“If the most solemnly and democratically adopted text of the Constitution and its Amendments can be ignored on the basis of current values,” Justice Antonin Scalia wondered during a 1988 speech in Cincinnati that would later form a law review article entitled “Originalism: The Lesser Evil,” then “what possible basis could there be for enforced adherence to a legal decision of the Supreme Court?” This take-no-prisoners approach to the Constitution characterized Scalia’s uncompromising commitment to the truth: discerning and applying to modern circumstances the original public meaning of our founding document.

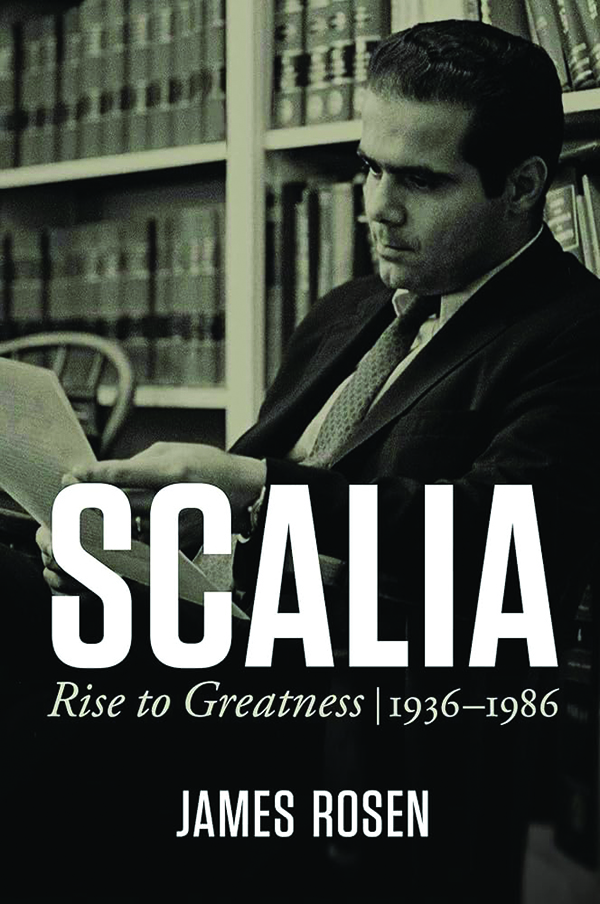

Scalia’s lifelong quest for truth — including the many benefits it conferred on the American legal and political culture and the sometimes heavy costs it exacted from the justice himself — forms the core of Scalia: Supreme Court Years, 1986-2001, the second volume in James Rosen’s masterly tripartite biography of the justice. A veteran journalist, Rosen (no relation) combs internal court correspondence, archival files, journals, and media reports and harnesses them into a vivid and lively portrait of a jurist at the height of his powers.

His second volume picks up where the last one left off: with its subject’s nomination to the highest court in the land. The product of over 100 interviews with family members, fellow justices, law clerks, close friends, and many others, Supreme Court Years spans the first half of the 30-year Court tenure of the man known to his intimates as Nino, and renders highly complex legal and constitutional debates into pleasantly readable and even, at times, propulsive prose.

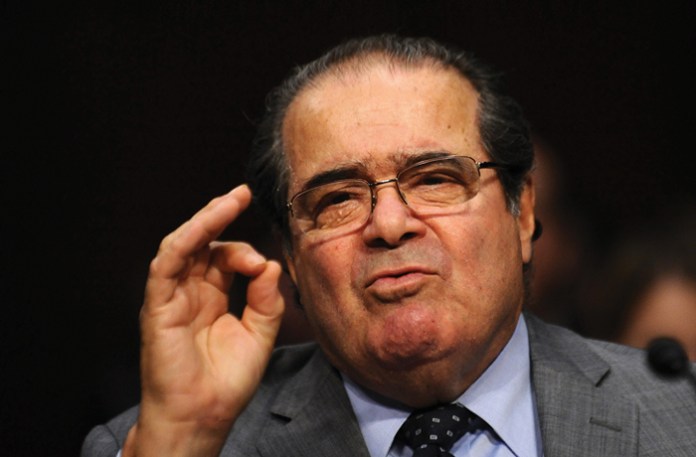

During his confirmation process, Scalia famously told Joe Biden, then a senator and the ranking member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, that the Constitution is “intended to be an insulation against the current times, against the passions of the moment that may cause individual liberties to be disregarded, and it has served that function valuably very often. So I would never use the phrase ‘living Constitution.’” He won confirmation by a 98-0 vote.

In those early years, Scalia’s colleagues effused over his intellect and temperament. “We’ve met. He’s delightful,” said Justice William Brennan, a liberal lion. “If what [Scalia’s appellate colleagues] say about him is true, he will be great fun to have as a colleague.” Justice Sandra Day O’Connor noted in her journal that “Nino Scalia will have a dramatic impact here. He is brilliant, confident, skillful, and charming.” Scalia would return the favor, warmly embracing Clarence Thomas after he’d triumphed in a brutal confirmation battle and befriending Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, with whom he would forge an unlikely partnership.

But Scalia cared little for such blandishments, focusing instead on developing an originalist jurisprudence not then in good standing among the paladins of the law. The new associate justice laid down a marker in one of his very first cases, which involved the First Amendment. “With neither the constraint of text nor the constraint of historical practice,” he wrote, in In re the Reports Committee for Freedom of the Press, “nothing would separate the judicial task of constitutional interpretation from the political task of enacting laws currently deemed essential.”

He issued a blistering dissent in Johnson v. Transportation Agency, a case involving affirmative action in hiring, where he insisted that “a statute designed to establish a color-blind and gender-blind workplace has thus been converted into a powerful engine of racism and sexism, not merely permitting intentional race- and sex-based discrimination, but often making it, through operation of the legal system, practically compelled.”

He would later loudly extol the value of the separation of powers in the Constitution. “The allocation of power among Congress, the president, and the courts in such fashion as to preserve the equilibrium the Constitution sought to establish,” he announced in his dissent in Morrison v. Olson, a high-profile battle over the independent counsel statute, “so that ‘a gradual concentration of the several powers in the same department’ can effectively be resisted.” As Rosen writes, “with Olson, Scalia came of age on the Court: a dazzling demonstration, all at once, of reverence for separation of powers, textualist discipline, literary genius, and institutional courage.”

Scalia also stood unapologetically against social currents, writing in dissent in Romer v. Evans, a historic gay rights case, that “the principle underlying the Court’s opinion is that one who is accorded equal treatment under the laws, but cannot as readily as others obtain preferential treatment under the laws, has been denied equal protection of the laws” — a result that he claimed indicated that “our constitutional jurisprudence has achieved terminal silliness.”

The justice never minced words. “My hope is not to be influential,” he once said. “It is to be right: to be faithful to my oath, which is to apply the Constitution.” That commitment, however, occasionally backfired. He managed to alienate colleagues ranging from Brennan and O’Connor to Justices Harry Blackmun and Anthony Kennedy. Brennan was “disappointed” by Scalia’s criticisms of his many “three-pronged tests” and “balancing acts.” Blackmun’s law clerks engaged in a scurrilous written campaign against their counterparts in Scalia’s chambers, apparently with their boss’s approval. While O’Connor never outwardly showed it, she must have been stung by Scalia’s occasionally personal written rebukes of her “emotional” rulings. Kennedy fell out with Scalia after the former’s defection from the pro-life camp in 1992’s landmark Planned Parenthood v. Casey.

Scalia also refused to court the media, which, unsurprisingly, reported out his interpersonal conflicts with barely disguised glee. A typical Wall Street Journal front-page headline read, “Despite Expectations, Scalia Fails to Unify Conservatives on Court.” At all times, the justice remained faithful to his principles, once telling CBS News in the wake of a controversial 1997 report alleging a lack of racial diversity among court clerks that his selection process was “rigorously fair, that I hire the best and the brightest that I can find.” The reporter asked, “Regardless of race?” Scalia rejoined, “Of course, regardless of race.”

Throughout his career, his wife Maureen remained his north star. “You can’t tell the story of Nino Scalia without Maureen,” said Brian Lamb, an old friend and colleague and the founder and CEO of C-Span. Another colleague recalled the justice saying, “God bless Maureen. She puts up with me and keeps the whole ship moving.” The same colleague also took care to note that Maureen “also had a very clear-eyed view of Nino and would not put up with his bulls***.” This sentiment echoed Meg Scalia Bryce, the youngest child, who noted that “my mom gave Dad a run for his money…put him in his place if he needed to be.” At his swearing-in ceremony, the justice himself credited his wife, “an extraordinary woman,” with his success: “without her, I wouldn’t be here.”

THE BEGINNING OF THE END OF SLAVERY

His personal friendships with Ginsburg, Justice Stephen Breyer, and other liberals like the legendary advocate Nathan Lewin also distinguished and shaped him. Then, too, he exhibited grace and warmth to those who litigated before him. Rosen relates the hilarious story of when, amid a massive 1996 blizzard, Scalia and Justice Kennedy collected legendary Supreme Court advocate Carter Phillips in a Hummer driven by U.S. Marshals and arrived at One First Street in time for oral argument. (No less amusing is the author’s tale of his first encounter with his subject in the late 90s in an Italian restaurant near the Marble Temple.)

Rosen’s second volume ends with a justice in a state of near-permanent dissent (apart from Bush v. Gore, which bore its own hardships), a frustrating position that led him to seriously weigh retirement. Understanding how Scalia turned things around in the 2000s, when his quest for originalist truth finally led to the holy grail, will have to await Rosen’s promised third volume.

Michael M. Rosen is an attorney and writer in Israel, a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, and author of Like Silicon From Clay: What Ancient Jewish Wisdom Can Teach Us About AI