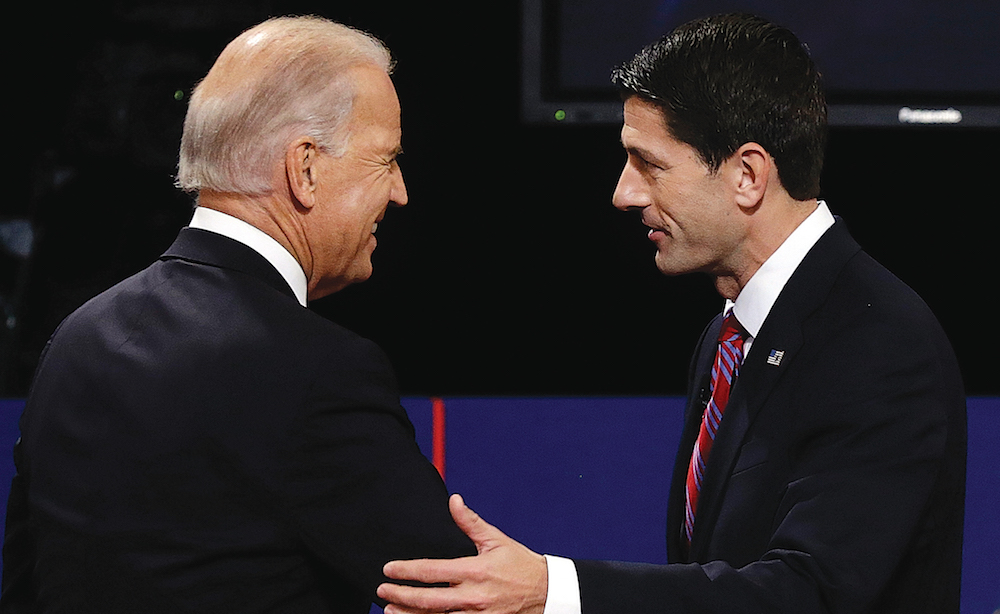

Less than one month before the 2012 presidential election, Rep. Paul Ryan received the toughest criticism Joe Biden had to offer for his proposed reforms to Social Security and Medicare in a debate in Danville, Ky.

“You are jeopardizing this program,” the vice president said, accusing Ryan, who was running to take his job.

“Whatever you call it, the bottom line is people are going to have to pay more money out of their pocket,” Biden said in front of 51 million TV viewers. “And the families I know and the families I come from, they don’t have the money to pay more out.”

Biden won the debate, polls later suggested, largely by putting Ryan on the defensive regarding the budget plans that he authored as chairman of the House Budget Committee, much of which Mitt Romney’s campaign adopted.

Ryan and Romney were willing to risk the election to run on reforms to Medicare and Social Security. They would lose, but Ryan’s vision for reforming government spending and reducing the debt became the de facto Republican platform, later validated by his colleagues choosing him as House speaker.

One Republican who wasn’t impressed, however, was Donald Trump.

When Ryan was drafted to take over the speaker’s office in the fall, Trump warned during a Sunday talk show interview that he disagreed with Ryan’s plans for Medicare and Social Security. The Wisconsin conservative, he said, had hurt Romney’s chances at the presidency because he was “so anti-Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security, in a sense.”

Throughout the primary campaign, Trump has repeatedly pledged to oppose plans to reduce spending on entitlement programs such as Medicare and Social Security, the very programs set to eclipse half of federal spending in the coming years and drive future deficits.

“I’m the only one that wants to do this. And some people will say that is not very Republican of you or conservative of you,” Trump said in an April interview with Fox’s Sean Hannity in which he most clearly laid out his views. “We’re going to save it. People have been paying into their security for years and years. We’re going to save Social Security … We’re going to save it and Medicare.”

As Republicans prepare for the 2016 election, they have a leader in Ryan who spent years building the case for entitlement reform and a presidential nominee who wants to run against that legacy.

Trump has gestured at spending reform, but the cuts he has proposed are worthless in the eyes of the fiscal conservatives who advocated and helped build support for Ryan’s budgets.

Conservatives, and others worried about the rising federal debt, believe that there is no way around it: To prevent a fiscal crisis, Congress must make changes to old-age retirement and healthcare programs to address the reality that 80 million baby boomers have just begun reaching retirement.

Donald Trump has gestured at spending reform, but the cuts he has proposed instead are worthless in the eyes of the fiscal conservatives who advocated and helped build support for House Speaker Paul Ryan’s budgets. (AP Photo)

“There is a moral obligation we have to those we represent to make sure we are addressing the fiscal challenges inherent in a number of automatic spending programs,” Rep. Todd Rokita, the Republican vice chairman of the House Budget Committee, said in a June hearing on spending reform.

Trump’s opposition to such reforms threatens to undo years of intellectual groundwork and coalition-building undertaken by conservative lawmakers and scholars.

Yet that doesn’t mean that the next four or eight years with Trump — or Hillary Clinton — in the White House are hopeless, in the view of fiscal conservatives.

Many say that the debt problem will become so urgent that the next president will have no choice but to pursue serious entitlement reform. And he, or she, will be working with a congressional Republican caucus led by Ryan, whether or not it remains in the majority.

The problem with Trump

A major problem for fiscal conservatives is that Trump’s statements on the debt have been vague and conflicting.

At times, he has sounded like the most aggressive of fiscal hawks, pledging not just to stave off a debt crisis, but to actually pay off the $19 trillion national debt within eight years, a fantastical goal dismissed by budget experts as unthinkable.

A Trump aide went so far as to suggest, at a May event in Washington, that Trump’s policies would yield a $4.5 trillion-$7 trillion surplus within 10 years. Such a result would not even necessarily be desirable. Republicans, in particular, would chafe to see the government collecting income taxes while having trillions in the bank.

Yet Trump has promised to cut taxes more than any other Republican, which makes his promises to reduce the debt even harder to believe. Of the few specifics he has offered on the campaign trail, the most detailed is his promise to cut taxes by nearly $10 trillion over the next decade, or a quarter of total government revenue.

Those tax cuts could not pay for themselves by spurring faster economic growth, as Trump and his aides have suggested. The Tax Foundation, a nonprofit think tank friendly to business, analyzed Trump’s plan while accounting for the possibility that tax cuts would boost growth, and found that it would cost the Treasury more than $10 trillion, down from $12 trillion in a simulation that didn’t include faster growth.

Trump has promised to cut taxes more than any other Republican, which makes his promises to reduce the debt even harder to believe. (iStock)

While his plans for tax cuts are clear, Trump’s accompanying spending cuts are vague.

Analysts at the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget went through all of Trump’s specific campaign promises and tallied them up for a bottom-line number. The group, a nonprofit that pushes for debt reduction, found that they would add $12.6 trillion to the federal debt by 2026.

As a share of the economy, the debt would rise from 74 percent now to nearly 130 percent, rather than the 86 percent that would be projected if Trump didn’t change any laws.

What is worrying, said Maya MacGuineas, the group’s president, is that Trump is giving voters the false impression that reducing the debt is “really easy to do.” He cannot promise voters that they’ll be taxed much less, that Obamacare will be repealed and replaced with a better program and that the problems at the Department of Veterans Affairs will be resolved while, at the same time, the federal debt is extinguished.

“You have to be willing to level with voters during the campaign,” MacGuineas said, warning that Trump would risk a backlash if he became serious about reducing the debt in office and tried to impose tax increases or spending cuts on an unprepared electorate.

The spending cuts that Trump has outlined cannot stabilize the debt. They are much better suited for pleasing voters, especially considering that he has proposed increasing some forms of spending, such as funding for the Pentagon.

For example, during a Fox News GOP presidential debate in March, moderator Chris Wallace asked what spending cuts Trump would seek to balance out his tax cuts. “Please be specific,” Wallace said.

“Department of Education. We’re cutting Common Core. We’re getting rid of Common Core. We’re bringing education locally. Department of Environmental Protection,” Trump said, misnaming the Environmental Protection Agency.

This year, the Department of Education is expected to spend $79 billion and the EPA $8 billion. Common Core, meanwhile, is a set of education standards implemented at the state level. Assuming that all the spending done by the two agencies would be zeroed out — which is far from clear, given Trump’s other statements — the savings would be swamped by the added spending and tax cuts Trump has proposed.

Trump has identified one other source of spending cuts: waste, fraud and abuse, which he called “massive.”

While much government spending is inefficient or mismanaged, budget experts do not believe that cutting waste, fraud and abuse is a realistic approach to stabilizing the debt.

“That’s a complete sham,” said James Capretta, a healthcare and budget expert with the Ethics and Public Policy Center, a conservative Washington think tank.

Sen. Jeff Flake, the fiscally conservative Arizona Republican, published a version of a “wastebook” in December detailing more than $100 billion worth of wasteful spending through 100 programs in 2015. (AP Photo)

It’s difficult to say just how much waste, fraud and abuse occurs in federal spending. Sen. Jeff Flake, the fiscally conservative Arizona Republican, published a version of a “wastebook” in December detailing more than $100 billion worth of wasteful spending through 100 programs in 2015.

One sample expenditure: The Department of Agriculture gave New Mexico State University $17,500 to fund a weight sensitivity training program in which participants would wear a 20-pound fat suit to experience the social and psychological effects of obesity.

Yet what is a flagrant waste of money to one senator might represent a valuable study to a university, and the budget can’t be fixed one $17,500 grant at a time.

A broader accounting of waste, reported by the Government Accountability Office, Congress’ investigative arm, found $124.7 billion in improper payments across the federal government in fiscal 2014.

Much of that waste, however, is spent through large programs such as Medicare and Medicaid, where it is difficult to root out, and through low-income tax credits that many lawmakers think should be disbursed even if technically they are wasteful under the current rules.

While the federal government wastes a lot of money, the idea that Trump could come in, snap his fingers and end wasteful spending is “plainly not true,” Capretta said.

When the numbers don’t add up

Fiscal conservatives don’t believe Trump’s debt reduction math adds up, and so they are left with two options in a potential Trump presidency.

One is to try to pressure Trump to embrace the congressional GOP agenda and the entitlement reforms backed by Ryan, hoping that the urgency of the rising debt will sway him.

The other is to let Trump be Trump and gamble that the country could survive another four or eight years of rising debt without encountering a crisis, a prospect made more attractive given that the alternative is Clinton.

Some of the same budgeteers who have pushed for years for Congress to embrace the Ryan agenda believe that the fiscal math is such that the next president will have no choice but to attempt to reform the retirement and healthcare entitlement programs that account for so much of the federal budget, whether that president is Trump or Clinton, who has suggested expanding Social Security benefits.

The ultimate problem is demographic, with the number of retirees set to soar.

Eighty million baby boomers, including immigrants, are set to reach retirement age before 2029, a demographic wave that will push the total number of Social Security beneficiaries from about 50 million today, according to the program’s trustees, to 73 million.

As the boomers retire, fewer workers will be available to pay into retirement and healthcare programs. For more than three decades, there have been about 3.3 workers for each Social Security retirement beneficiary. As the boomers have begun retiring, that number has declined rapidly to 2.8 and is set to fall to 2.1 by 2035 when the boomers are mostly finished retiring.

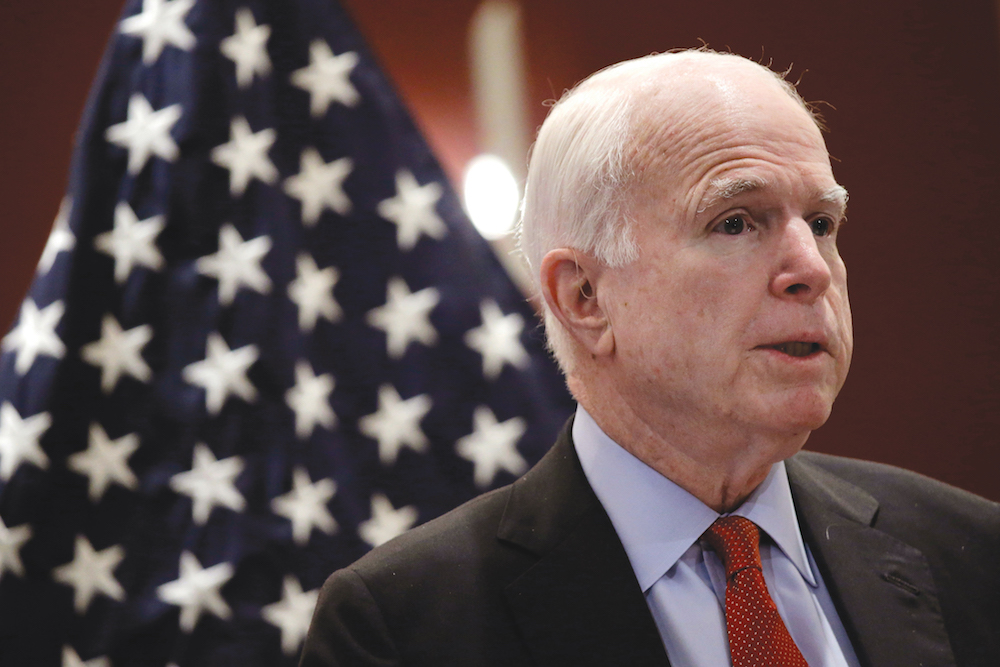

While defense hawks such as Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., have issued dire warnings about the security implications of the spending caps, appropriators and others have said that the caps on agency spending are unrealistic. (AP Photo)

The upshot: Spending on retirement and healthcare programs is rising and revenue will not rise as fast. Combined spending on Social Security, the major government healthcare programs and interest on the debt rose from an average of 43 percent of total federal spending over the past four decades to more than half in recent years.

Without reform, it will rise to near three-quarters of all spending by 2040, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office has projected.

Because entitlement spending is outstripping revenue, the budget office anticipates, the federal debt will rise from 74 percent of economic output today to 100 percent in 2030, and then indefinitely from then on out, risking the possibility of a fiscal crisis.

Of course, those possibilities are far in the future, and government agencies don’t have a good track record of predicting events beyond a few years out.

But it’s not just the distant future at risk, said Douglas Holtz-Eakin, a Republican economist who now heads the American Action Forum, a conservative research organization.

Instead, the rising burden of those programs is already forcing Congress to cut spending on everything else, including basic research, infrastructure investments and defense.

The pressure created by rising entitlement spending is part of the reason that Congress, through the Budget Control Act hammered out between Obama and GOP leadership during the 2011 debt ceiling negotiations, imposed spending caps on defense spending and non-defense discretionary spending.

While defense hawks such as Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., have issued dire warnings about the security implications of the spending caps, appropriators and others have said that the caps on agency spending are unrealistic.

Budget experts don’t see tax increases as a solution to the problem, even if Trump were to consider tax hikes, rather than the monstrous tax cut he has campaigned on.

Consider one proposal to address the funding mismatch through taxes, namely lifting the cap on Social Security payroll taxes. Today, payroll taxes are capped at the first $118,500 of income. Lifting that so that all income was taxed would ensure that Social Security’s trust fund would be able to pay out all benefits through 2070, as opposed to through 2034 as is expected currently, according to the trustees.

But it also would be a trillion-dollar-plus tax hike over the next decade, beyond the outer limits of today’s politics. Bernie Sanders, the Vermont senator who challenged Clinton for the Democratic nomination as a liberal populist, stopped shy of that measure, proposing phasing in the payroll tax on incomes above $250,000.

So when a prospective President Trump gets a few years into his tenure and sees the deficit rising toward $1 trillion, he will be looking for spending-side reforms, some conservatives believe, and Ryan will be there to provide them.

“They’re going to have to do something,” Holtz-Eakin said. “Paul Ryan wants to do something and has ideas about what to do — that’s a good pairing.”

Ryan, for his part, said that he believed that, if it came to it, President Trump would sign congressional GOP legislation. (AP Photo)

“I now recognize that it’s a dangerous thing in D.C. to try to figure what people want to do, but it’s pretty easy to figure out what they have to do,” said Holtz-Eakin, who was director of the Congressional Budget Office and has advised Republican candidates. “And that often ends up being what happens, because Congress gets done what it has to and usually not much more.”

“President Obama has kicked the can down the road on entitlement and budget reform, and that’s going to impose, frankly, a budget disaster on the plate of the next president when he comes into office,” said Chris Edwards, a fiscal policy expert and the editor of the site Downsize the Federal Government that advocates spending cuts.

“Even if it was President Hillary Clinton, I think the budget disaster in the next few years is going to be so big that even she would move ahead with entitlement reforms,” Edwards said.

Yet the evidence suggests that, in the absence of a major, Greece-style crisis, Trump would have little interest in entitlement reform.

First 100 days

Trump’s priorities are building a wall along the Mexican border, reversing Obama’s immigration orders, imposing punitive taxes on companies that shift operations overseas and withdrawing from trade deals. Those are the points he has emphasized the most on the campaign trail and that he highlighted in a series of interviews with the New York Times discussing his goals for the first 100 days in office, when presidents typically accomplish their biggest legislative achievements.

Despite the perception that he is “malleable,” as Edwards called him, Trump has never indicated a willingness to pursue the Ryan-Romney agenda.

That’s not to say he’s not flexible. During his brief flirtation with a third-party presidential run in the 2000 election, Trump proposed a historic, one-time 14.5 percent tax on wealthy Americans, a soak-the-rich plan directly at odds with his current tax cut idea.

In the past, too, he has suggested raising the retirement age for Social Security, the memory of which gives liberal Social Security defenders pause about his current stance against cuts.

As a result, experts are left not knowing which of Trump’s promises to trust.

“Everything that he says that sounds pretty good to me I take with a grain of salt,” said Veronique de Rugy, a researcher at the libertarian Mercatus Center. “The stuff that he says that I don’t like at all somehow I really believe, based on his past.”

Instead of wishing that they can turn him into something he is not, Republicans could accept him as he is, hoping that the fiscal reckoning can simply be delayed while he’s in office. Such a capitulation would be a small price to pay to avoid a Clinton presidency, the thinking goes.

Republicans could hope that the fiscal reckoning can simply be delayed while Trump is in office — a small price to pay to avoid a Clinton presidency, the thinking goes. (AP Photo)

For conservatives “to espouse the same things we always have in spite of the world changing around us, I think, is not necessarily the right thing to do,” said John Campbell, a former California Republican member of Congress and ally of Ryan’s.

Campbell discouraged Republicans from seeking to win Trump over on the Ryan agenda, including support for Medicare, given that Trump has won the Republican primary with non-traditional voters. “You can have that conversation privately, but I don’t think in the middle of an election against an evil opponent such as Hillary Clinton is smart politics or good policy,” he said.

While Trump hasn’t changed the fiscal math facing the nation, Campbell acknowledged, there may be more headroom than conservatives generally think.

He pointed to the example of Japan, which has debt of about 240 percent of economic output — a fiscal burden nearly three times that of the U.S. Given that Japan has not suffered a debt crisis, it’s possible that the Treasury could issue far more debt without causing a problem.

Most fiscal experts, however, view the prospect of running up that amount of debt as an unconscionable risk. “There’s simply not going to be enough creditors and bondholders around to fund all this irresponsibility, so, no, I don’t think there’s any chance the United States could go the way of Japan and get up to that level of debt,” Edwards said.

Ryan’s gamble

Ryan, for his part, said that he believed that, if it came to it, President Trump would sign congressional GOP legislation. “I feel confident he would help us turn the ideas in this agenda into laws to help improve people’s lives,” Ryan wrote in the op-ed announcing his endorsement of Trump.

Ryan’s choice is a gamble that other Republicans are not willing to take, however.

Romney, Ryan’s running mate in 2012, said that his differences with Trump went too deep to be consoled by the fact that Trump might sign good legislation. “I’m not looking for Mr. Trump to change to a policy that more aligns with my own,” Romney said in an interview with CNN in June. “This is not a matter of just policy, it is a matter of character and integrity.”

Others simply don’t know whether to take Trump at his word that he would sign Republican House-passed legislation.

“The question is, is he going to sign it?” asked de Rugy. “I don’t know. I really don’t know.”