The Chicago Cubs, improbably, were riding a nine-game winning streak on Sept. 14, 1953, facing the first-place Brooklyn Dodgers for the second game of a two-game set. The home-field Cubs would beat the Dodgers again that day to make it 10.

Overall, though, it was a miserable season for the Cubs, and the game wasn’t memorable for anyone, specifically, on the field that day. Instead, it was notable, seven decades later, for the middle infielders watching from the bench — men who played key roles, some of them long forgotten, in the history of baseball’s integration, and thus in the history of the United States.

Jackie Robinson, Brooklyn’s second baseman, was one of them. An elbow injury kept him out of the lineup that day. Shortstop Pee Wee Reese, Jackie’s longtime double-play partner, and a white Southerner who stuck his neck out for Jackie in his first year, was also sitting out the game.

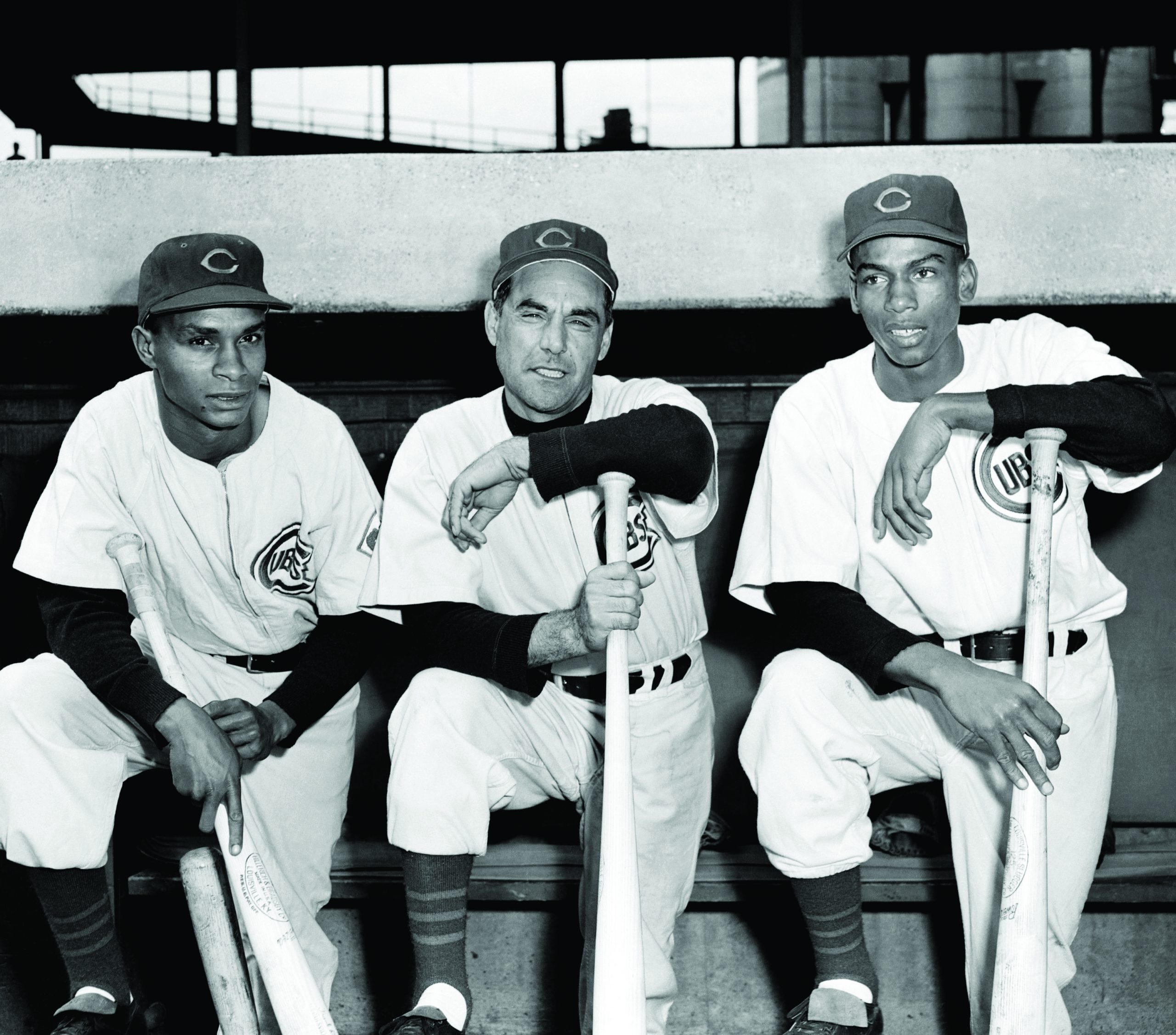

A trio less famous, but deserving of more credit than history has given them for their role in desegregating baseball, were riding the pine in the home dugout. As the Chicago Tribune reported the night before: “Gene Baker, Negro shortstop … will arrive by plane tomorrow morning. Shortstop Ernie Banks, purchased from the Kansas City Monarchs, also is due tomorrow.”

There was a third shortstop on the Cubs’ bench that day, who was not nearly as young as Banks or Baker: the 36-year-old son of an Italian immigrant, Bob Ramazzotti.

Gene Baker had spent years in the Cubs’ minor league system, designated long ago as the shortstop of the future and the man who would finally break Chicago baseball’s color barrier. Due to a minor back injury he had suffered during one of his final minor league games, he was on the disabled list until Sept. 20.

Banks wouldn’t get into the starting lineup until a few days later, but before that game against the Dodgers, he was, unlike Baker, able to take part in batting practice. On his very first swing, he parked the baseball in Wrigley’s bleachers.

Banks, not Baker, at that moment became the shortstop of the future. Banks, who shared a birthday with Robinson, would also become the next crucial chapter in baseball’s integration. Banks was naturally more gregarious and easy-going than Robinson. Whereas Jackie became widely admired, Banks became universally loved. Whereas Jackie meant something to all of baseball, Ernie meant everything to the Cubs.

That wasn’t great news for Baker, who had to shift to second base to be Banks’s supporting player. And Ramazzotti? He spent the second half of September 1953 teaching Baker how to play second.

It was a fitting coda to the career of the man who in 1947 had lost his job to Jackie Robinson.

Altoona’s finest

Bob Ramazzotti was a true ballplayer. “Courage and grit” is how one biographer described him. Bob’s father Paolo Ramazzotti was, like most men in Altoona, a railroad worker.

Bob was a ballplayer in central and western Pennsylvania, competing in the minor league towns along the rail lines and on the banks of the Monongahela and Allegheny rivers. His gritty play caught the eye of scouts for the Brooklyn Dodgers’ organization. One Dodgers coach compared Ramazzotti to Honus Wagner, a Hall of Fame infielder.

“RAMY STILL HUSTLING,” blared the Altoona Daily Herald’s headline on June 11, 1940. The 23-year-old infielder had smashed two home runs that day in a minor league game. “Afield he handed six chances without a boot,” the paper noted proudly of its hometown boy.

“Ramy’s work to date can hardly fail to impress Brooklyn Dodger scouts and it would not be surprising if the former Millville and Columbia Park shortstop winds up the season in a league of a higher class.” He made the Penn State Association’s all-star team as the shortstop in 1940, and that September, the Dodgers summoned him to Brooklyn — to the big leagues.

“The recall of Ramazzotti to Brooklyn is considered unusual inasmuch as major league clubs seldom pluck boys out of Class D ball,” his local paper, the Altoona Tribune, reported. “However, Dodger officials have heard so many glowing reports of the great young shortstop that they are anxious to see him perform in Ebbetts field.”

Ramazzotti got the tryout that fall, but he didn’t make the roster. Still, he was on the brink. Rabbit Maranville, a major league infielder-turned-minor league manager, said, “Ramy is no more than three years out of the majors,” as the Altoona Tribune paraphrased it.

Ramy continued that trajectory, but luck wasn’t on his side. Instead of sucking up grounders in Ontario in 1942, Ramazzotti was fighting in the Rhineland. The rising star spent his prime years, 1942-1945, as a soldier on the Western Front.

When peace came, Ramy finally got his crack at the bigs. With third baseman Cookie Lavagetto injured, and creaky shortstop Eddie Stanky showing his age, “Dodgers president Branch Rickey announced that the team, needing infield insurance, had purchased Ramazzotti from Montreal,” biographer James Forr wrote.

Ramazzotti was, in 1946, officially Stanky’s backup. Things looked bright going into 1947.

But there was another infielder climbing up through the ranks with a chance to land on the big league club that year: a fellow by the name Jackie Robinson.

On April 3, 1947, the Dodgers played a preseason game against the Montreal Royals, their own AAA club. Branch Rickey, the owner, had taken the extraordinary step of ordering Montreal’s manager to start Robinson at first base.

The sports writers all knew the significance: The Dodgers were planning on calling Robinson up to the big leagues. Because Stanky was still all-star caliber, Robinson would play first base for a year, but they were eyeing him as Stanky’s eventual replacement at second.

Down near the bottom of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle article reporting the Robinson news, almost as a footnote, the reporter mentioned, “Bob Ramazzotti has been dispatched to St. Paul on option.” Ramy had been sent back down to the bush leagues.

Sure enough, Jackie Robinson spent the historic 1947 season in the Dodgers infield, winning Rookie of the Year. Bob Ramazzotti spent the entire season back down at St. Paul, where a minor league pitcher plunked him in the temple with a fastball, putting Ramy on death’s door.

The Dodgers traded away Stanky before the 1948 season. The slot Ramazzotti had been eyed for was open, but not for Ramazzotti. Jackie Robinson would play most of the season at second for the Dodgers in 1948 and hold down a starting role in Brooklyn for a decade. Ramazzotti, on the other hand, spent 1948 juggling injuries and bouncing around the Dodgers’ minor league clubs, before the team let him go.

For a few more years, Ramazzotti popped around the minors and majors, landing on the sad-sack Chicago Cubs while Robinson, Rickey, Reese, and Duke Snider were building a dynasty in Brooklyn.

Mr. Cub’s sidekick

Six and a half years after Jackie Robinson Day, shortstop Ernie Banks took the field as the first black man ever to play in a Chicago Cubs uniform. Two-thousand five-hundred and twenty-eight games later, Banks retired in those same pinstripes with the nickname “Mr. Cub,” and a ticket punched for the Hall of Fame. His role breaking the Cubs’ color barrier was part of his fame, but so were his 511 home runs, his 13 All-Star appearances, his two MVPs, and the first-ever Gold Glove for a Cubs player — at shortstop in 1960.

But Banks wasn’t the first black man on a Cubs roster. That was Gene Baker. Baker, though, didn’t actually get put into a game until three days after Banks did.

Baker was supposed to be first. At one point, he was supposed to be the Cubs’ starting shortstop. But both of those honors went to Banks, and Baker had to cede shortstop to Banks and learn second base. If “Mr. Cub” sounds like a comic strip hero name, old Gene Baker was the trusty sidekick.

Baker had some valid complaints, but they weren’t about Banks playing shortstop over him in 1953 and beyond. The wrongs done to Baker were done earlier, when a mix of cowardice and racism kept him in the minors for four seasons, well after Robinson had broken the color barrier.

“The Cubs were guilty of what is, arguably, the single most conspicuously prejudicial treatment of a black player since the color line was crossed,” writes baseball historian Rick Swaine. “To the detriment of the team, Cubs’ management refused to promote infielder Gene Baker who was clearly one of the top players in their organization. Baker would spend four seasons — the prime years of his career — starring in the Cubs’ farm system rather than Wrigley Field.”

In 1950, Baker was 25 years old, and he quickly emerged as the best infielder in the Cubs’ minor league system. He was promoted to the Cubs’ Triple-A team in Los Angeles, the highest of the minor leagues, and he made the all-star team. Then, in 1951, he was again an all-star shortstop at Triple-A — a feat he repeated in 1952 and 1953.

Being the best shortstop in the Pacific Coast League is quite a thrill. But being the best shortstop in the Pacific Coast League for four straight years has a different salience. It was an indignity. It was obvious that Cubs owner P.K. Wrigley was dragging his feet on integration.

Baker’s fielding at short was unmatched. His hitting was solid. And he was an extraordinary student of the game. “He knows more baseball than fellows twice his age,” one of his managers would say. “He’s one of the smartest I’ve ever met.”

Yet the Cubs kept Roy Smalley at shortstop, where he led the league in errors three years in a row. (His 1950 mark of 51 boots has not been topped since.)

His partner in the middle infield, second baseman Eddie Miksis, wasn’t much better. Commentators described the Cubs’ double-play combination as “Miksis-to-Smalley-to-Addison.” Addison Street was the road that ran behind first base at Wrigley.

The disparity between the sad play of the white ballpayers in Chicago and Baker’s stellar play in the minors became too gaping for any honest observer to ignore. Cubs management reassured the media in 1952 that Baker was coming up: “We’re bringing him up in 1953 as the first Negro to wear a Cub uniform.”

Yet come Opening Day, management announced Baker would once again be in the minors “for further seasoning.” Baker had seasoned plenty. He was arguably peaking — turning 28 in the minors in the summer of 1953. Chicago moved their shaky second baseman Eddie Miksis to shortstop to replace Smalley. Miksis quickly became a shaky shortstop.

Finally, come fall, the Cubs announced Baker would join the major league roster after the minor league season ended. In one of his last at-bats in the minors, Baker tweaked his back on a swing-and-miss. The Tribune reported on Sept. 1, “The Cubs yesterday announced the purchase for an undisclosed sum of Shortstop Ernest Banks from the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League.”

“Two Negro youngsters,” reported the Tribune on the morning of Sept. 14, “who will challenge Roy Smalley for his shortstop job next season, arrived in Chicago yesterday from opposite ends of the country.”

“Ernie Banks flew in from Pittsburgh, where he had said farewell to the Kansas City Monarchs after Sunday’s game. Gene Baker arrived by plane by San Francisco.”

That day was the day Baker was limited to a light workout and Banks connected for a homer on his first batting practice pitch. When Gene Baker finally took the field at Wrigley, on Sept. 20, 1952, at age 28, it was at second base — a new position for him. The Cubs’ less-than-courageous management had held off on bringing up Baker until they could find a second black player — this would provide Baker some companionship and ensure no white player had to room with Baker.

Baker was an all-star in 1955, but he was never the star of the Cubs infield. He was, instead, a supporting player in Banks’s story, which was one of many sequels to Jackie Robinson’s story. Banks would call Baker “one of the greatest people I’ve ever known. I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for him.”

In the story of integration, Baker has a solid claim to being a more important character than Banks. Banks kept quiet in those early days, following the advice Jackie Robinson had given him. “Gene Baker, he was different,” Banks would say later. “He was from Iowa, and he had played in Los Angeles against white players and had more experience.”

Baker wasn’t going to let white players treat black players as if they didn’t belong there. Once, their rookie year, Baker informed Banks, “All these guys are angry with you.”

“For what?”

“You’re hustling too much. You’re showing everybody up.”

“I thought you’re supposed to play hard. What should I do?” Banks asked.

“Keep on doing it.”

The pair would turn hundreds of double plays together in Chicago, and in 1955, they were the only two Cubs to play every single game.

Banks would say of Baker, “He was the brightest guy I’ve ever been around. He allowed me to learn from my own experiences.” Baker would, in 1961, become the first black manager in organized baseball.

But even as a supporting character, the wind beneath Ernie Banks’s wings, Baker had his own supporting character. He had never played second base before September 1953, and he needed someone to train him on that position. Luckily, the Cubs had on their roster a veteran infielder up to the task — a ballplayer who had started as a shortstop and made the transition to second base: a 36-year-old in his final season by the name of Bob Ramazzotti.

Timothy P. Carney is the senior political columnist at the Washington Examiner and a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He is the author of Alienated America: Why Some Places Thrive While Others Collapse, The Big Ripoff, and Obamanomics.