“The fact that Kafka the artist has played a distinctly subordinate role to Kafka the writer in our historical consciousness is attributable at least in part to our inadequate image of him,” argues Andreas Kilcher in his introduction to Franz Kafka: The Drawings. “In part” is carrying an awful lot of weight there. The more important reason is that Franz Kafka was an original, incisive, and disturbing writer and, well, not much of an artist.

Franz Kafka: The Drawings has troubled origins. Kafka’s art passed through many hands, several of which did not want to let it go. Kafka himself certainly had no desire for these drawings to see the light of day. Here they are, though, handsomely collected and buttressed by essays and information.

Would his drawings interest us if he had never written? May you be turned into a bug if you have the balls to claim the answer is “yes.” “They consist of just a few strokes,” writes Kilcher, “that do not show or tell but simply suggest.” OK, but was that by choice or by necessity? I see no reason to believe that he was capable of more. Judith Butler, in an essay on the drawings, preempts critics who might form “aesthetic judgements” that fail to perceive “their incomplete character as purposeful.” What do you think sounds more probable — that Kafka made rough sketches in the margins of his notebooks because he did not take them all that seriously or because he had some grand conceptual intention? Certainly, a copy of The Trial need not be supplemented by essays assuring us that it is valuable.

Still, given that we do know who Franz Kafka was, are his drawings interesting? I think so. First, Kilcher does prove that Kafka and his friends took his drawings somewhat seriously. For example, Max Brod — Kafka’s executor, who famously ignored his request that his works be burned after his death — recommended some of the drawings be used as cover art. Secondly, it is the case that the drawings reflect themes of Kafka’s literary work. Some are difficult to avoid calling Kafkaesque, such as one in which a man is being torn in half while a woman leans against a tree and watches him, stone-faced. You can bet it was deliberate that it is left ambiguous as to whether the man has had this fate inflicted on him or is inflicting it on himself. The woman does not care one way or the other.

A lot of Kafka’s figures, in their vague shapelessness, hint toward the author’s discomfort with the fleshiness of man. Their faces are blank. Their limbs are long, lean, and elastic. Butler is not wrong to observe how they almost appear to be in flight — transcending mere earthly forms. More prosaically, I wonder if their improbable movements reflect Kafka’s enthusiasm for calisthenics. (He used to exercise naked, believing in “the natural healing principle of nudity.”)

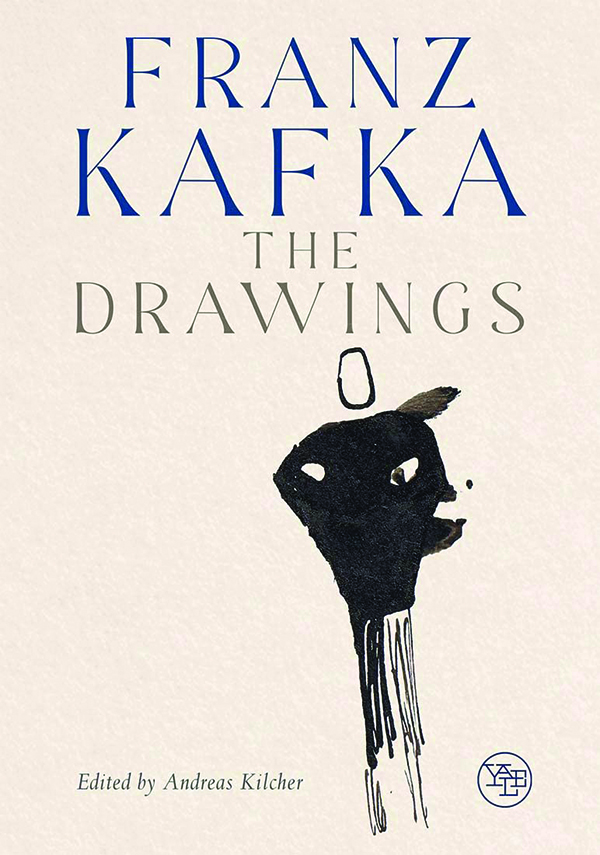

Note the eyes on the figures in this collection. Across face after face, they are either dark slits or wide, bulging, and buglike. Could he draw anything else? Maybe not. But one still appreciates the sense of paranoia they conjure up. See, for example, a haunting self-portrait that comes closer to justifying Butler’s “purposeful” claim than anything else here. See also a dark, bald figure in a tuxedo that looks as if he has strolled out of a nightmare. I imagine him as the deranged croupier of some dystopian casino.

Yet if one accepts that Kafka did not take all of these drawings especially seriously, some of them are more rather than less charming to the viewer. A drawing on a postcard of his sister eating lunch, for example, with her mouth open and her teeth on display cannot have been anything but mischievous — and it is touching to know Kafka could be mischievous, inasmuch as his sense for the perverse and the grotesque could be a source of play. A simple, pleasant sketch of a young woman, meanwhile, surprises us with its simple pleasantness.

We return to the novels and the short stories lest a great author be trivialized. “I am constantly trying to communicate something incommunicable,” Kafka once wrote to Milena Jesenska. “To explain something inexplicable, to tell about something I only feel in my bones and which can only be experienced in those bones.” There are hints of that in these drawings. But much less pierces the gap between his imagination and our comprehension than in the prose.

Still, the book provides intriguing and sincere insights into that imagination. It is not alive with genius, but it is haunted by its spirit — disturbing and amusing us with flashes of menace and mischief. You will not regret discovering Kafka’s stories before his sketches. But nor will you regret reading this book.

Ben Sixsmith is a writer living in Poland.