More than six years after it first was signed into law, Obamacare has committed hundreds of billions of dollars to expand the number of Americans with some form of health insurance. But the program is in trouble. Enrollment is lower than expected, premiums are spiking, insurers are losing money — and in some cases, dropping out.

The next president will come into office facing an Obamacare crisis. The question is whether the response will be to further expand the role of government in healthcare, or to change course, and move the nation’s healthcare system in a more market oriented direction.

That the fate of the largest federal policy initiative in a half-century is tied to the financial performance of large corporations is the result of a concession to political reality made by President Obama. Rather than attempting to push a fully socialized healthcare system that would have drawn the ire of industry and proven more disruptive to the status quo, Obama got behind an approach that, as liberal New York Times columnist Paul Krugman put it, “basically relies on a combination of regulations and subsidies to rope, coddle, and nudge us into a rough approximation of a single-payer system.”

Under the public-private partnership that is Obamacare, individuals receive subsidies to purchase insurance that meets requirements established by regulators. Those requirements (such as mandating that insurers accept applicants with pre-existing conditions and offer certain established benefits) naturally drive up the price of insurance. But in theory, the carrot of the subsidies and the stick of the individual mandate were supposed to attract enough younger and healthier Americans into the market, to offset the cost of covering older and sicker Americans. It has not worked out that way in practice. In reality, there have been fewer overall enrollees to Obamacare than anticipated, and those who have enrolled have tended to have greater than expected medical expenses.

The Congressional Budget Office originally projected that by 2016, 21 million people would be purchasing insurance through one of Obamacare’s exchanges. But the actual number who signed up at the end of this year’s open enrollment period was 12.7 million, according to the Department of Health and Human Services. But this likely overstates it, because over the course of the year, a significant number of those people are likely to drop coverage or fail to keep up with the payments. In early 2015, for instance, HHS had initially reported 11.7 million people had signed up, but by September of last year, the agency announced that only 9.3 million were maintaining coverage.

The absolute number of enrollees is less important than the mix of enrollees — and there, too, the program has underperformed. Before Obamacare’s exchanges launched in 2014, administration officials had signaled that to succeed, the exchanges had to have roughly 40 percent of enrollees come from the 18 to 34 demographic. Yet the actual percentage has been around 28 percent.

To Sen. Bernie Sanders, Obamacare falls short because it relies too heavily on for-profit insurance companies. (AP Photo)

Though there’s some dispute over what the magic number would be, what’s indisputable is that insurers participating in Obamacare are losing tons of money, and are responding in a mix of ways: hiking premiums, decreasing access to doctors and hospitals, and/or exiting Obamacare altogether.

A recent analysis from healthcare information firm Avalere found that for 2017, insurers in nine state have proposed rates that would increase the cost of Obamacare’s mid-level plans by an average of 16 percent, with increases ranging from five percent in Washington state to an average of 44 percent in Vermont. This comes on top of increases in the previous several years, bringing the monthly cost of insurance plans for 50 year-old male nonsmokers in Vermont to $685.

UnitedHealth, the nation’s largest insurer, announced in April it was exiting most Obamacare markets, but not before it expects to lose nearly $1 billion during its short-lived participation in the program. Other major insurers that are losing money on Obamacare have thus far said that they planned to stick with the program, but they are still losing money. It’s unlikely that investors will tolerate a money-losing venture forever, so unless Obamacare stabilizes, more insurers are likely to follow United’s lead.

Compounding the problem is that when insurers exit, it means that there are fewer insurers around to share the enrollees with high medical expenses, in addition to less competition, and worse choices for consumers – all of which can contribute to further increases in premiums. And when costs increase, it becomes harder to attract a healthy pool of enrollees, because younger and healthier individuals are most likely to feel that they can go without insurance if the price soars. That, in turn, only makes it more difficult for existing insurers to make a profit. Next year, insurers will be facing another obstacle, because two of the three programs within Obamacare that were established to help insurers absorb risk and losses will expire at the end of 2016.

This is the reality that will be facing the next president when he or she is sworn in on Jan. 20.

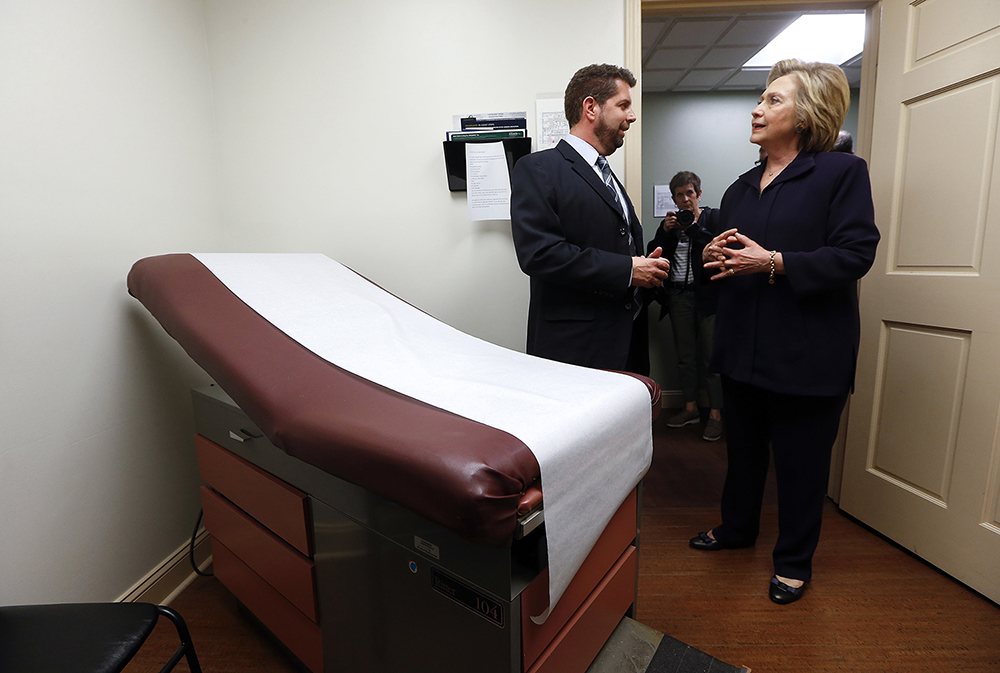

During the Democratic primary season, the debate over healthcare was emblematic of the larger argument between Hillary Clinton and Sen. Bernie Sanders over whether to pursue incremental progress on the liberal agenda, or push radical change. To Sanders, Obamacare falls short because it relies too heavily on for-profit insurance companies. He has argued for replacing that model with a European-style single-payer healthcare system. Clinton, in contrast, responded that pursuing such an idea would endanger the progress made by Obamacare, which she said she wanted to “build on.” For instance, she wants to expand subsidies to help individuals with the cost of insurance and out-of-pocket expenses. The bottom line is the debate on the Democratic side is not about whether to reform Obamacare to reduce government interference, but over how much more to expand government’s role in healthcare and how quickly it can or should be done.

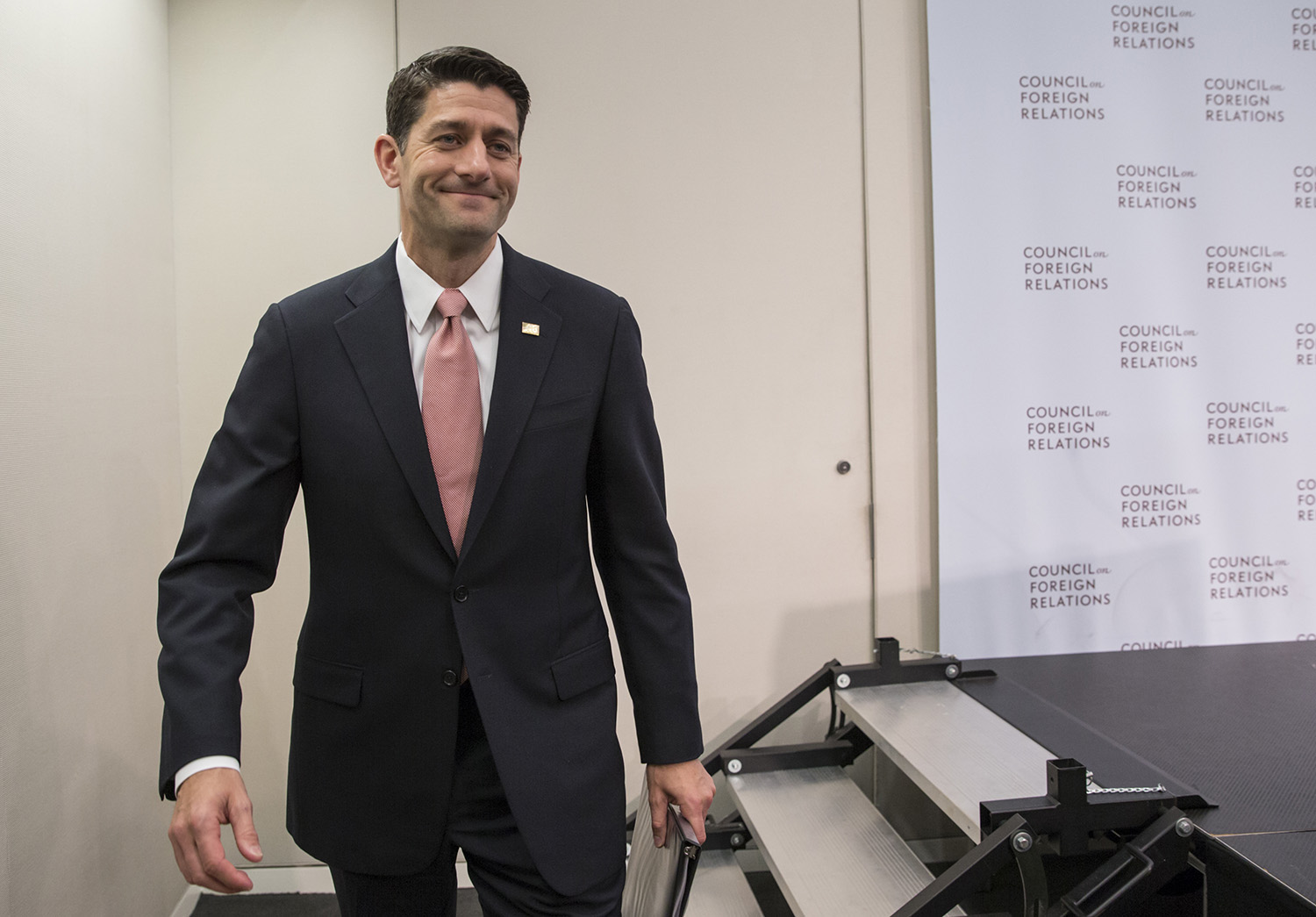

House Speaker Paul Ryan has vowed to introduce a healthcare plan as part of his project to provide Republicans with policies to run on. (AP Photo)

On the Republican side, the matter is less clear. Though there have been a number of plans released on healthcare among opponents of Obamacare, Republicans have yet to unify around a single one. This election year, House Speaker Paul Ryan, R-Wis, has vowed to introduce a healthcare plan as part of his project to provide Republicans with policies to run on. Donald Trump has also offered some bullet points of a plan, but given that he has made a number of contradictory statements on the subject of healthcare (at various points in the campaign he’s called for repealing Obamacare and has also praised single-payer healthcare systems), it’s a guessing game as to what policy he’d pursue as president.

Generally speaking, conservative healthcare plans aim at making the U.S. healthcare system function more like other markets in the American economy. That is, in most other industries, Americans are accustomed to seeing costs go down and quality improve over time with technology. This has been the case, for instance, with computers, televisions, and telecommunications. But the opposite has happened with healthcare.

The reason is that unlike other markets, when it comes to healthcare, consumers have very little control over how they spend their money, little knowledge of how much goods and services cost, and barely any choice. Nearly all Americans get their healthcare either from government or their employers (who maybe offer them a choice among a few plans). Because they are shielded from costs, they have less incentive to shop around for better prices or say no to any unnecessary spending.

Though such problems existed before Obamacare went into effect, the program’s raft of taxes, regulations, and government spending erected more barriers to the creation of a real free market. Despite its unpopularity, should Republicans find themselves in power in 2017, they will be looking at a program that has been on the books for years and that has been providing coverage for millions of individuals through an expanded Medicaid and the insurance exchanges. So the debate among Obamacare’s critics in the health policy world has been over how much of the law can realistically be undone given that wiping it out would now disrupt many Americans’ health insurance arrangements.

There is a spectrum of opinion on the right about how to usher in a more patient-centered system, but most conservative and libertarian policy experts agree that it will require a mix of tax and regulatory reforms.

Under the current system, insurance benefits are exempt from taxation if purchased through one’s employer, but anybody who purchases insurance on their own must do so with after-tax dollars. The fact that the system is rigged in favor of employer-based insurance not only is unfair to the millions of Americans who are self employed, but it also creates less flexibility, as individuals can’t keep the same insurance when they move from job to job.

Most plans offered as alternatives to Obamacare seek to address this discrimination in the tax code, as there is no way of creating a consumer market if individuals don’t have control over their own healthcare dollars. However, plans differ on how aggressively they are willing to disrupt employer-based health insurance, which is how roughly half of Americans obtain their coverage. Some would fully replace the employer-tax advantage with a standard deduction for all individuals, while others would merely seek to cap the employer benefit, and instead offer fixed-sum tax credits that can be used toward the purchase of insurance.

Hillary Clinton wants to expand healthcare subsidies to help individuals with the cost of insurance and out-of-pocket expenses. (AP Photo)

Another feature of Obamacare alternatives are proposals to expand health savings accounts, which allow individuals to put aside money on a tax-free basis to pay for medical expenses.

In addition to the tax component, market-based reforms seek to strip the regulations placed on the sale of insurance specifying the type of plans that insurers must offer, which would reduce the price of coverage and allow companies to offer a broader range of policies to meet different individuals’ medical needs.

One of the most popular aspects of Obamacare is the ban it placed on denying coverage to those with pre-existing conditions, and that will be among the most politically difficult pieces of Obamacare to unravel. This issue could be addressed by setting up subsidized purchasing pools at the state level that focus on covering people with such conditions.

In the healthcare outline Trump released during the primary season, he did embrace many of the popular reforms advocated by free market policy experts. But the plan also included a number of puzzling elements. For instance, it proposed allowing insurers to sell coverage across state lines, which has been one way that reformers have proposed getting around benefit mandates imposed at the state level. But the plan introduces a major caveat: “As long as the plan purchased complies with state requirements, any vendor ought to be able to offer insurance in any state.” The whole point of removing state barriers is so that individuals in highly regulated states with expensive insurance can have the option of buying cheaper insurance in states with fewer regulations. So, the caveat in the Trump plan introduces — that all plans have to meet in-state regulations anyway — effectively negates the whole purpose of that reform.

In addition to endorsing some free market reforms, however, Trump has also said that he supported a universal healthcare system in which government paid for everybody to be covered. He has also called for having the federal government directly negotiate drug prices through the Medicare program, an idea long favored by liberals, and one also being championed by Clinton.

Ryan has in the past pushed Obamacare alternatives based around giving individuals tax credits toward the purchase of insurance. In endorsing Trump, he argued that he saw the presumptive nominee as somebody who could advance the GOP agenda. Healthcare would be the first major test.