America’s founders have been under attack for the past several years. Some attacks have aimed at the principles for which those men stood, Enlightenment ideals about limited government and individual rights. Others focused on the men themselves, pointing out that many of these proponents of liberty were the owners of black slaves. In some critics’ minds, these flaws invalidate whatever good the founders did — a mindset that leads to the iconoclastic frenzy of statue destruction we saw in 2020.

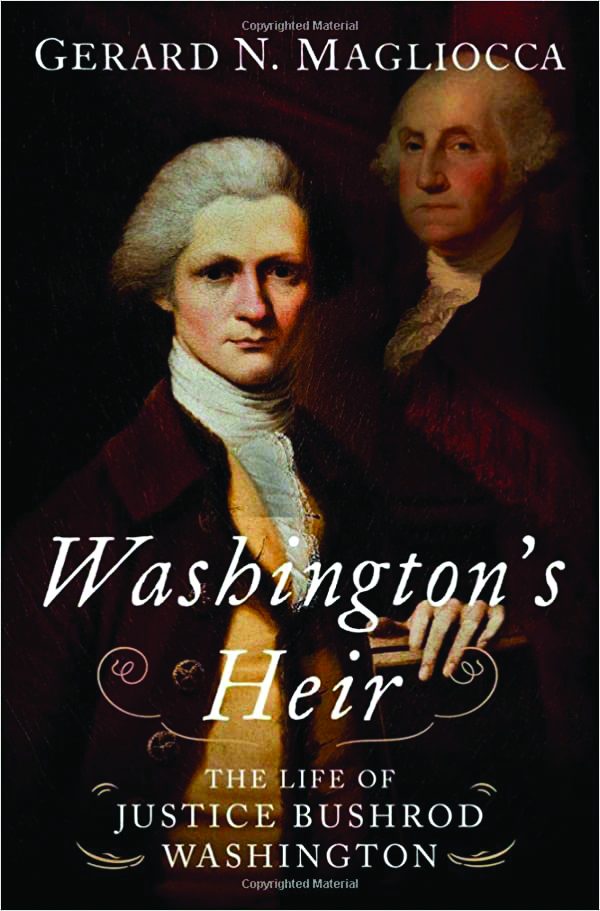

In Washington’s Heir: The Life of Justice Bushrod Washington, Gerard Magliocca gives one example of why such purity tests of historical figures must fail. In the first full-length biography of the long-serving Supreme Court justice, Magliocca details how Washington built up the power and prestige of the nascent federal government at a time when the effort was sorely needed while also laying the groundwork for what would decades later become a critical clause of the 14th Amendment. At the same time, the author does not paper over the justice’s lifelong ownership of slaves and his refusal to emancipate them even at his death.

George Washington, known as the father of his country, famously had no children of his own. But he did take an interest in his family, especially in Bushrod Washington, the son of his younger brother John. As the title suggests, Bushrod was not only George’s literal heir — he inherited Mount Vernon and more from his uncle in 1799 — but also his political heir. He, along with Chief Justice John Marshall, carried on the legacy of federalism even as Jeffersonian opponents swept to power in the elected branches of government in 1800 and after.

The political struggles between the Federalists and the Republicans, no relation to the current party of that name, were intense in this period, with many on both sides believing that their opponents’ victory would mean the end of the newborn nation. The conflict was as intense and vicious as any in the nation’s history outside the Civil War as a new polity worked to figure out the limits of partisanship in a republic.

In this arena of partisan vitriol, Bushrod played a reluctant part. After joining the legal profession, he focused more on law than politics, but the two are always intertwined, and as a member of a leading Virginia family, he was expected to play a role in the governance of his state. Still, when George Washington, then retired from the presidency, asked his nephew to run for Congress as a Federalist in 1798, he hesitated. Bushrod preferred to stay a private citizen and lawyer. But he accepted that duty, and his uncle, demanded more.

It must have come as a relief, then, when President John Adams nominated Bushrod to a seat on the Supreme Court later that year. He left the congressional race and began his service on the court that would be his home for the next 31 years.

He was joined by his friend Marshall in 1801, and the pair formed the nucleus of a court that would help define the limits of federal law for the new nation. The court in those days began to write joint opinions, contrary to the earlier English practice of having each justice write his own. This both helped to clarify the law and encouraged unanimity among the justices. And they were, for the most part, quite united, a group of Federalists holding back the tide of what they saw as radical Republicanism. Indeed, in the sparsely populated capital, the justices even lived together at the same rooming house, a practice Magliocca and others suggest contributed to the cohesion of the court even as new members, all Republicans, joined their number.

Unfortunately for historians, opinions that were mostly unanimous and mostly authored by Marshall leave many questions unanswered about what each justice really thought about the case and how those perspectives shaped the final product. But between Marshall and Washington, there may not have been much daylight — Magliocca quotes one fellow justice, William Johnson, as saying that the two were “commonly estimated as one judge.”

The life of a Supreme Court justice was very different in the early 19th century. Washington spent only a few months per year in the capital, and the high court issued very few opinions. Much of the rest of his time was spent “riding circuit.” In those days, there were no intermediate courts of appeal with their own judges as today. Instead, a Supreme Court justice would be assigned to a circuit where he would sit on a panel with a local district court judge. Poor roads and lodgings made the job arduous and kept many qualified lawyers from accepting the job in the first place.

It was on circuit that Washington wrote his most notable opinion in 1823, although at the time it was not seen as especially remarkable. In Corfield v. Coryell, Washington tried to define for the first time the meaning of the “privileges and immunities of citizens” as mentioned in Article 4 of the Constitution.

The words were not without some meaning in 1823 — as Randy Barnett and Evan Bernick noted in their 2021 book, The Original Meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment, the terms had been discussed in English and American law for decades. But in Corfield, Washington gave them their fullest explanation to that point, proposing just what sorts of rights Americans retained when they traveled outside their home states. Rather than requiring only that states treat citizens of other states equally, Washington’s opinion suggests that there are fundamental rights that “belong, of right, to the citizens of all free governments.”

What are these? While Washington admits that they “would perhaps be more tedious than difficult to enumerate,” he makes an effort, nonetheless. They include, he says, “protection by the government; the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the right to acquire and possess property of every kind, and to pursue and obtain happiness and safety,” along with the right to move to another state, to do business there, to use the courts, to hold property, and, most surprisingly, to enter “the elective franchise.”

The impact of this pronouncement was limited at the time, though abolitionist legal scholars incorporated it into their arguments for freedom. A generation later, the authors of the 14th Amendment looked for a standard of which rights ought to be secured for all Americans, including the newly freed slaves. Many, including the amendment’s principal author, John Bingham, settled on Corfield.

This was, Magliocca notes, “almost certainly not what Washington meant.” But intended or not, the principle expressed in Corfield became a part of the most sweeping constitutional change in favor of freedom and racial equality in American history. That it came from a Virginia plantation owner who was seemingly unconflicted about the institution of slavery does not change that fact: The idea matters more to history than the man. Washington, like his famous uncle, made strides for freedom that even he did not yet understand.

Kyle Sammin is editor-at-large at Broad + Liberty and the co-host of the Conservative Minds podcast. Follow him on Twitter at @KyleSammin.