation is now growing up believing it too.

TRAGEDY IS NOT A TEMPLATE FOR MASCULINITY

At 250, the question before us is not whether Americans will disagree. We always have. The question is whether we still believe disagreement must be governed by constitutional rules even when persuasion fails, or whether we are prepared to let moral certainty license harm.

The American experiment has survived extraordinary division before. It will not survive politics without restraint.

Samuel J. Abrams is a professor of politics at Sarah Lawrence College and a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.