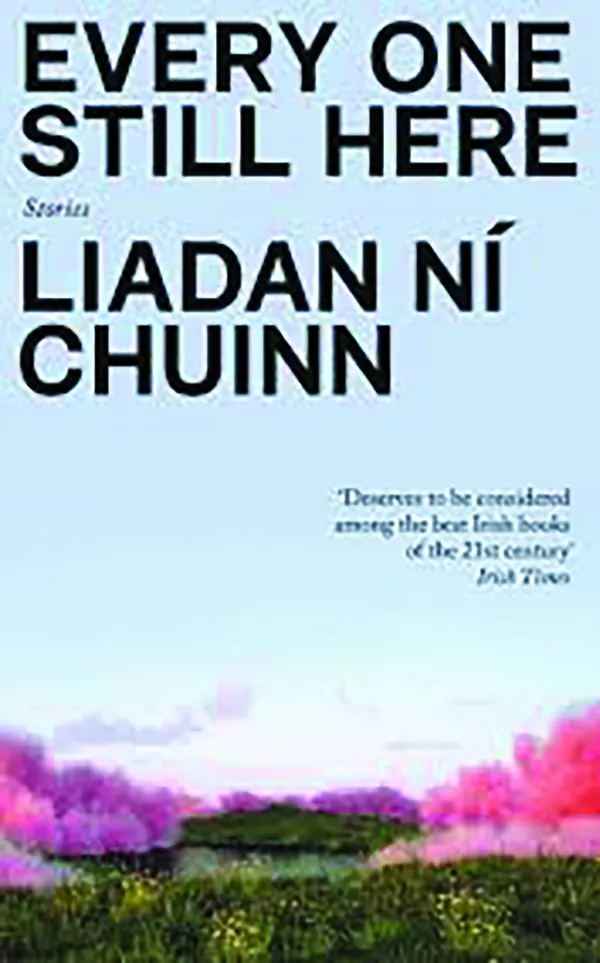

People have written numerous books about the Troubles between Britain and Ireland. Including, most recently, Philip Stephens’s These Divided Isles, in which he carefully explains the disturbing conflict. And while the Troubles form the background for Every One Still Here by Liadan Ní Chuinn, the six stories within the collection offer little explanation of the 30-year conflict. Instead, these narratives read like prose poems as they worm their way into the supposed consciousness of those who were born just as the conflict mostly ended. The stories are marked with molten anger and mystery.

The mystery even extends to the author’s identity. Liadan Ní Chuinn is a pseudonym, translated from the Irish as Grey Lady, Daughter of Wisdom. The stories suggest the author identifies as Catholic, as several characters take a Catholic perspective, and there are references to Catholic rituals, including the Mass, novenas, the cross of Saint Brigid on a car’s dashboard, as well as Catholic prayers and hymns. The author’s gender is not revealed. There is no picture of the author on the book jacket. All that is known is that Liadan Ní Chuinn was born in 1998, as the British-Irish War mostly ended.

The characters come from the first generation born after the Troubles. They are the sons and daughters of those who lived through the religious and political conflicts experienced in Northern Ireland from the late 1960s through to the late 1990s, culminating in the 1998 Good Friday peace agreement. They are young adults beginning their careers.

Several are planning to become writers. Others work in a museum where there are dead bodies and relics with no one to mourn them until an unknown visitor brings flowers to their display cases. Another character deals with hostility from a writing instructor as she tries to write about a mysterious girl on a bus. Still another plans to become a doctor and studies cadavers whose body parts remind him of casualties of the Troubles.

They see evidence of violence everywhere. One of the characters remembers what he’s heard about the Troubles and quotes Naomi Shihab Nye’s poem, “No Explosions”: “To enjoy fireworks/you would have to have lived/a different kind of life.”

In these stories, grown children remember a mother caring for an ill father, but they don’t remember what made the father ill. A grandmother remembers the difficulties she experienced during pregnancy. A nephew visits his uncle, who suffers from dementia and confuses his dog with his wife. The characters seem to have mental gaps that cannot be closed. They don’t understand each other, and this lack causes friction among them.

The stories often have a spiritual resonance. “Amalur,” for example, refers to the Basque myth that the Earth is the mother of plants and animals as well as the sun and the moon. Other stories recount mysterious circumstances. One person believes that she has died and the present world — in which everyone is living — is the afterlife

The writing style is generally engaging, although the storylines may be somewhat confusing to a U.S. audience, where the details of the Troubles are less known, and the contours of Irish English usage are less native than they are with what I suspect is the intended audience. (The book came out in Ireland and then England in 2025.) It’s not until the final pages that everything starts to make sense as the reality infusing the collection comes together.

“Daisy Hill,” the final story, is a page-turner. It begins as Rowan, the protagonist and an aspiring writer, visits his Uncle Jack, who has dementia. When Uncle Jack has an uncontrollable outburst of anger, Rowan takes him to the Daisy Hill Hospital emergency room and learns the hospital is filled with people also feeling uncontrollable anger. While they are waiting for a bed, Rowan remembers visiting an exhibition about the Troubles at the Ulster Museum. He looks at pictures of the exhibit on his phone and feels depressed, writing that men live with “bloodshotredeyedgrief….”

Soon, looking at photographs of people who were victims in the Troubles, Rowan’s “emotions spiral out and out.” He reads the paragraphs explaining the context of each picture and becomes enraged, believing that no one cares about these victims. This lack of concern is the point of these disquieting stories, with Rowan’s final words being ones of soul-piercing grief: “I would care if this were done to you.”

Ultimately, all the characters are grieving, but they don’t understand why. They are looking for a world where they can be themselves, ask questions, and hear answers. But they cannot find it, because that world no longer exists. In this world, everything is a lie, and they have been silenced, usually by people who love them and have the best of intentions.

Diane Scharper is a frequent contributor to the Washington Examiner. She teaches the Memoir Seminar for the Johns Hopkins University Osher Program.