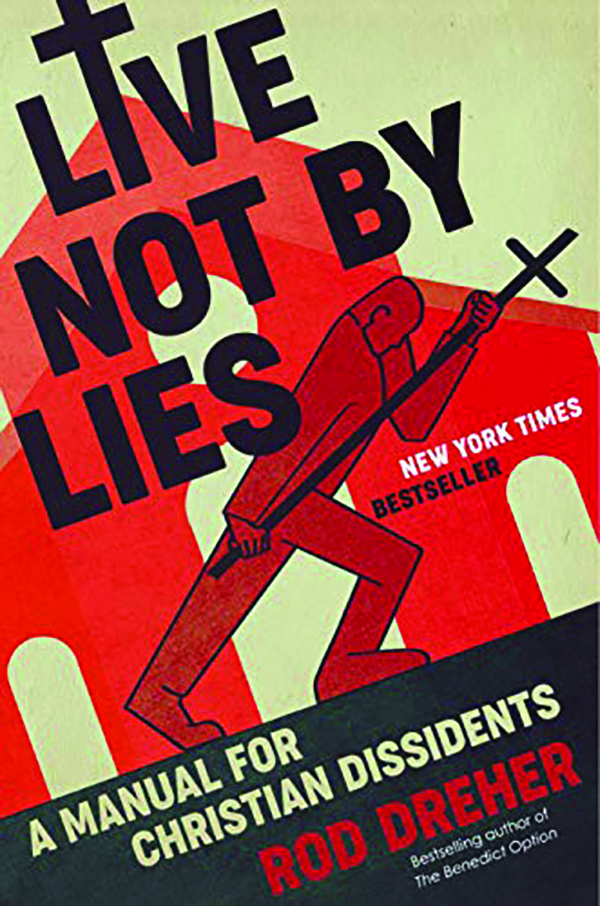

Political correctness is a religious movement led by a zealous vanguard who sees Christianity as its enemy. So argues Rod Dreher in his latest book, Live Not by Lies: A Manual For Christian Dissidents. Dreher claims that Christians persecuted by “soft totalitarianism” in the United States can find lessons in the struggles of anti-communist dissidents in the former Eastern bloc. Although his description of our current situation is in some ways accurate, Dreher’s comparison with Soviet and Eastern European communism disorients his analysis. His questionable appeals to history are matched with misinterpretations of thinkers such as Hannah Arendt. These two errors are useful for Dreher since they allow him to shirk the task of explaining what it is he wants to replace our current regime.

Ironically, Karl Marx, the villain of Dreher’s book, offered a famous warning against historical analogies in his “Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte.” Marx argued that in periods of crisis, bewildered people look to the past for precedents to apply to the novel problems of the present. For instance, many politicians in the French Revolutions looked to ancient Athens and Rome. But the example of these small, ancient city-states led the revolutionaries to misunderstand the challenge of their moment, which was to create a representative government for a modern nation-state with millions of inhabitants. By play-acting as Greeks and Romans, the French could pretend they merely had to return to the past rather than invent a new way of living together.

Dreher argues that wokeness, like Soviet-bloc communism, is a “form of government that combines political authoritarianism with an ideology that seeks to control all aspects of life.” But this analogy soon leads him astray. In Live Not by Lies, he suggests that wokeness, like the Marxist regimes of the 20th century, cannot endure because totalitarianism, “hard” or “soft,” will ultimately be broken on the anvil of “something harder: the truth.” Here, Dreher is too hopeful. The Soviet Union was destroyed by the contradictions of its economic and political structure, not by dissidents yearning for freedom. It is by no means clear that wokeness, which is only beginning its reign, faces the sorts of internal challenges that confronted the communists, who had to try to run modern economies without the help of markets. If wokeness does not contain the seeds of its own destruction, conservative Christians may be less like Soviet dissidents than like pagans of imperial Rome, watching their traditions die.

Dreher’s analogy to communism also obscures the distinctly American roots of wokeness and its socially conservative opposition, both of which are legacies of the 1960s. Two decades ago, Dreher tried to revive the hippie era’s Christian counterculture by pitting “Crunchy Cons,” conservatives who hold to values of solidarity and sustainability, against capitalism and mass culture. In fact, with his appeals to personal authenticity against a stifling mainstream, Dreher in Live Not by Lies sounds more like a hippie than Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. He demands the right to express a truth that defines his identity as an individual and as a member of a distinct community and to live out that truth in defiance of general social norms.

Like a member of a sexual minority facing legal and social persecution, Dreher insists on his right to “a life outside the mainstream, courageously defending the truth.” Christians have to go into the closet, retreating from the public square into their families and an archipelago of private institutions, such as “classical Christian schools.” Hiding from public scrutiny, getting such comfort as they can from alternative spaces and relationships, Christians should accept being “weird in society’s eyes.”

Christians ought to find this unappealing — who wants to live in a closet? But in Dreher’s view, they don’t have much choice. He believes that “old-fashioned liberalism,” which allowed groups with alternative visions of the good life to coexist thanks to its neutral legal frameworks and culture of respect for human dignity, is dead. Dreher does not seem sorry to see it go. Indeed, he suggests that classical liberalism is responsible for our woes. He attacks the way “liberals today deploy neutral-sounding” concepts such as “tolerance” to “disarm and ultimately defeat conservatives.” Moreover, he claims that liberalism, with its mission to emancipate humans from the bonds of traditional and religious authority, is the historical foundation for the totalitarian projects of Marxists and woke elites.

To make this dubious argument, Dreher appeals to Arendt, “the foremost scholar on totalitarianism.” He rightly notes that many of the factors that Arendt thought were behind the rise of 20th-century totalitarianism, such as social atomization and the decline of traditional authority, are present in the contemporary U.S. These conditions, Arendt argued, lead lonely, doubtful people to search for something to replace their former certainties. Here, Dreher argues, totalitarianism and wokeness appear as new “religions” that fill the void, giving people a narrative through which their lives become comprehensible.

Arendt, however, held that those who think they are making a critique of totalitarianism by calling it a religion misunderstand totalitarianism and insult religion. She did not see totalitarianism as offering a sense of meaning or community equivalent to those offered by traditional religions. Instead of liberating individuals from anomie, totalitarianism makes them even more isolated and fearful. Instead of gaining a narrative by which to make sense of life, people lose the basic condition necessary for doing so: a shared “world” of public discourse in which, by articulating their different views, they can work toward a new understanding that incorporates multiple perspectives.

More hopefully, Arendt believed that the breakdown of traditional forms of authority was an opportunity to return to the political wisdom of classical liberalism, which emphasized public reason over deference to revealed religious or ideological truths. In her 1970 Lectures on Kant’s Political Philosophy, Arendt offered a defense of liberal democracy based on vigorous, inclusive public debate. Only efforts to find common ground with those who do not share our views, she insisted, can give politics “truth.” The truths of logic (2+2=4) or science (discovered by experts) cannot answer our political questions, nor can truths held by a “sect” or minority that refuses to participate in the public sphere.

Woke ideology, by imposing its dogmas and silencing debate, is an enemy to the sort of truth Arendt saw as essential to politics. But Dreher’s truth is not Arendt’s. If Dreher is right, then the outlook is dire not only for conservative Christians but also for those who fear both religious and woke illiberalism. Dreher seems to imply that, given the failure of liberalism to create a world in which individuals can peacefully pursue truth, society requires some form of authoritarian collective belief to orient its members’ lives. While Dreher seems to be alarmed that woke discourse encourages people to “identify with groups” rather than as individuals, he cites Philip Rieff to claim that contemporary liberalism, with its “denial of any binding transcendent order,” is not only an unsustainable but a more “radical” violation of “the metaphysical order” than communism itself.

Ultimately, Dreher holds that Christianity, communism, and wokeness are functionally equivalent “competing religions” that offer believers the certainty of preestablished truth, protecting them from the disorientations of modernity and the challenges of debate. He perhaps means to indict only our new woke regime and not “old-fashioned” liberalism. But from within his premises, it is hard to imagine any defense of the latter. Old-fashioned liberals, those who do not wish to choose between any of the competing religions on offer, must offer a way out of this dilemma if their ideals are to survive.

Blake Smith is a Harper Schmidt fellow at the University of Chicago, where he works on cultural ties between France and India.