Sing, Muse, of Jeffrey Epstein, the man of many twists and turns who wandered full many ways until his odyssey came to an end in a cell in the Metropolitan Correctional Center in New York, where, despite being the most famous suspect in the land, no one was watching as he did or did not kill himself. Epstein’s life and crimes are an American epic, Homeric in scale, appetite, and immorality. The 3.5 million pages of material in the Justice Department’s information dump of Jan. 30 would, if printed, amount to about 1,000 copies of War and Peace or around 5,000 copies of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey in a single edition.

The release of so much material in a single day was either an act of hope or despair. It trusted that people would exercise their reason and not go off the deep end again into a further fruit-loop of conspiracy theorizing. If they did, then the business was done with either way, whatever it meant, because no one really knows anyway. In a land where everyone is a Jay Gatsby, the author of his, her, or their own lives, everyone has the right to make their own Epstein, just as he made of himself what he could.

In Erwin Schrödinger’s thought experiment, the cat is in a black box with a Geiger counter and a phial of radioactive poison. The cat is both dead and alive because the radioactive matter is both decayed and not decayed, and we don’t know which until we open the box. Epstein is Schroedinger’s crook. Make of him what you will, or what you can, because the files are only half the story, and not just because of the redactions. The first half of Epstein’s variegated career occurred before the internet took off. His correspondence from before the mid-1990s is as lost to us as the records of the petty kingdoms of the late Bronze Age. There are hints of this earlier half-life here and there, but nothing detailed about the sources of the wealth that launched him in New York in the late 1980s after a sojourn in Europe.

Nor do the files contain a big reveal about espionage. Their release occasioned a death rattle of conspiracies about the Mossad and a rash of pieces in the British press in which unnamed “intelligence sources” claimed that Epstein was a Russian spy, albeit the first to write it all down on Microsoft Outlook. The only intelligence source to actually put his name to this nonsense was the ex-MI6 analyst Christopher Steele, he of the discredited “Steele Dossier.” In 2016, Steele purported to prove that Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump was an agent of Russian President Vladimir Putin. The dossier bore the fingerprints of the Democratic National Committee, Hillary Clinton’s campaign, and members of the U.S. intelligence community.

If Epstein was an agent of a foreign power, it would have been most remiss of American intelligence agencies not to have noticed. Epstein had a stellar guest list, extensive offshore travels and foreign banking exploits, and an address book of international connections in key areas of national interest. If American intelligence agencies missed him, it should be a scandal. Almost as much of a scandal, perhaps, as the one that would ensue if our intelligence agencies had tapped into Epstein’s information networks and decided that turning a blind eye to his habitual sex abuse and trafficking was a collateral cost worth paying because it was paid by other people’s daughters.

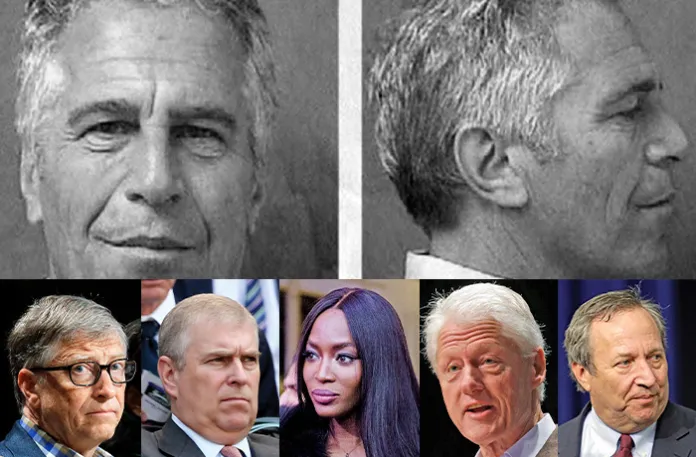

If Epstein was a Russian agent, then a quick search of the files shows that the only American president to slip into his evil net and hot tub was Bill Clinton. Trump figured Epstein for an outer-borough chancer from the start, probably because it takes one to know one. Trump turned down Epstein’s freebies. Clinton took the lot. So did freeloading supermodels (Naomi Campbell), dimwitted second-tier royals (Prince Andrew and sundry Norwegians), and ostentatiously smart Harvard types who weren’t as smart as they thought (Noam Chomsky, Steven Pinker, Lawrence Summers, Alan Dershowitz). This is not the profile of an espionage network. It is the profile of the winners of the 1990s status economy.

A future past

The friends of Epstein orbited around the Clinton-era Democratic Party, the cutting-edge life science labs of the Ivy League, the internet-enhanced networks of global finance, and, of course, image businesses such as Hollywood and modeling. These were the leading edges of American life in those days. They were the kind of businesses in which quick, status-boosting money could be made. Nodal players in the social and professional networks that connected them traded in “access.” At the time, this was celebrated as all-American, new-frontier wealth creation. Take away the ugly scientists and add some surplus royals from Ghislaine Maxwell’s snooty address book, and you have the friends of Harvey Weinstein, the esteemed Hollywood producer and Democratic money bundler who also promised money and influence and also turned out, much to the surprise of all of his friends, to be a serial sex offender.

A fashionable conceit of the age in which the global economy connected everyone was that everything was connected in an invisible network. One of the books of the age was James Gleick’s 1988 book Chaos. In chaos theory, the proverbial twitch of a butterfly’s wing in the Amazon could trigger a ripple of effects that ended in financial panics and the collapse of governments in the kind of small states that now bobbed on the waves of the global economy like drowning rats. The promise of the age was that computer processing would extract patterns from the data. A new mathematics of complexity would emerge from the expanding disorder of entropy.

This kind of thinking runs through Epstein’s emails to scientists and investors. He seems to have carpetbagged himself into a position as a node in the new information networks. He vacuums up gossip and speculation about new products in technology, finance, and politics. All are much the same, because all operate in the singularity of chaos that is the expanding global market, and all roads lead back to Wall Street. Epstein produces coherent sales pitches that suggest imminent opportunities for profit and pleasure, whether political or financial, status-related or sexual, but he also offers a coherent image of the long-term alteration that everyone knows will ensue from the technological-financial shift. The presence of his Harvard chums functions for investors as the public-facing equivalent of the private-facing young girls he procures for his friends: as a bait and an endorsement.

Much of this ’90s fantasy came true. Though the global economy is disaggregating along the fault lines of regional power, it still operates as a single system whose common rules were affirmed in the years of American hegemony (1990-2008). The “singularity” that Ray Kurzweil predicted exists in prosaic form everywhere around us. The world buys and sells in a common digital language, and the commercial application of AI will deepen its presence in our lives. As for the afterlife, ’90s-style transhumanism remains Silicon Valley’s alternative future. The fulfilment of ’90s prophecy is still ongoing: The second Trump administration will be remembered as the moment when the Valley began to merge with the Swamp and Wall Street, with transformative effects on all three.

Though the technological future of the 1990s arrived as predicted, its political future did not. After failing to conquer the globe, liberal democracy has contracted into its Atlantic core, either to recuperate or to expire. The political reality was the crash of 2008, the failures of the War on Terror, the return of near-forgotten class antagonisms, mass immigration, the onrush of globalized Islamist terrorism, and, not surprisingly, middle-class revolts across the Western democracies. The resulting political disillusionment broke both the Republican and Democratic parties.

Historically, this kind of transformation alters the power balance within the ruling class. Usually, one faction rotates into power by mobilizing popular discontent and new ideas, another rotates out by failing to keep up with both, and the ruling class keeps ruling. This rotation has been underway in America since 2016. The MAGA rhetoric of constitutional restoration is a patriotic fig leaf for oligarchic infighting within the ruling class. Red or blue, technocratic or populist, its political leaders remain oriented toward the green fruits of foreign funny money. The Trump family sells bitcoin to the Emiratis as the Biden family consulted for Chinese and Ukrainian energy companies. This exploitation of the nation’s highest office began with the Clintons as an unforeseen effect of globalization. We will know that globalization really is over when America again has a first family that enriches itself solely from domestic sources.

The future that never came to pass is embodied in the Clinton Foundation. A money laundry for the soiled goods and successful strategies of the 1990s, the William J. Clinton Presidential Foundation was set up in 2001 while the Clintonites rotated out of office but not influence. In 2013, as then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton prepared to recover her husband’s old job, the foundation was renamed the Bill, Hillary & Chelsea Clinton Foundation. Donations surged in the run-up to the 2016 elections, with the Foundation netting multimillion-dollar acts of spontaneous generosity from the family-run governments of Qatar, Kuwait, Oman, and Saudi Arabia, and a $2.35 million donation from the family foundation of the chairman of the Russian energy company Uranium One.

Had Hillary Clinton gone over a little better with the public in 2016, her future and ours would be different. Perhaps Epstein’s future would have been different, too. Was his arrest in the summer of 2019, after getting off a private jet from part of the lawfare that dominated the first Trump administration, one move among many in Trump’s long campaign to avenge himself against the Clintonites and the New York power brokers who snubbed him? We may never know. To me, and I imagine to most people, this does not sound as improbable as Epstein’s Zorro Trust winning $29.3 million from the Oklahoma Powerball Lottery in August 2008, when Epstein was just over a month into his sentence for soliciting the prostitution of minors in Florida. That actually happened.

Ehud, Petey, and Jeff

Accidents of democracy forestalled the Democrats’ future in the heart of the American empire, but that future continued to develop in the distant provinces. When the Epstein files came out, the butterfly’s wing operated as Gleick had predicted in the lost age when the internet was a backup communications system in case of nuclear war, Barack Obama was building community in Chicago, and Trump was a casino builder in his first marriage. A tsunami of scandal washed over America’s two closest allies, Israel and Britain.

American allies followed the American path to prosperity in the 1990s just as they had followed American orders in search of security during the Cold War. Sociologists call it “path dependency.” A generation of social democratic politicians rode the promise of Clintonian “third way” economics: Tony Blair in Britain, Ehud Barak in Israel, Gerhard Schroeder in Germany. This new cohort recognized the need to update their countries’ institutions. When they reshaped their governments to run on the new networks of globalization and the internet, they became the unacknowledged spirit guides of the new permanent bureaucracy and the local equivalent of the “permanent Democratic majority.” When their parties lost their majorities, they retained their institutional power and connections, much like the Democrats, only smaller.

Imperial values are always shown in sharpest relief in the colonies. Britain and Israel are American satellites. They are much more intimate with America’s power structures than Puerto Rico or the U.S. Virgin Islands, because they are much more useful. Their economies feed into tech and military research and development and the financial industries. Their military and civilian leadership train in America. Their entrepreneurs, academics, and media aspire to work in America. Their spies work with America. Just as the American markets’ need for information created a demand for an Epstein, so it created suppliers such as Barak and Britain’s Peter Mandelson.

Barak was Israel’s quintessence of ‘90s optimism in its swords-into-ploughshares mode. An ex-special forces leader, Barak rose rapidly to the top of a Labour Party that, though it had lost its default grip on the voters in 1978, still ruled the institutions of the state that it had built. Barak squeaked Israel’s 1999 elections with a nudge from the Clinton administration but crashed out in 2001 after failing to secure a two-state deal with Yasser Arafat. He returned as defense minister from 2007 to 2013 as a junior partner under his Likud rivals, Ehud Olmert and Benjamin Netanyahu. After that, he developed his military and political connections in Israel’s burgeoning tech sector. In the Epstein files, Barak seeks introductions to investors, some American and others Russian, in surveillance tech products. He supplies connections in his Israeli circles but is outside the loop of Israeli politics.

The Israeli Left collapsed in 2001 and has never won an election since. Barak still has useful links to its tech and security sectors, but his erstwhile army colleague and political nemesis, Netanyahu, dominates electoral politics. Netanyahu is not implicated in the Epstein files. He was one of the Jeremiahs who warned in the 1990s that chaos, not order, was coming, and was decried as an enemy of progress for his troubles. Part of his electoral appeal is his promise to root out the Left from Israel’s institutions. While Barak wants to deepen the 1990s’ relationship between Israel and the U.S., Netanyahu wishes to renegotiate it.

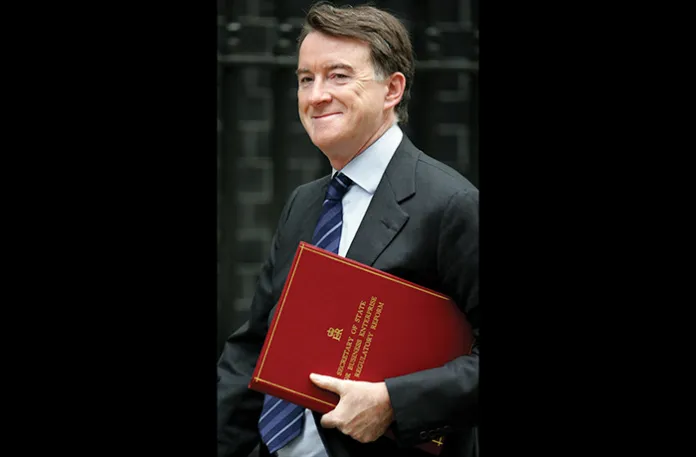

Barak is not in power, but he remains influential because he tells his American patrons what they want to hear. Mandelson, recently removed from power, is influential because he tells everyone what they want to hear. In the ’90s, Mandelson was the brain behind the rise to power of New Labour under the local Clinton impersonator, Blair. Allegations of corruption twice forced him from office in the early 2000s, once under Blair and again under Blair’s successor, Gordon Brown. This did not stop Brown from promoting Mandelson to the House of Lords in 2008. Nothing, it seems, could stop Mandelson. He was one of the string-pullers who masterminded New Labour’s recovery of control over the party in 2019 and backed Keir Starmer as its leader.

When Starmer won the 2024 elections, he made Mandelson the ambassador to Washington. Mandelson’s intimacy with Epstein was public knowledge: Emails had already come out showing that “Petey” and “Jeff” were good friends long after Jeff’s conviction as a pederast and pimp. Starmer’s team, and most of the British media, argued that the best way to influence a venal crook such as Trump was to send someone who spoke his language. The Epstein files show that when Mandelson was in office, he leaked confidential government information to Epstein, including tip-offs that gave Epstein prior knowledge of market-shifting news, and sought to pressure the British government on behalf of Epstein’s friends at J.P. Morgan. Starmer’s government was already tottering before this scandal broke. It is now in full catatonic zombie mode.

The path has not yet run out for American allies. But the way forward is no longer as clear or straight as it once was. Chaos, the fructifying virtue of the American-run system of the 1990s, has spread through both the global system and America’s domestic polity. At home and abroad, institutional dependencies linger on and paralyze the chances of political revival. The reputations of Barak and Mandelson were already rotten before we discovered what they were up to. We will know that the 1990s are really over when we are allowed to know the full story of Epstein.

Dominic Green is a Washington Examiner columnist and a fellow of the Royal Historical Society. Find him on X @drdominicgreen.