The New York Times’s recent decision to strip bylines from the stories linked on its home page prompted outcries from journalists outside the paper. They follow certain reporters from the Times, not necessarily the Times itself, went the argument; removing the reporters’ names from the front page made it more difficult to notice their work. The implication is that such readers are readers of Reporter X before they are readers of the paper itself.

Twitter users have no such benefit. The platform is wholly egalitarian: Eminent journalists share publishing space with politicians and political operatives, celebrities, anonymous trolls and bots, childish provocateurs, and the most typical group of them all, normal people. Almost any author on Twitter has the potential to be the day’s most-read user—a quirk of the system that extends to individual users who follow someone like Chris Hayes (1.7 million followers) but not the anonymous tweeter of a viral hoax.

The reportorial consequences of this flat playing field have been evident from the platform’s launch. Twitter cofounder Biz Stone provided an innocuous scenario in 2009: “The first Twitter report of the ground shaking during recent tremors in California, for example, came nine minutes before the first Associated Press alert. So, we knew early on that a shared event such as an earthquake would lead people to look at Twitter for news almost without thinking.”

There are many “shared events” other than geological ones, of course. Say, a Supreme Court confirmation hearing, when hordes of rumormongers and incendiaries declare Press badges? We don’t need no stinking press badges. Given that the event is widely broadcast, followed, and galvanizes plentiful participation on social media, there are no limits to who can manufacture “news” about it.

Take the case of a former law clerk to Judge Brett Kavanaugh. Several Twitter users claimed Zina Bash, seated behind her old boss, appeared to be making an “OK” sign with her right hand as it rested on her forearm during Tuesday’s hearing. The Anti-Defamation League explained last year that trolls on the Internet forum 4chan organized to convince the public that the otherwise normal gesture—with the bottom three fingers straight and the thumb and index finger connected to make an ‘O’—stood for “white power.” The ADL does not consider it a hate symbol. But a committed segment of the Trump “resistance” says the sign’s intent as a prank was lost in translation, and therefore this woman must have been signaling her white-power allies—a claim reinforced when it was discovered that she previously was a lawyer in the Trump administration.

A credible reporter would never make such a leap. But editorial discretion was not of concern to a guy named Keith, whose tweet asking “what’s up with the white power sign?” received 18,000 retweets before it disappeared on Thursday. It inspired a similar tweet that’s been retweeted 4,200 times. Which led to another tweet that commented on what constitutes a hand’s natural resting position—that one’s been retweeted 2,400 times. Then came one that showed video of the lawyer checking her phone and then allegedly making the gesture, implying she may have received a reminder or an instruction: 5,700 retweets. After that, someone tweeted a similar clip that checks in at 3,100 retweets. And so on …

If you’ve never seen Twitter spiral out of control, this is how it happens: A critical mass of highly retweeted tweets flies beyond the cuckoo’s nest and gets noticed by the mainstream press. Journalists, in turn, become birdwatchers and comment. As the Times’s Nicholas Confessore quipped, “Zina Bash Truther Twitter is in full effect.” It could appear, at this point, that there is a “story.” Not one that was assembled with careful analysis and vetting of subject material and sources, but one of a genre unique to Twitter: “People on the Internet Are Claiming That Something Is Happening (and Man, Is It Nuts).”

And then there was Fred Guttenberg, the father of a slain teen from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. During a break in the Kavanaugh hearings on Tuesday, Guttenberg approached the judge from out of the blue and extended his arm; Kavanaugh turned and took note of him, stone-faced; a person who White House spokesman Raj Shah identified as security stepped in front of the man almost immediately and nudged Kavanaugh along. Guttenberg wrote on Twitter that he’d been rejected by the judge. His brief interaction with Kavanaugh was more a brush than an encounter—but long enough to be captured by professional photographers and turned into a Claim of Something Happening on Twitter.

Vox provided the most insightful takeaway. “It’s not clear if Kavanaugh heard Guttenberg or if the rebuff was intentional. But amid hearings that have already gotten contentious as Democrats and activists attempt to stop Kavanaugh’s nomination, the moment has quickly gone viral.” Guttenberg’s tweet about the incident was retweeted 71,000 times. A black-and-white photo of Guttenberg extending his hand toward Kavanaugh was retweeted 48,000 times from the account of AP photographer Andrew Harnik.

In other Twitter news: After Nike unveiled its new ad campaign featuring Colin Kaepernick, internet users shared photos and videos of themselves destroying Nike gear. A kid burned some Nikes in a fire—the Twitter video of it has been viewed more than 4 million times. A member of the country band Big & Rich tweeted that his soundman cut the swoosh from his socks: 13,000 retweets. One wonders how many protesters went to such goofy lengths. One also wonders how much it matters, since the number of social shares surely matters more than the number of humans.

These flashpoints trigger news cycles on Twitter: No small deal, since 11 percent of American adults get news from the platform, per data from the Pew Research Center. But does this information migrate off the platform and become news in the mainstream—a journey that subjects it to editorial review? Here, there manifests a disconnect between Twitter and the industry of newspapers, magazines, and television programs, all of which are chronicling the same news developments in real time.

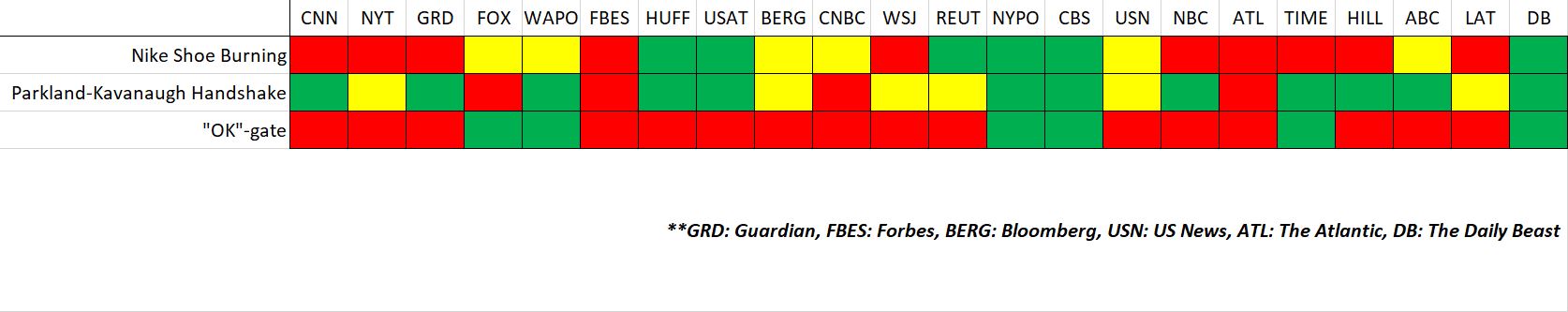

A review of 22 highly trafficked news sites as ranked by Alexa shows that coverage of the two Kavanaugh-related events and the Nike outrage was mixed. A red box indicates that the outlet did not produce a standalone story about the topic the day of the event in question or the one after, and a green box indicates that it did; a yellow box indicates that the topic was mentioned as part of a broader account (during a running blog of the Kavanaugh hearing, for instance).

For the most part, the “OK” nonsense was ignored. Most of the coverage focused on the lawyer’s husband, a United States attorney, issuing a statement condemning the Twitter coverage of his wife. The situation between Kavanaugh and Guttenberg, by contrast, was covered widely, making it one of the top stories from day one of the hearings. The attention paid to the Nike-burning protests was mixed, though several outlets placed it in the context of President Trump condemning the Kaepernick campaign and Nike’s stock taking a tumble.

That the mainstream media paid little attention to a baseless claim about the way an audience member was holding her hand during a televised hearing is reassuring. Nine of ten adults don’t get news from Twitter, meaning that most of the country is unaware of the manufactured controversy. But the week’s events have still demonstrated how Twitter is one of the nation’s most influential “publications.” It is not always a case of spreading “fake news,” as in presenting a provably false claim as fact. Contextual evidence and common sense indicate that Kavanaugh’s former clerk was not reaching out to white supremacists—but there’s not a way to disprove it definitively, for it stems from a loaded question fallacy. A few seconds of Kavanaugh standing face-to-face with a stranger inside a noisy room with no reporters near to document any verbal exchange is a shaky foundation for a story. But images of the scene and claims by the principals involved can feed confirmation biases and produce a top headline seemingly from whole cloth. Such scale could not be achieved without an amplification tool like Twitter.

These moments come and go: On Wednesday afternoon, they were usurped by an historic op-ed in the New York Times and further news from the Kavanaugh hearings. The issue is not necessarily that there is more news to cover than ever. The issue is that more people are attempting to create it—and on a platform with no barriers to entry like Twitter, self-restraint is the only way to stop the flood.