Twenty-five years ago, the death of Stanley Kubrick was met with the sort of reaction that might today accompany the death of a president, pope, or pop star. On the night of March 7, 1999, Kubrick’s death at age 70 was the lead story on ABC’s World News Tonight, and the next morning, his obituary appeared on the front page of the New York Times. The Oscars, which took place a mere two weeks after the director’s demise, hastily assembled a tribute reel that was introduced by Steven Spielberg.

Even back then, there was something slightly specialized, even a little cultish, about the reverence with which Kubrick was treated. While Kurosawa, Bergman, and Ford each had at least a dozen or so agreed-upon masterpieces to their credit, the determinedly unprolific Kubrick built his legend on the backs of three pictures: Dr. Strangelove (1964), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and A Clockwork Orange (1971). Each is expressive and ambitious in various ways. But seen today, they seem fatally moored to their own era.

Dr. Strangelove was plainly a cry of Cold War-era anxieties; 2001, a curio from the time just after the arrival of space exploration and just before the ascendancy of “tune in, turn on, drop out” culture; and A Clockwork Orange, a horrid overindulgence in violence and sex suddenly made possible on the screen following the fall of the Production Code. But take away these films, and what remains?

After Clockwork, Kubrick deigned to direct just four more times. Ironically, Kubrick’s calculated elusiveness helps explain his otherwise unaccountable rise to prominence: Like J.D. Salinger, Kubrick swiftly established his brilliance with his early works, especially the crafty 1956 film noir The Killing. Wishing for that impression to remain fixed, he just as quickly made himself scarce. Kubrick thrived on the association of reclusiveness with genius.

Yet, in a critical error, Kubrick’s heirs have not propagated the Great One’s strategy. Instead, they have endorsed, or at least tolerated, countless exhibitions, retrospectives, DVD and Blu-ray releases, and even a documentary about the codes and symbols allegedly embedded in his 1980 horror movie The Shining. These things do not support the Kubrick legend as much as cause us to see it in a new light: Was this man really among the great movie artists, or was his eminence based on some odd alchemy of genuine talent, PR acumen, and strategic hermitage?

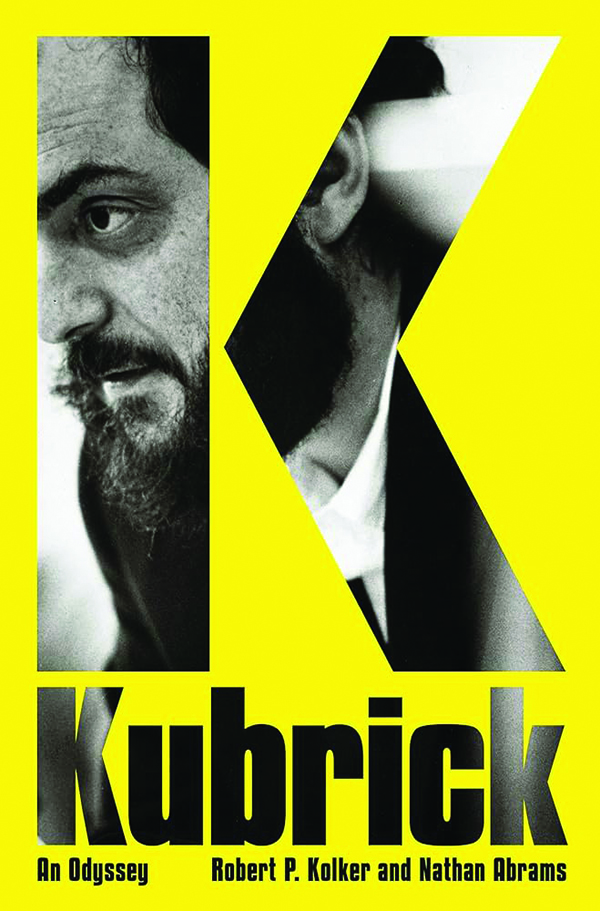

No brighter light has ever been cast on Kubrick than a new biography of unusual scope, detail, and insight by authors Robert P. Kolker and Nathan Abrams, devoted Kubrick scholars whose previous works include the definitive account of the making of the director’s final film, Eyes Wide Shut. He emerges illuminated but severely diminished. Surely that was not the intent of the project, but it is its outcome.

“The films he made from the outside and with such great toil stand as some of the most important, genuine works of honest art of the twentieth century,” the authors write admiringly near the end of a book whose meticulousness and perception goes some way toward proving the exact opposite. In this book’s account of how Kubrick lived, worked, and thought, he emerges smaller and less important. If this runs counter to the authors’ aims, so be it. It is still to their credit.

One of the enigmas of Kubrick’s career is what possessed him to turn to filmmaking in the first place and what further compelled him to pursue the trade with such undue fastidiousness; even amateur cinephiles are familiar with accounts of the director calling for punishing numbers of takes or becoming beholden to tiny details, including the color of lampshades. Obsession is a good thing in moviemaking, but most great directors have something personal that propels their obsession — Hitchcock and his fear of the police, for instance, or Hawks and his devotion to masculine friendship. But Kubrick’s films have no obvious wellspring beyond perfectionism as a virtue in and of itself.

Born to Jewish parents in the Bronx in 1928, Kubrick cottoned to photography early on, but even this formative interest is cast in peculiarly pedantic terms. “From the start I loved cameras,” Kubrick once said. “There is something almost sensuous about a beautiful piece of equipment.” This statement reverberates in subsequent accounts of the now-rich-and-successful, England-based filmmaker fanatically installing car phones (“He could use all that time wasted on the road to call lawyers, writers, and technicians”), satellite TVs, and the very best in early 1980s-era home computing. There is an inadvertently touching passage in which two Zeiss projectors are said by Kubrick’s assistant to be “the most precious objects that Stanley owned.”

Kolker and Abrams assiduously document Kubrick’s resourcefulness as he charted his life’s course: Without the benefit of a college education or a surplus of social skills, he went from landing photojournalism assignments in Look magazine to making documentary short subjects to directing a feature film, the lamentable, virtually unknown Fear and Desire (1952). But Kubrick’s turn to filmmaking is itself explained as a rather calculated matter, not one borne of deep personal convictions: “I sat there and I thought, well, I don’t know a goddamn thing about making movies, but I know I can make a film better than that.” And he could. But was it enough?

Far from being a genius-in-waiting, the young Kubrick sketched here comes across as a clever, resilient, and altogether ordinary young man of midcentury hipster-like tastes, an impression confirmed by a New York acquaintance from that time, Midge Decter: “We may imagine him in his youthful days as a bit of an intellectual, creative, dying to get out, positively drunk on the movies: a familiar figure.”

Not that there was anything familiar about Kubrick’s eventual cinematic style, which is, as described here, a study in glistening brilliance: the man knew how to shoot, stage, design, and market movies like no one else. Yet even Kubrick’s mature films might be most charitably described as aesthetic excellence in service to faddishness. Not one of his movies was fundamentally out of step with the times, including those once considered controversial. When risque, censorship-courting novelists like Henry Miller and William S. Burroughs were all the rage among the smart set, Kubrick set his mind on filming Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita; when horror movies started their gradual takeover of American popular culture, he labored on making the grandest of them all out of the slim pickings of Stephen King’s The Shining. Even Kolker and Abrams concede that Kubrick finally decided to plow ahead with Eyes Wide Shut — a project he had been contemplating for decades — because he saw a chance to exploit the early ’90s trend of erotic thrillers.

Of course, Kubrick cannot be faulted for having commercial instincts in show business, but he can be held to account for what now looks like stunningly unoriginal thinking. Again and again, the authors quote Kubrick’s statements about the motivations behind his movies, and again and again, his impulses and ideas are disappointingly earthbound and, in hindsight, lame. Dr. Strangelove, undoubtedly an appealingly anarchic film, was apparently borne of the director’s sincere yet insanely overstated terror of nuclear peril, which led him to strike up a friendship with On Thermonuclear War author Herman Kahn, and to seriously consider buying “an island in the Pacific to save him and his family.” At the time he was preparing 2001, Kubrick is said to have been exercised by fears of overpopulation (“Do you realize that in 2020 there will be no room on earth or all the people to stand?” Kubrick once asked, apparently straight-faced). Perhaps this fear of crowding led to the film’s cringingly hippie-dippie conclusion, in which all of humanity is reduced to a single “Star Child” hovering over Earth.

Nothing if not attuned to emerging trends, several of Kubrick’s late-in-life preoccupations resemble the neuroses of the young and the woke today. In the early 1990s, Kubrick expressed an almost religious confidence in the transformative potential of artificial intelligence; according to screenwriter Sara Maitland, Kubrick’s proposed film A.I. Artificial Intelligence reflected its maker’s conviction that robot children were the way of the future: “The film was intended to make us love them.” (The movie was later made, very effectively, by Steven Spielberg, and to its credit it did not inspire parents to trade in their flesh-and-blood offspring.) Incidentally, the story Kubrick told in A.I. assumes that major cities would soon flood due to global warming.

Kolker and Abrams establish that Kubrick savored family life, especially the children he raised, corralled, and pressed into service with his third wife and widow, Christiane. He was also nuts about dogs and cats. Even so, too many of Kubrick’s films are antagonistic toward the conventions of human civilization, a fact acknowledged by the co-screenwriter of The Shining, Diane Johnson: “Kubrick and I thought that The Shining was really about family hate.” That’s a legitimate topic for a movie, especially a horror movie, but Kubrick seemed to cater to the demonic father played by Jack Nicholson — to revel in his enmity toward his wife and his alienation from his son. By the same token, Full Metal Jacket wastes its chance to meaningfully reflect on the indoctrination of the young Marines through its gleeful presentation of the obscene tirades of the drill instructor. Even Kolker and Abrams admit that A Clockwork Orange is an unseemly muddle: the ultraviolent hero “is despicable, and we are asked to forgive him when it’s his turn to be the victim.”

Yet Kubrick often comes across as charming, personable, and sometimes rather pitiful; the account of his apprehension of doctors, and failing health during the making of Eyes Wide Shut, is touching because it reveals how easily a master can be felled. Yet, despite all of the quirks, idiosyncrasies, and foibles offered here, Kubrick still resembles a cipher — not unlike one of his favorite actors Peter Sellers, about whom Kubrick said this: “There is no such person.”

To their credit, however, Kolker and Abrams discern the outlines of a deeper, richer vision here and there in the Kubrick corpus. The filmmaker’s little-appreciated 18th-century drama Barry Lyndon (1975) is surely the only of his films that puts across a tragic view of life that seems deeply felt rather than endlessly intellectualized; one haunting scene of the title character’s little boy on his deathbed is, for the authors, one of Kubrick’s rare excursions into sentiment. And it’s the better for it.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Most intriguingly, the book documents one unmade Kubrick film in which he would have demanded more of himself than ever before: Aryan Papers, based on Louis Begley’s novel Wartime Lies, was a Holocaust story in which a Jewish boy and his aunt take on Catholic identities to make it through the war. This was almost Kubrick’s only project in which he would have directly engaged with his Jewish heritage. Officially, Kubrick tabled the movie because of the emergence of a contemporaneous rival production, Spielberg’s Schindler’s List, but his widow feels the director was simply overwrought and overwhelmed. “I will die from this,” Kubrick is supposed to have said, “and the actors will die, too, not to mention the audience.” Yet Kubrick’s recognition of this should have, as an artist, propelled him forward. His brother-in-law and producer Jan Harlan said: “If Kubrick was ever afraid of anything, it was to be carried away by those emotions.”

Instead, his legacy seems one of avoidance: of immersing himself in gadgetry and style, and of glibly inhabiting the hip sentiments of whichever era in which he was working. Kubrick must stand as a puzzlement. Here we have a rewarding biography of a filmmaker whose movies simply do not reward rewatching.

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.