Serena Williams is unquestionably one of the greatest athletes in history. She has won 23 Grand Slam singles championships (one short of Margaret Court’s record), 73 WTA titles, four Olympic gold medals, was the No. 1 women’s player in the world for 319 weeks (trailing only Martina Navratilova and Steffi Graf), and is the highest-earning female athlete of all time in career prize money. Unlike her male contemporaries Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal, and Novak Djokovic, Williams has had an exceptional career as a doubles player as well, winning 14 Grand Slam doubles championships with her sister Venus without ever losing a single final. She has even won two Grand Slam mixed doubles championships. Williams also differs from Federer, Nadal, and Djokovic in that she is arguably the only tennis player of this generation to have transcended her sport, becoming not only “Serena Williams” but “Serena” — a one-name cultural icon on par with Madonna, Beyonce, and Oprah.

Serena’s backstory is almost as well known as her accomplishments. Raised in Compton, California, Serena and Venus were trained by their parents, Richard and Oracene, to become tennis players from the time they could walk. All this and more has been exceedingly well documented in the plethora of stories that have appeared about the sisters since their early teenage years and has been further elaborated upon in the nearly dozen books by and about them, including Serena’s 2009 autobiography, On the Line, and Richard’s 2014 autobiography, Black and White: The Way I See It.

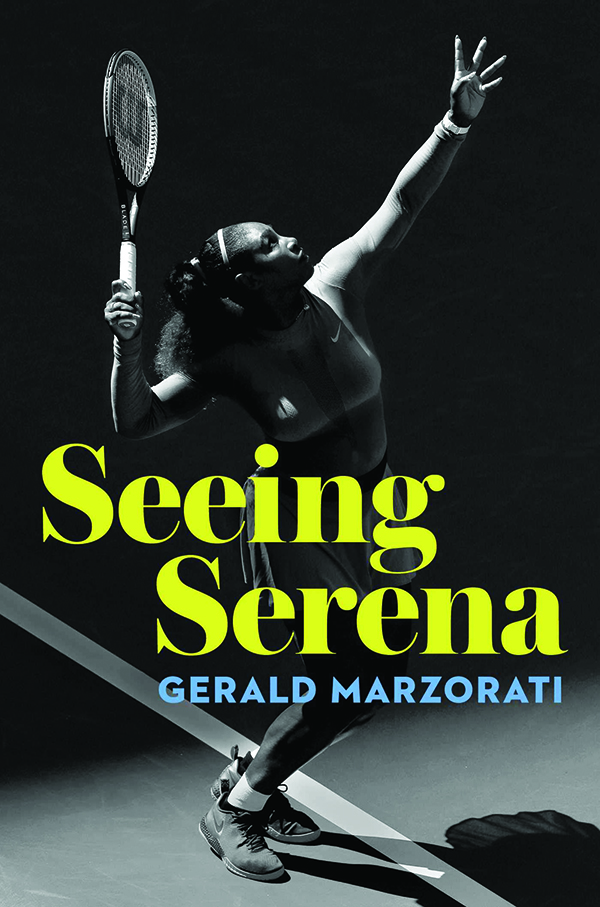

To this teeming multitude of books and stories, Gerald Marzorati, a tennis writer for the New Yorker and author of the memoir Late to the Ball, adds Seeing Serena, a brisk stroll through her 2019 season. Seeing Serena sets out to follow Williams through one year on her quest, at the age of 37, to win her record-tying 24th Grand Slam and her concomitant attempt to win her first major as a mother, something only three other players, one of them being Court, have accomplished. It quickly becomes apparent, however, that Seeing Serena is about much more than Serena and her 2019 season.

Though Marzorati recapitulates much of what is already known about Williams and her family, he provides useful, fluidly written summaries of other players, coaches, and institutions in the tennis world. We learn about Williams’s coach Patrick Mouratoglou, a Frenchman with a Greek father and French mother whom Marzorati describes as “tennis’s answer to Bernard-Henri Levy,” and about the “Moneyball guy” of tennis, Craig O’Shannessy, an analytics specialist who’s been employed by Djokovic, Sloane Stephens, and Maria Sharapova. We learn about the burdens and responsibilities of being a professional tennis tournament director and about Qai Qai, Serena’s daughter’s doll, which “uses” Twitter and has its own Instagram account with over 100,000 followers. And for readers unfamiliar with Williams, there’s information on her biggest rivals, including Justine Henin (one of the few players with a winning record against Williams) and Naomi Osaka, and charming anecdotes, including the one about how she met her husband, Reddit co-founder and tech entrepreneur Alexis Ohanian, by chance at a hotel in Rome, where she was staying for the 2015 Italian Open.

Much of this will be quite appealing to tennis fans seeking to deepen their knowledge about this era of women’s tennis, but for some reason, Marzorati feels compelled to explain just about every aspect of the game to readers: not only arguably lesser-known aspects of tennis such as foot faults but also more elementary aspects of the sport, such as the fact that “the T” is the area on the court “formed by the intersection of the center and service lines,” that a “first serve coming at the returner is the hardest-hit ball she’ll face in a match,” and that the quarterfinal is the round of a tournament in which a player can advance “on to the semis and, just maybe, the final.” And then — let me guess — the final is where a player can win the tournament? Readers with even the most rudimentary understanding of the sport will at times feel like they’re reading Tennis for Dummies. The book gets better when Marzorati starts talking about things such as the dynamics of topspin, the particular demands of clay court tennis, and the finer points of Williams’s game.

The excellent tennis talk is enlarged (or subsumed) by recurrent conversations about Williams’s identity. Nearly every episode of the book is filtered through the prisms of race and gender, so much so that it often feels like Marzorati regards Williams less as a transcendent tennis player who happens to be black than as a transcendent black woman who happens to play tennis. Marzorati appears to admit as much, stating in the book’s epilogue that Williams and her remarkable career “remind us that sports cannot and should not simply be an escape, that struggle is everywhere and ongoing.” Seeing Serena is a fascinating glimpse into the life of one of the greatest tennis stars of all time, but if you’re looking for a respite from the most contentious social and cultural issues of the present, you won’t find one here.

Daniel Ross Goodman is a postdoctoral fellow and research scholar at the University of Salzburg and the author of Somewhere Over the Rainbow: Wonder and Religion in American Cinema and the novel A Single Life.